I don’t understand why this record is so overlooked. Perhaps it’s because at the time of its release, when every other 1960s folkie was busy going electric in the wake of Liege and Lief, Bert — ever the nonconformist — chose to go the other direction. This is nearly all-acoustic, and it might be his most gentle and heartbreakingly sad record ever. There’s a dreamy, hazy vibe to much of the music — one of the tracks is even titled “A Dream, A Dream, A Dream” — that creates a timeless feel; by which I mean not that the music hasn’t dated (although it hasn’t), but that it actually seems to stop time. I don’t think Jansch ever topped his vocal on “Tell Me What is True Love”, and it goes without saying that his guitar playing is superb. Seek it out. Fun Fact: Psych-folk supergroup Espers did the title track on their covers album The Weed Tree. –Brad

I don’t understand why this record is so overlooked. Perhaps it’s because at the time of its release, when every other 1960s folkie was busy going electric in the wake of Liege and Lief, Bert — ever the nonconformist — chose to go the other direction. This is nearly all-acoustic, and it might be his most gentle and heartbreakingly sad record ever. There’s a dreamy, hazy vibe to much of the music — one of the tracks is even titled “A Dream, A Dream, A Dream” — that creates a timeless feel; by which I mean not that the music hasn’t dated (although it hasn’t), but that it actually seems to stop time. I don’t think Jansch ever topped his vocal on “Tell Me What is True Love”, and it goes without saying that his guitar playing is superb. Seek it out. Fun Fact: Psych-folk supergroup Espers did the title track on their covers album The Weed Tree. –Brad

Folk

Lindisfarne “Fog On the Tyne” (1971)

This album came along in the States at a time when groups like Sandy Denny, Fairport Convention, Strawbs, Nick Drake and a bunch of others were plying the waters of Celtic folk rock. But Alan Hull & Company were different; these guys were as ragged as Fairport in their loosest moments — but they could be as polished and sharp as the Strawbs in their best moments. These guys were tight, multi-instrumentalists that played in the best of the tradition of English folk bands of the late 60’s and early 70’s. Steeleye Span, Jethro Tull and Gryphon were also contemporaries of Lindisfarne and had nothing on these guys. If you like any of the bands mentioned here and you’ve never added any Lindisfarne to your collection, you are missing a real treat here. Fog On the Tyne is Lindisfarne’s best effort overall (though many of their albums are very good) and their combination of rich, instrumental passages is backed by thick and bawdy harmonies in a very British and rollicking sensibility. The band’s guitar, mandolin and a seeming hundred other stringed instrument attack — along with a great rythym section on the bass and drums — gives them a sound that holds up well even today, thirty years later. Sadly, I heard somewhere that Alan Hull passed away recently, so there will be no nostalgia tours or “here we are again” releases from Lindisfarne. Get this one. It’s simply great. —R. Lindeboom

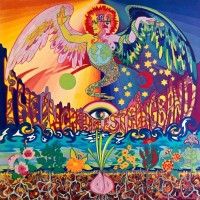

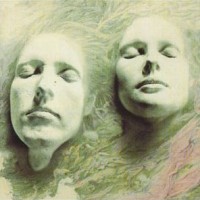

Incredible String Band “The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion” (1967)

The second ISB album, regarded by many as a peak moment in the evolution of the British psychedelic underground. Following the release of the band’s trio debut in the summer of 1966, Clive Palmer had split for Afghanistan, Robin Williamson had taken his girlfriend, Licorice McKechnie, to Morocco for an open-ended stay, and Mike Heron had opted to stay in Edinburgh. Heron returned to playing rock music, but in late 1966, Williamson came back from Marrakesh, bearing a wealth of strange North African musical instruments, and an equal number of compositional ideas.

Before long, the two had reformed the ISB as a duo, and they soon began woodshedding in a rural Scottish cottage. Joe Boyd, who had produced the first LP, had started a new club in London called the UFO, in partnership with John “Hoppy” Hopkins (the founder of The International Times). Boyd felt the scene was boiling over and was convinced the ISB had their part to play. He visited the pair, suggesting he become their manager and that they record a second album. The sessions for The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion happened at John Wood’s London studio in late spring 1967, and featured the lovely bass work of Danny Thompson (who had joined Pentangle two months earlier), the vocals of Licorice, and guest spots for “Hoppy”’s piano and Nazir Jairazbhoy’s sitar.

