If you know Weather Report primarily from their latter-day funk-groove thang, this may come as a surprise — perhaps even a pleasant one. For one thing, Joe Zawinul is restricted mostly to organ and piano, with none of the synthesizer excess of later albums. The balance between Zawinul and Wayne Shorter, too, is much more even (and Shorter’s “Eurydice” is my favourite piece on the record). With bassist Miroslav Vitous on acoustic instruments, the album may remind you of Miles Davis’s In A Silent Way, on which, of course, Zawinul and Shorter played crucial parts. There’s a kind of calm and serenity hanging over the music, even when the playing gets furious (which, with these guys involved, it often does). “Orange Lady” was also recorded by Miles Davis as “Great Expectations” (for which he cheekily took the composition credit). –Brad

If you know Weather Report primarily from their latter-day funk-groove thang, this may come as a surprise — perhaps even a pleasant one. For one thing, Joe Zawinul is restricted mostly to organ and piano, with none of the synthesizer excess of later albums. The balance between Zawinul and Wayne Shorter, too, is much more even (and Shorter’s “Eurydice” is my favourite piece on the record). With bassist Miroslav Vitous on acoustic instruments, the album may remind you of Miles Davis’s In A Silent Way, on which, of course, Zawinul and Shorter played crucial parts. There’s a kind of calm and serenity hanging over the music, even when the playing gets furious (which, with these guys involved, it often does). “Orange Lady” was also recorded by Miles Davis as “Great Expectations” (for which he cheekily took the composition credit). –Brad

Jazz

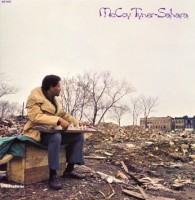

McCoy Tyner “Sahara” (1972)

Tyner recorded prolifically for Milestone throughout the 1970s, and produced a number of fine recordings. “Sahara” might be the best. It represents the state of the art for the time of its release, 1972.

The greatest strength of this recording lies in its varied aural landscape. If you want Tyner’s signature thunderous chords and lightning right-hand runs, cue up “Ebony Queen” and “Rebirth.” Need some spiritually rich solo piano? Move to “A Prayer for My Family.” Then try the 23-minute title track, which has his reedman, Sonny Fortune, playing flute, his bassist, Calvin Hill, playing reeds, and the group joining drummer Alphonse Mouzon with various percussion effects. As far from a blowing session as you can get, this extended performance is a well-planned trip across a variety of endlessly fascinating terrains. As if all this isn’t enough, on “Valley of Life,” Tyner picks up a kyoto, a Japanese stringed instrument and produces a delicate impressionistic sketch, aided by Fortune, again on flute.

“Sahara” represents the best that jazz had to offer in the early ’70s. The musicians aren’t afraid to display their chops (Fortune adds blazing soprano and alto sax to his delicate work on flute), but Tyner clearly is intent on finding new territory and expanding the definition of jazz, and he succeeds brilliantly. —Tyler

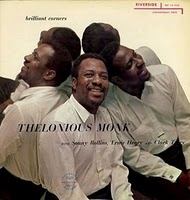

Thelonious Monk “Brilliant Corners” (1957)

With four of the five selections here being originals, Brilliant Corners displays the pianist’s obsession with knotty, jagged melodies that leap around in unpredictable ways, be it on the segmented, abrasive title track, the obviously bluesy “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” the ragged ballad “Pannonica,” which features Monk simultaneously playing a bell-like celeste and piano, and the bold bounce of “Bemsha Swing.” The sidemen, including Sonny Rollins, settle in to the compositions admirably, taking inspiration from Monk’s idiosyncratic approach, and there’s a sense of freedom in their solos despite the songs’ atypical nature. A great example of one of the most original voices in classic jazz. –Ben

With four of the five selections here being originals, Brilliant Corners displays the pianist’s obsession with knotty, jagged melodies that leap around in unpredictable ways, be it on the segmented, abrasive title track, the obviously bluesy “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” the ragged ballad “Pannonica,” which features Monk simultaneously playing a bell-like celeste and piano, and the bold bounce of “Bemsha Swing.” The sidemen, including Sonny Rollins, settle in to the compositions admirably, taking inspiration from Monk’s idiosyncratic approach, and there’s a sense of freedom in their solos despite the songs’ atypical nature. A great example of one of the most original voices in classic jazz. –Ben

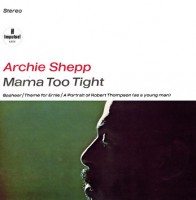

Archie Shepp “Mama Too Tight” (1966)

“Mama Too Tight” is an album whose original vinyl sides served as a proper division– the first side is among the most difficult to digest, but like many of the more complex free jazz works, bears rewards with repeated listens, the second side is much more accessible, moving through moods on the three different tunes. What makes this record difficult is the odd instrumentation– Shepp blows his tenor, and adds to this clarinet (Perry Robinson), trumpet (Tommy Turrentine), two trombones (Grachan Moncur III and Roswell Rudd), tuba (the mighty Howard Johnson, and a pianoless rhythm section (bassist Charlie Haden and drummer Beaver Harris). This unusual instrumentation is partially responsible for the difficulty in digesting the material on “Mama Too Tight”.

