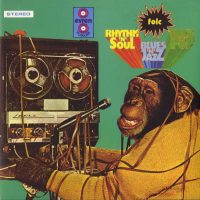

Spoken of in hushed tones by people who’ve eaten their weight in hallucinogens, Cottonwoodhill lives up to the hype. However, not everyone will dig the monomaniacal groove that dominates 26 of the album’s 34 minutes. It’s a helluva groove, granted, but some people have trouble with that sort of obsessive repetition. So, be forewarned.

Brainticket always get classified as “krautrock,” but they were based in Switzerland and their leader, keyboardist/flautist Joel Vandroogenbroeck, is Belgian; the other players on this LP hail from Italy and Germany. Whatever the case, these musicians created one of the most notorious head-wreckers in the rock pantheon. The warning on the inner gatefold—“Only listen once a day to this record. Your brain might be destroyed!”—is only slightly hyperbolic.

The album’s first song, “Black Sand,” starts in mid-gallop, born ready to sprint to the vortex of your cortex and stimulate the hell out of it. One of the great lead-off tracks in rock history, it’s a glinting slash of acid rock, marked by Ron Bryer’s burning liquid guitar leads, Vandroogenbroeck’s brash organ avalanches, and the most wicked, hollowed-out vocals (run through a Leslie speaker?). For most bands, “Black Sand” would be an album peak, but not here. Oh, no. Just you wait. “Places Of Light” is the mellow jam before the storm, with a mellifluous flute motif, poet Dawn Muir’s stoned intonations, and snarling organ riffs that would give Brian Auger Hammond envy.

So, about that peak… The two-part “Brainticket” begins with traffic/vehicle/horn sounds, out of which coalesces an über-repetitive master riff: a grinding, staccato behemoth of psychedelic propulsion that’s geared to zoom in and out for eternity. It’s the eventful foundation over which Muir rambles lysergically—hissing, gasping, groaning, and moaning the play-by-play of her harrowing LSD misadventure while what could be explosions in an analog-synth and Theremin factory transpire in the background. The whole track’s an existential freakout of frighteningly surrealistic intensity.

The first time I heard this album, I myself was on ac*d, and let me tell you, “Brainticket” loosened my already-tenuous grasp of reality, transporting me directly into the brains of the mad European musicians concocting this disorienting psych-concrète maelstrom. (It’s no mystery why Nurse With Wound sampled the main theme for their “Brained By Falling Masonry.”) “Brainticket” inevitably ends in cataclysmic cacophony, one woman’s awry trip alchemized into one of the most delirious psychedelic experiences on wax. You can’t not feel wrung out after listening to it. They don’t make ’em like this anymore… because most folks just can’t handle that level of madness… plus, it’s hard to market.

(The Lilith label reissued Cottonwoodhill in 2010, so you don’t need to spend three figures to hear this masterpiece on vinyl.) -Buckley Mayfield