The album was released to great fanfare in July, 1967, just as the ISB was returning from an appearance at the Newport Folk Festival. With its uber-psych cover art by Dutch design firm The Fool (then being envied for their work with The Beatles), and classic songs (traditional folk, swathed in kaftans, incense and finger cymbals), 5000 Layers was truly a record for its time. Hailed by everyone from John Peel to Paul McCartney, the album went to Number One on the UK folk charts, and was an omnipresent accessory in every student garret. Four-plus decades on, it remains one of the all-time readymade classics of the ‘60s. —Forced Exposure

The Antiquarian Ear:

A Guide to the British Folk Renaissance

The evolution of folk music in Britain and America in the early to mid-20th century can be viewed as two essentially parallel lines. In both increasingly mechanistic and bureaucratic societies, listeners connected with folk as a more authentic musical expression of being and as a link to the cultures to which their countries’ rapid modernization was laying waste . In late 50’s Britain, it could even be argued that American folk and blues eclipsed that of the British strain in popularity. Indeed, the British Invasion of the following decade could never have been mounted had it not been for skiffle, a hybrid of blues, folk, country, and other indigenous American musical forms embraced by millions of British teenagers—including four certain ones from Liverpool.

But by the late-60’s these two paths would dramatically diverge. Many British musicians began to look less westward and further inward by “getting it together in the country” and seeking solace and inspiration in the myths, folklore, and landscapes of “Albion”, a storied antiquarian world that occupied the collective consciousness of many Britons and whose history stretched back to ancient times. This aesthetic would come to define one of modern Britain’s most fertile musical movements. Peaking in the early 70’s, it passionately and reverently embraced the traditions, heritage, and culture of a much older Britain while doing so with restless, forward-thinking imagination and experimentation. Recently, this movement was finally given the scholarly treatment it deserves in Rob Young’s excellent book, Electric Eden. It’s a must-read for anyone wishing to traverse this mythic soundscape. A few of these definitive selections will also help you begin the odyssey, from which you may never return:

Bert Jansch Jack Orion (1966). With just a guitar, a banjo, his voice, and occasional musical accompaniment from friend and fellow British folk icon John Renbourne, Jansch (who passed away this past autumn) made it clear the endless possibilities inherent in this newly realized version of British folk. Melding traditional Anglo and Celtic musical forms with blues and jazz sensibilities, Jansch laid the template for much of what would come out of Britain over the next few years. Highlights include the title track, a re-imagining of the “Glasgerion” ballad, and a similar reworking of another canonical ballad, “Blackwaterside”, this version of which Jimmy Page would shamelessly pilfer for his own “Black Mountain Side”, which appeared on Led Zeppelin’s 1968 debut.

Bert Jansch Jack Orion (1966). With just a guitar, a banjo, his voice, and occasional musical accompaniment from friend and fellow British folk icon John Renbourne, Jansch (who passed away this past autumn) made it clear the endless possibilities inherent in this newly realized version of British folk. Melding traditional Anglo and Celtic musical forms with blues and jazz sensibilities, Jansch laid the template for much of what would come out of Britain over the next few years. Highlights include the title track, a re-imagining of the “Glasgerion” ballad, and a similar reworking of another canonical ballad, “Blackwaterside”, this version of which Jimmy Page would shamelessly pilfer for his own “Black Mountain Side”, which appeared on Led Zeppelin’s 1968 debut.

The Pentangle The Pentangle (1968). This LP marks the first in a string of stunning releases by Britain’s first true “supergroup” comprised of guitarists Bert Jansch and John Renbourne, bassist Danny Thompson, drummer Terry Cox, and vocalist Jacqui MacShee. Their ethereal sound owed just as much to jazz as it did to folk, causing many to refer to it as “folk-jazz”. Whatever categorizations one wants to throw at the Pentangle are ultimately meaningless. Nothing before or since has ever sounded like them, and this album is where it all began.