In particular, on the first side, “A Portrait of Rober Thompson (as a young man)”. While it feels like free improv, there appears to be a highly concrete structure, as Shepp states, restates, and exposes various themes (mostly gospel, march and swing influenced) throughout the piece. But it is tough, because it feels at times like an incoherent mess. Patience is the key to this one– early on, the more conventionally structured second side will be soothing in comparison. Over time, the piece will come to make sense, but patience and repeated focused listening will be required.

The second side is definitely more conventional, “Mama Too Tight” is a funky blowout, Mingus-like in its voicing and gospel-tinged hard bop styling, with some stunning soloing on the part of all the musicians involved. Like Mingus’ gospel-oriented work, this is just a lot of fun, a great great song, and actually is one of the most straightforward pieces on any early Shepp record– only his solo shows any real signs of the “Fire Music” sound. The ballad, “Theme for Ernie”, played passionately by Shepp with brass support voiced in an orchestral fashion, shwocases the leader’s ability to invoke mood and emotion through his playing. Shepp’s tone is thin and airy and has a plea of pain in it– this is really among the most beautiful work he’s ever done. “Basheer”, continuing the thread of more conventional sounds, has a big band does the blues feel to it– the playing is somewhat more “out” than the previous two, and once again, Shepp just wails away. its a really interesting piece.

Overall, this is a really great album, and probably a good jumping in point for Shepp’s work– it can be a bit difficult at first, but there’s a lot of great material here and its well worth the listen. —Michael

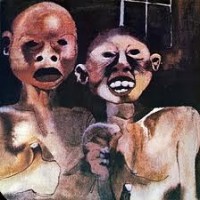

Masekela “Home Is Where the Music Is” (1972)

Hugh Masekela is one of the more colorful characters in jazz and has done numerous things in the course of his career, some of which, especially his forays into pop music, have caused critics to sneer at him; however, when he entered a studio in London with fellow South Africans Dudu Phukwana and Makhaya Ntshoko and the Americans Larry Willis and Eddie Gomez in 1972, the result was an unqualified and an undisputed success.

Home Is Where the Music Is is a fusion album in the best sense of the word, because it fuses only the most successful elements to arrive at a whole that is much larger than its parts. Masekela and main composer/producer Caiphus Semenya draw from traditional South African music, American jazz, soul and funk with a dash of spiritual jazz, and thanks to an ensemble in which each musician is no less than outstanding, the result is a thouroughly engaging, deeply soulful album that captivates the listener from the very first moment.

Masekela is clearly at the top of his game here; the range of tonal colors that he produces on his flügelhorn is remarkable, his use of half-valve tones and slurs impressive; at times you almost expect the valves to pop out of the horn. Phukwana is no second; while probably not quite as quick-fingered, he is firmly in the groove, and when he digs in, you want to follow him down every inch.

The fusion movement may have produced numerous misguided albums, expressing confusion rather than fusion, but Home Is Where the Music Is is one of the best examples of the genre. —Brian

Jackie McLean “Destination Out!” (1964)

Based on the title, I was expecting some blistering, fast-paced jazz, probably dominated by squalling saxophone and so on. For those of you who have listened to Destination Out! already, you will know that I found this not to be the case. Perhaps I should have taken more heed of the exclaimation mark, because in many ways I can draw similarities between what Jackie does here and what Eric Dolphy was doing on Out To Lunch! Admittedly, this tends not to have the skronkier qualities of that album, but firstly, the replacement of piano with vibes is obvious, and then there’s the combination of weird, staggering music that’s somehow also really accessible and exuberantly fun to listen to. This is often cited as a pretty essential jazz album, especially in the context of post/hard bop, and honestly, I can really say it is. There are few albums which really nail experimentation and accessibility at the same time, but the sophisticated and restrained, often atmospheric playing on Destination Out! means that even with the odd rhythms and wonderfully wonky playing this is still a pleasure to listen to over and over again. A classic. —Timmay

Dave Holland “Conference of the Birds” (1972)

This is not an ordinary record in any respect. Free jazz and the 1960s avant-garde had ironically generated its own conventions. Conference of the Birds ignores them and sets up its own outstanding performance standards for both individual voices and ensemble. The compositions are all Holland’s, inspired by the dawn chorus outside his flat in London in the early summer mornings.