The Pentangle The Pentangle (1968). This LP marks the first in a string of stunning releases by Britain’s first true “supergroup” comprised of guitarists Bert Jansch and John Renbourne, bassist Danny Thompson, drummer Terry Cox, and vocalist Jacqui MacShee. Their ethereal sound owed just as much to jazz as it did to folk, causing many to refer to it as “folk-jazz”. Whatever categorizations one wants to throw at the Pentangle are ultimately meaningless. Nothing before or since has ever sounded like them, and this album is where it all began.

The Incredible String Band The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter (1968). The ISB’s third album does not receive as many accolades as their second, The 5000 Spirits or Layers of an Onion [read our review], but in terms of adventurousness, risk-taking, and sheer other-worldliness, in the British folk canon The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter is almost without peer. Flush from the success of the aforementioned second LP, members Mike Heron and Robin Williamson utilized complex multi-tracking recording techniques and a large assortment of exotic acoustic and electric instruments to create this unforgettable psych-folk classic. Its centerpiece, the 13+ minutes “A Very Cellular Song”, is a spiritual freeform freakout that combines a Bahamian lullaby with a Sikh hymn, and it just might be their finest achievement. Another huge influence on Zep, Robert Plant has often cited it as the primary field manual consulted during the making of Led Zeppelin III.

The Incredible String Band The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter (1968). The ISB’s third album does not receive as many accolades as their second, The 5000 Spirits or Layers of an Onion [read our review], but in terms of adventurousness, risk-taking, and sheer other-worldliness, in the British folk canon The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter is almost without peer. Flush from the success of the aforementioned second LP, members Mike Heron and Robin Williamson utilized complex multi-tracking recording techniques and a large assortment of exotic acoustic and electric instruments to create this unforgettable psych-folk classic. Its centerpiece, the 13+ minutes “A Very Cellular Song”, is a spiritual freeform freakout that combines a Bahamian lullaby with a Sikh hymn, and it just might be their finest achievement. Another huge influence on Zep, Robert Plant has often cited it as the primary field manual consulted during the making of Led Zeppelin III.

Nick Drake Five Leaves Left (1969). Appearing from out of nowhere on the London folk club circuit in the mid-60s, Drake quickly caught the ear of producer Joe Boyd (perhaps British folk’s most important major player), after which the singer would be booked into London’s Sound Technique Studios to record this debut. Drake’s tragic personal and music career trajectory is now well-known, and the problems that plagued the production and release of this LP were not outside of this narrative. At odds with Boyd from the beginning regarding many of the songs’ backing arrangements, the strings that ended up on the final cut nevertheless compliment Drake’s lyrics and fretwork perfectly, particularly on the majestic “River Man”. What’s also striking is how confident and assured he still managed to sound here, every bit as melancholy and intense as ever but less damaged and defeated than he often sounded in his later work.

Nick Drake Five Leaves Left (1969). Appearing from out of nowhere on the London folk club circuit in the mid-60s, Drake quickly caught the ear of producer Joe Boyd (perhaps British folk’s most important major player), after which the singer would be booked into London’s Sound Technique Studios to record this debut. Drake’s tragic personal and music career trajectory is now well-known, and the problems that plagued the production and release of this LP were not outside of this narrative. At odds with Boyd from the beginning regarding many of the songs’ backing arrangements, the strings that ended up on the final cut nevertheless compliment Drake’s lyrics and fretwork perfectly, particularly on the majestic “River Man”. What’s also striking is how confident and assured he still managed to sound here, every bit as melancholy and intense as ever but less damaged and defeated than he often sounded in his later work.

Fairport Convention Liege and Lief (1969). Also produced by Joe Boyd, the Fairport’s fourth release followed Unhalfbricking [read our review], the typical favorite of aficionados. But ultimately, Liege and Lief remains the band’s most important contribution to British folk. A magnificently paradoxical work, all the songs here are traditional ballads, reels, or jigs featuring Sandy Denny’s angelic vocals soaring above distorted amplified instruments. This would be the last album that Denny recorded with the band, next joining Fotheringay [read our review] for their sole 1970 release, which also holds a rightful place in the British folk canon.

Fairport Convention Liege and Lief (1969). Also produced by Joe Boyd, the Fairport’s fourth release followed Unhalfbricking [read our review], the typical favorite of aficionados. But ultimately, Liege and Lief remains the band’s most important contribution to British folk. A magnificently paradoxical work, all the songs here are traditional ballads, reels, or jigs featuring Sandy Denny’s angelic vocals soaring above distorted amplified instruments. This would be the last album that Denny recorded with the band, next joining Fotheringay [read our review] for their sole 1970 release, which also holds a rightful place in the British folk canon.

Vashti Bunyan Just Another Diamond Day (1970). Among British folk’s diverse cast of eccentric characters, Vashti Bunyan has one of the most fascinating stories. Following a failed late-60s attempt at establishing herself as a female pop star a la Marianne Faithful, Bunyan and her boyfriend embarked on a trek across Britain in a horse-drawn wagon, eventually settling on a remote farm in the Outer Hebrides. Shortly thereafter, Joe Boyd (surprise!) coaxed her back into the studio to record this LP. Bunyan’s travels obviously gave her a lot of material to work with here, and her connection to the rugged, windswept Scottish landscape can be felt in songs like “Hebridean Sun”, “Rose Hip November”, and “Rainbow River”. Released in 1970, the record sold very few copies and promptly vanished into obscurity. Bunyan then left the music business and moved to Ireland to raise a family and continue her agrarian existence, presumably to be never heard from again. Meanwhile, the album grew in stature over the following decades, its original pressing becoming a big ticket collector’s piece and its songs becoming a huge influence on some American indie folk artists, most notably Davandra Banhart and Joanna Newsome. This renewed interest in Bunyan’s work lead to a loving reissue of this essential album, and the recording of a new one in 2005, Lookaftering, which was almost as good.

Vashti Bunyan Just Another Diamond Day (1970). Among British folk’s diverse cast of eccentric characters, Vashti Bunyan has one of the most fascinating stories. Following a failed late-60s attempt at establishing herself as a female pop star a la Marianne Faithful, Bunyan and her boyfriend embarked on a trek across Britain in a horse-drawn wagon, eventually settling on a remote farm in the Outer Hebrides. Shortly thereafter, Joe Boyd (surprise!) coaxed her back into the studio to record this LP. Bunyan’s travels obviously gave her a lot of material to work with here, and her connection to the rugged, windswept Scottish landscape can be felt in songs like “Hebridean Sun”, “Rose Hip November”, and “Rainbow River”. Released in 1970, the record sold very few copies and promptly vanished into obscurity. Bunyan then left the music business and moved to Ireland to raise a family and continue her agrarian existence, presumably to be never heard from again. Meanwhile, the album grew in stature over the following decades, its original pressing becoming a big ticket collector’s piece and its songs becoming a huge influence on some American indie folk artists, most notably Davandra Banhart and Joanna Newsome. This renewed interest in Bunyan’s work lead to a loving reissue of this essential album, and the recording of a new one in 2005, Lookaftering, which was almost as good.

Steeleye Span Please to See the King (1971). A band with more than a passing resemblance to Fairport Convention (female lead vocalist, electrified arrangements of traditional material—it also didn’t hurt that founding member Ashley Hutchings was a previous member of the Fairports), Steeleye Span would prove to be one of British folk’s most enduring acts. Ironically, they lacked a drummer, but oftentimes they rocked harder than many bands who had one. This second album saw the arrival of Martin Carthy, an already huge presence on the British folk scene. Here he by no means hogs the spotlight, and his stellar guitar playing and supporting vocals make a perfect foil for lead vocalist Maddy Prior. This was the best lineup of Steleye Span, but it unfortunately lasted for only two more albums, neither of them nearly as good as this one.