The first theme, “Four Winds” is a delightful opener, marked by Holland’s characteristic firm, precise fingering. The bass immediately sets the atmosphere of the record: a light, free dance of notes. Holland’s bouncing fingering sharply contrasts with Barry Altschul’s fizzing cymbals. Sam Rivers and Anthony Braxton converse almost indistinguishably, politely exchanging commentary. On “Q & A” Altschul converses with himself, quietly alerting his companions, who gradually make their appearance with little interjections. These fragments progressively accumulate to form a kind of dance of free individuals, like birds pecking at grain, each jumping according to its own whim, chasing its morsel. Then, the title-tune, “Conference of the Birds”; It’s one of the great compositions of jazz, perhaps the most distinctive and memorable 1970s original (in retrospect, an accolade it should probably share with Weather Report’s “Birdland”, released four years later). It is a delicate, contemplative song to beauty and quietude, both melancholy and uplifting, evocative of both aching loneliness and the intimacy of companionship. Holland’s double bass figure must be one of his most celebrated. Altschul’s marimba is divine in its simplicity, accompanied by the plain, unadorned flutes of Braxton and Rivers. “Conference of the Birds” is almost like the calm before the storm – the track that follows it, “Interception”, is a wild, intense vehicle for each soloist to give free rein to his passions. This is followed by “Now Here (Nowhere)”, the most spacious of all six pieces. It offers a cautious reconciliation to dissenting voices after “Interception”, underscored with the ubiquitous bass. Holland cultivates a tone here honed into a ovoid, sculpted sound with a hint of vibrato. Finally, on “See-Saw”, we have Altschul again creating a effervescent ambience to a blistering Rivers solo. This is the final climax to an awesome, astonishing album, one of the great classics of the post-free era. —Ricard

Quincy Jones “Walking In Space” (1969)

After a few year period of releasing film scores in the mid sixties, Jones entered the studio and recorded Walking in Space (1969); an electric/acoustic/ jazz/funk/big band record produced by his friend, the great Creed Taylor of CTI records. With jazz luminaries Roland Kirk, Freddie Hubbard and Ray Brown (and a few other heavy hitters of the time), Jones conducts, arranges, and rearranges a handful of tunes from the stage along with some standards.

Side one is made up of two tracks from the Broadway hit “Hair” (Dead End, Walking In Space) funked up with swagger and velvet shag. The record begins with Ray Brown’s walking bass settin’ it along with some electric piano chiming it up and rim shots galore- some muted trumpet and flute phrases establish a simmering melody, then the brass section enters along with some electric guitar jabbing from Eric Gale. The title track begins similarly; Hubbard breaths more muted sounds from his horn while Roland Kirk’s tenor slithers around it only this time it lasts a bit longer as a female vocal section sneaks in giving the track a swanky lounge vibe. As the tempo increases, Hubert Laws cuts through with a whispery flute solo eventually giving way to some muscular statements from Eric Gale and Roland Kirk- a standout number.

Side two begins with a cool rendition of Benny Goldson’s “Killer Joe” (some feel this is thee rendition). Hubbard blows his muted trumpet over a medium sized brass section with some understated guitar fills throughout, more sexy vocals come in and sing the chorus – imagine if Ellington’s orchestra were to cover Miles’ “So What” with a plugged in rhythm section and the backup singers from Sergio Mendes’ Brazil ’66-you get the idea. Another highlight is from Toots Theilmans, who shows up with harmonica in hand for a fractured and somewhat abstract harmonica solo on one track (I Never Told You). The Album closes with an eighteenth century gospel standard (Oh Happy Day). A gospel choir sings the chorus while Hubert Laws answers the vocal phrases with his flute; you also get the rarity to hear Ray Brown really get down on electric bass on this cut.

Jones created some probing instrumental music on Walking In Space. Supported by a cast of stellar musicians-from the grooves to the smooth backbeats it was an absolute perfect fit for Taylor’s slick productions and definitely one of the strongest records in the CTI catalog. – ECM Tim

Miles Davis “Agharta” (1975)

Agharta is a ferocious animal, not one to be afraid of, but a beast of darkness nevertheless. It is not the hole inside which Miles Davis disappeared for five years briefly after it was released, it is rather the culmination of everything he worked towards ever since the release of Bitches Brew. As much a group effort as most of the albums of his “electric” phase, Miles is joined here by Sonny Fortune on saxophones and flute, and the two are embedded in the relentless twin guitars of Pete Cosey and Reggie Lucas, while Michael Henderson plays pounding, booming bass lines and Al Foster works the drums like a manic goblin.