Steeleye Span Please to See the King (1971). A band with more than a passing resemblance to Fairport Convention (female lead vocalist, electrified arrangements of traditional material—it also didn’t hurt that founding member Ashley Hutchings was a previous member of the Fairports), Steeleye Span would prove to be one of British folk’s most enduring acts. Ironically, they lacked a drummer, but oftentimes they rocked harder than many bands who had one. This second album saw the arrival of Martin Carthy, an already huge presence on the British folk scene. Here he by no means hogs the spotlight, and his stellar guitar playing and supporting vocals make a perfect foil for lead vocalist Maddy Prior. This was the best lineup of Steleye Span, but it unfortunately lasted for only two more albums, neither of them nearly as good as this one.

The Strawbs From the Witchwood (1971). By the time of this release, the Strawbs had been around for a while, their earliest incarnation being more of a straight folk act (which briefly counted future Fairports’ vocalist Sandy Denny as a member). But over time they gravitated more towards a folk-rock sound, and with the addition of keyboardist Rick Wakeman here the band moved further into prog territory, a blessing or a curse depending on your personal tastes. Despite its studio wizardry and modern instrumentation, the Strawbs maintain a strong psychic connection to their homeland’s past. There are many fine moments here, including the daydreamy “Flight”. But the LP’s most memorable track is its side 1 closer, “The Hangman and the Papist”, a tragic tale of betrayal and injustice that could only have emerged from one of the darker chapters of Britain’s history.

The Strawbs From the Witchwood (1971). By the time of this release, the Strawbs had been around for a while, their earliest incarnation being more of a straight folk act (which briefly counted future Fairports’ vocalist Sandy Denny as a member). But over time they gravitated more towards a folk-rock sound, and with the addition of keyboardist Rick Wakeman here the band moved further into prog territory, a blessing or a curse depending on your personal tastes. Despite its studio wizardry and modern instrumentation, the Strawbs maintain a strong psychic connection to their homeland’s past. There are many fine moments here, including the daydreamy “Flight”. But the LP’s most memorable track is its side 1 closer, “The Hangman and the Papist”, a tragic tale of betrayal and injustice that could only have emerged from one of the darker chapters of Britain’s history.

Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band No Roses (1971). This record represents a fruitful collaboration between another established folk icon, Shirley Collins, and a band that could have been called “Fairport Span” since many members of the Fairports (includiing Richard Thompson) and Steeleye Span participated in its recording. Actually, by the time of the album’s final mix, over 27 musicians had logged in time in the studio. Yet the record still retains a strong focus and clarity of purpose. The raucous “Murder of Maria Martin” illustrates what the Velvet Underground and Nico might have sounded like had it been recorded in the Scottish Highlands rather than New York.

Shirley Collins and the Albion Country Band No Roses (1971). This record represents a fruitful collaboration between another established folk icon, Shirley Collins, and a band that could have been called “Fairport Span” since many members of the Fairports (includiing Richard Thompson) and Steeleye Span participated in its recording. Actually, by the time of the album’s final mix, over 27 musicians had logged in time in the studio. Yet the record still retains a strong focus and clarity of purpose. The raucous “Murder of Maria Martin” illustrates what the Velvet Underground and Nico might have sounded like had it been recorded in the Scottish Highlands rather than New York.

Richard and Linda Thompson I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight (1974). After Thompson’s first solo outing, 1973’s Henry the Human Fly, singer Linda Peters, to whom he had recently married, joined him for his second outing, which would unexpectedly become the high watermark of his career. Almost everything about this record stands in stark contrast to the Utopian ideals that largely characterized the British folk movement in its earlier days, from its disturbing minimalist cover to the no-frills (mostly electric) guitar, drum, and bass arrangements . The lyrical content is much more personal than mythical or historical, and it often conveys a sense of loneliness, loss, and failure. Even some of the more upbeat material, like the title track, shows an abandonment of the country life and an embracing of an urban one. The deeply cynical “The End of the Rainbow” in a way serves as a fitting epitaph for a movement nearing its end.

Richard and Linda Thompson I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight (1974). After Thompson’s first solo outing, 1973’s Henry the Human Fly, singer Linda Peters, to whom he had recently married, joined him for his second outing, which would unexpectedly become the high watermark of his career. Almost everything about this record stands in stark contrast to the Utopian ideals that largely characterized the British folk movement in its earlier days, from its disturbing minimalist cover to the no-frills (mostly electric) guitar, drum, and bass arrangements . The lyrical content is much more personal than mythical or historical, and it often conveys a sense of loneliness, loss, and failure. Even some of the more upbeat material, like the title track, shows an abandonment of the country life and an embracing of an urban one. The deeply cynical “The End of the Rainbow” in a way serves as a fitting epitaph for a movement nearing its end.

Further Listening: At least a brief mention should be made about Ireland’s folk scene of this period. On many levels it can be difficult to distinguish it from that of Britain’s, as most Irish artists of merit ended up working in London (or, as was the case with the Clancy Brothers, New York). But one group who never got its due was Sweeney’s Men, a Galway-based trio whose sound embodied a beguiling mix of traditional Irish folk, eastern influences, and psychedelia. They only released two proper albums during their existence, which are nearly impossible to find. Fortunately, Castle Records released a wonderful anthology in 2004, Legend of Sweeney’s Men, which collects almost everything they ever recorded

For all intents and purposes, the arrival of punk rock in the late ’70s killed off what was left of the British folk movement. Many folk artists, including the ones listed above, adapted to the changing times successfully, but very few recorded anything as significant as the landmark LPs of their pasts. A high-profile revival—a British equivalent of the American alt-country movement of the early ’90s—never really materialized, which now seems strange. Yet today, bands like Mumford and Sons hint that such an event might be on the horizon. Who knows? Maybe a new generation of musicians will one day return to Albion and draw inspiration from it in ways that are just as new and exciting as those of their elders. To quote Nick Drake, “Time will tell us.” —Richard P

Are we forgetting your favorite late-60’s or 70’s British Folk or Folk-Rock LP? Leave your suggestions in the comments field below:

Shelleyan Orphan “Helleborine” (1987)

Shelleyan Orphan are one of those peculiar little groups that show up once in a while, make some stunning music, and then disappear. They have no peers, so trying to describe who they sound like is impossible. They are etherial, and never more so than on their first album “Helleborine,” a stunning mix of orchestral sweetness and lyrical mastery. Long before their demise into songs with titles like “Dead Cat,” the Orphans were writing songs like “Epitaph Ivy and Woe,” juxtaposing the generally sweet and upbeat timbre of the music with the often graphic lyrics describing a cemetery and a charnel house. On “Anatomy of Love,” vocalist Caroline Crawley asks the same questions that anyone that is in love asks: “Does it still move you? Does it still make you feel that?” “Cavalry of Cloud,” with it’s gorgeous introduction, will give you chills. “Helleborine,” the album’s only instrumental track, is another example of the artistic beauty the Orphans had a complete mastery of. This was their supreme moment, and when they began their fall, they would fall far. —Eric

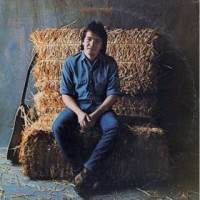

John Prine “John Prine” (1971)

People who don’t listen to country music much tend to consider John Prine a country artist, it seems, while people who do listen to country music consider him a folk artist. I guess non-country fans are taken by how country-sounding this music is; and I guess country fans are taken by how un-country these lyrics are. This could be called country music in retrospect, but Nashville didn’t put up with songs that deal with the subjects Prine wrote about. Still doesn’t, in fact.

Some singer-songwriters of this era wrote both funny songs and serious songs. Jim Croce did it. So did Prine’s pal Steve Goodman. And Jimmy Buffett. But Prine was different–he somehow blended his humor together with his more serious sentiments, rather than separating “funny” songs from “serious” ones. It’s uncanny, really.