On the opening track, listed on the cover as “Prelude”, but really starting with the riff from “Tatu” (which is, in a less rhythm-oriented version, also on Dark Magus), Miles, Fortune and Cosey perform an unprecedented musical exorcism as they sweep a rock/blues rhythm base with some of the wildest jazz improvisation on record. “Mayisha”, largely carried by Fortune’s flute, lets the listener cool down somewhat, but still manages to weave unbelievable solos into its relaxed texture. The second record, titled “Interlude”/”Theme from Jack Johnson”, but really containing elements from “Right Off”, “Ife” and “Wili” picks up speed again, and contains one of Miles’ best solos ever, followed by Cosey, Lucas and Fortune, who seem to play until exhaustion.

Agharta is a record of no compromises, a live set in which every musician gives (and, ultimately, spends) all the energy he has. Of the numerous high points in Miles’ career, this one is the one that shines darkest, and loudest. —Horst

Dave Brubeck “All The Things We Are” (1975)

We give you Dave Brubeck’s album “All The Things We Are”. Featuring Lee Konitz. And Anthony Braxton. Honestly, I didn’t make this one up. On paper, Braxton and Brubeck sound like the unlikeliest combination. Dave Brubeck, kingpin of college jazz in the 50’s and “Take Five” hitmaker; Anthony Braxton, mad scientist of the jazz avant-garde whose compositions look like a crash course in organic chemistry on the written page, and who most record companies (see his problematic relationship with Arista) don’t know how to handle. At least, that’s what the ayatollahs of jazz cliché would like to reduce them to. But things are never that simple. Both artists would appear to fly in the face of the “Jazz, delicious hot, disgusting cold” brigade (that expression courtesy of the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, who I believe lifted it from a music critic whose name I can’t, and don’t wish to, remember), because they know that even tricky time signatures and unfettered abstraction can lead to beguiling results and warm the adventurous heart.

Anthony Braxton had frequently declared himself a staunch admirer of Brubeck and of an unsung giant of modern music called Jimmy Giuffre. This may bring fits of apoplexy to Stanley Crouch, Wynton Marsalis and their followers, but it only seemed logical that the two finally connect. And you know what? It works. Of course, the presence of Roy Haynes on drums hardly makes matter worse. Brubeck duetting with Lee Konitz might seem like a less surprising combination, but is nonetheless just as effective. —Patrick

Duke Ellington “Far East Suite” (1966)

As the title suggests, the exotic melodies on this record will make one rethink their preconceptions of Duke Ellington and big band jazz. The King continued to explore and stay relevant into the sixties recording with exploring luminaries such as Coltrane and Mingus. As an already established jazz legend, Far East Suite is an example of how Ellington was not only a master composer and interpreter but was fearless and exploratory. The music on Far East Suite is at the same time accessible yet sinister and noir-esque. It was also years ahead of its time rhythmically — you can almost hear hip-hop beats on “Blue Pepper (Far East of the Blues).” —David

Oliver Nelson “The Blues and the Abstract Truth” (1961)

This is one of those jazz recordings that managed to capture lightning — that is to say, recording magic — in a bottle. Its pacing is perfect, its arrangements sublime, and the first-rate players, all of whom would be worth listening to on their worst day, offer inspired work.

Nelson, a fine tenor player in his own right, is surrounded by extraordinary talent: Eric Dolphy, Bill Evans, Freddie Hubbard, Roy Haynes. But this is Nelson’s album: not only does he play beautifully himself, he contributed the compositions and the arrangements, all of which have a note-perfect quality that could only be achieved by an artist in absolute command of his material.

Each tune is a joy in its own right, but the highlight for me (just ahead of the joyful “Hoedown”) is “Stolen Moments,” which has rightfully become a jazz standard. It’s a tune that never fails to remind me of the difference between a true jazz composition and a blowing session. In the latter, solos are taken for their own sake. In “Stolen Moments,” the solos are flawless, but each player extends on the previous statement. For example, the transition chord that Bill Evans plays between Oliver Nelson’s solo and his own is a perfect reply that shows how carefully he was listening to Oliver’s playing. The communication deepens the pleasure of listening to the performance.

Like Miles’ “Kind of Blue” and a handful of other jazz albums, “Blues and the Abstract Truth” could be put into a vault for listeners a thousand years hence to find. I’m sure they’d be just as impressed as the rest of us have been. —Tyler