For instance, “Illegal Smile” is completely goofy, but its message–that marijuana is fun and makes him happy and should be legal–is crystal clear. “Sam Stone” is a devastating depiction of a drug-addicted vet who unravels after the war, yet Prine makes it subtly funny the way only he could. Is there a better, funnier way to describe a junkie parent from a child’s perspective than the line, “There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes”? Just about all these songs make you laugh but also make a point or at least tell a good story. —Rocket88

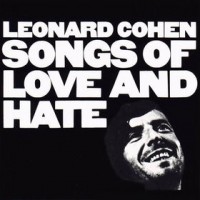

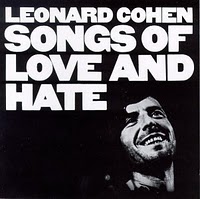

Leonard Cohen “Songs of Love and Hate” (1971)

This albums is absolutely bone-chilling and perfect for peripatetic journeys through dark nights. The biggest drawback of prolific wordsmiths like Dylan and Cohen is the acute degree of attention they necessitate and compel. “Avalanche” begins with a sinister broken chord and Cohen’s famous growl/murmur, more disturbing than the confessional howls of Kurt Cobain, more bleak than the sassy, impudent yelp of Johnny Rotten, more numinous than the transcendental whimpers of the Buckleys, Elliott Smith, & co. “Diamonds in the Mine” sees Cohen delving into unfamiliar territory, as the typically monotonous raconteur approaches the drunken, bluesy passion of Tom Waits and Captain Beefheart, imposed over a queerly saccharine chorus. Always an asset, the backing female choir is never eerier than in “Dress Rehearsal Rag.”

Remarkably, Cohen crafts not only stories but songs, not only songs but tunes, which at their best evoke the timelessness of Dylan’s. Although to label anything Cohen has written as “catchy” or, even more absurdly, “singable,” would probably discredit this review, “Dress Rehearsal Rag” and “Love Calls You by Your Name” feature conspicuous choruses, while the opening lines “Avalanche” refuses to leave you, and “Diamonds in the Mine” not only permits but invites a sing-a-long. —Garrett

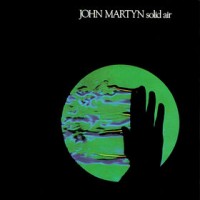

John Martyn “Solid Air” (1973)

Solid Air is an amazingly effective amalgamation of blues, folk, and jazz. Though I can’t think of any album that sounds similar musically, Solid Air reminds me of Astral Weeks because it creates an emotion that is entirely its own. The title track drew me in; Martyn uses his voice like an instrument so it melts into the saxophone part, creating a totally unique sound. The album continued to be a mesmerizing listening experience and it shows off Martyn’s handle of a wide variety of musical styles. “Over The Hill” and “May You Never” are folk masterpieces, the former highlighted by Richard Thompson’s fabulous mandolin performance and the latter with its unforgettable melody. “I’d Rather Be The Devil” and “Dreams By The Sea” are both exciting, menacing tracks that show off Martyn’s skills on electric guitar with his impressive command of the Echoplex guitar effect. The former builds in tension and then crashes down into a peaceful musical section that ends the song on a serene note. The latter recreates some of the jazzy atmosphere of the title track with another fantastic saxophone part. “Don’t Want To Know,” “Go Down Easy” and “Man In The Station” are mellow but engaging folk tracks where the combination of Martyn’s voice and the tinkling instrumental parts are quite soothing. “The Easy Blues” shows Martyn’s strengths as an acoustic blues performer and the album closes on an uplifting, peaceful note with “Gentle Blues.” The album is so consistent, it is impossible for me to pick favorites. It simply deserves five stars. —Nathan

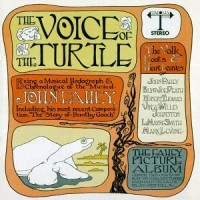

John Fahey “The Voice of the Turtle” (1968)

Like some of John Fahey’s other projects in the ’60s, this was actually recorded and assembled over a few years, and primarily composed of duets with various other artists (including overdubs with his own pseudonym, “Blind Joe Death”). One of his more obscure early efforts, Voice of the Turtle is both able and wildly eclectic, going from scratchy emulations of early blues 78s and country fiddle tunes to haunting guitar-flute combinations and eerie ragas. “A Raga Called Pat, Part III” and “Part IV” is a particularly ambitious piece, its disquieting swooping slide and brief bits of electronic white noise reverb veering into experimental psychedelia. Most of this is pretty traditional and acoustic in tone, however, though it has the undercurrent of dark, uneasy tension that gives much of Fahey’s ’60s material its intriguing combination of meditation and restlessness. —Richie Ubermench

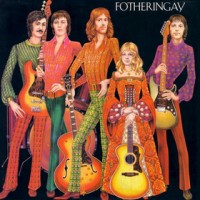

Fotheringay “Fotheringay” (1970)

After her successful and excellent beginnings with Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny carries on surprising us with new gems with Fotheringay. Unfortunately this new band will officially release only one album and Sandy will carry on in a solo career. The 3 masterpieces are first the haunting and emotional “Banks of the Nile” another thrilling war song with delicate acoustic accompaniment and very soulful singing. “Winter Winds” is also an absolute folk beauty backed by a wonderful acoustic riff between each verse.

At last, the opener “Nothing More” is the 3rd Sandy Denny gem here. “The Sea” is another very attaching song also sung by Sandy. Among the songs songs not sung by her, “Peace in the End” and “The Way I Feel” are 2 other wonders. The first one has pleasant backing vocals while the second one has a haunting guitars backing and medieval melody in a fast tempo. There is not a single mediocre song here. This album is truly a must-have if you are into folk, folk-rock music. —Paul

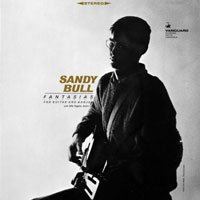

Sandy Bull “Fantasias for Guitar & Banjo” (1963)

The face of folk music changed forever when Sandy Bull blended folk with jazz and Indian music on his otherworldly debut. He was years ahead of his time: in 1963 rock and folk music meant simple, three-minute songs while he was composing long, progressive, improvised jams. Bull also played nearly every instrument on the record and was an early adopter of using tapes while playing live. In “Blend” Bull and Ornette Coleman drummer Billy Higgins create a massive, supreme folk suite, with elements of traditional western and eastern music and American primitivism was born. “Carmina Burana Fantasy” is an interpretation of a classical piece (prog-rock?). “Gospel Tune” was folk with electric guitar two years before Bob Dylan plugged in. “Little Maggie” is simple song for guitar and banjo. Everything is instrumental, monumental, and open-minded. Nearly fifty years later, Fantasias for Guitar & Banjo still sounds like music from another world. –Zielona

Leonard Cohen “Songs of Love and Hate” (1971)

Never the most chipper of performers, Cohen seems to have stopped taking his happy pills here, but the album is all the better for it as far as I’m concerned. Songs about religion? Check. Anguish? Check. Love? Check. No sex though..must be his impotent period. But anyway, it’s just fabulous from start to finish, and contains some of his best lyrics, especially “Avalanche”, “Famous Blue Raincoat”, and “Diamonds In The Mine”. The latter track finds him nearly losing it like some angry lounge singer, his background vocalists barely keeping him in check. There was never any doubt Leonard Cohen was a poet, but both his written word and music shine perfectly in unison here. Speaking of poetry, if you’re a woman in college right now and some smooth character is shooting you provocative looks from the poetry section in the library, run like hell. I know he’s probably holding a copy of Cohen’s “Beautiful Losers” and has a wine collection, but he’s not worth it. Trust me. –Neal

Never the most chipper of performers, Cohen seems to have stopped taking his happy pills here, but the album is all the better for it as far as I’m concerned. Songs about religion? Check. Anguish? Check. Love? Check. No sex though..must be his impotent period. But anyway, it’s just fabulous from start to finish, and contains some of his best lyrics, especially “Avalanche”, “Famous Blue Raincoat”, and “Diamonds In The Mine”. The latter track finds him nearly losing it like some angry lounge singer, his background vocalists barely keeping him in check. There was never any doubt Leonard Cohen was a poet, but both his written word and music shine perfectly in unison here. Speaking of poetry, if you’re a woman in college right now and some smooth character is shooting you provocative looks from the poetry section in the library, run like hell. I know he’s probably holding a copy of Cohen’s “Beautiful Losers” and has a wine collection, but he’s not worth it. Trust me. –Neal