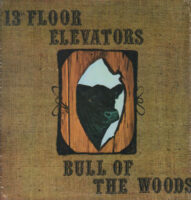

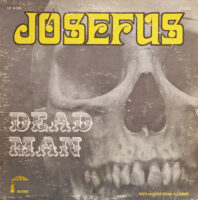

A human skull on a record cover usually leaves me cold, as I associate it with the sort of metal subgenres I find unappealing or the kind of edgelord industrial music for which I have no patience. For that reason, I avoided Josefus’ Dead Man for years, pre-internet. Finally, enough praise from reputable sources eroded my bias and I copped Numero Group/JR’s 2014 reissue. Ever since, the Southern-fried, hard-rock good times have been rolling at the Mayfield domicile.

The obi strip of my reissue hypes this Texas quartet as “being far ‘too psychedelic’ and skull-crushing for Houston’s International Artist label to touch.” I dunno about that, record-company guy, but Kenny Rogers’ bro Lelan did sort of blow it by not signing these sensitive hombres. I mean, Josefus were no Bubble Puppy, but come on…

The album starts with “Crazy Man,” whose midtempo, wistful boogie recalls Led Zeppelin’s “Hey, Hey, What Can I Do” and is buoyed by Pete Bailey’s biker-rock soul belting. Bailey comes off as something of a Lone Star State Robert Plant (but way more vulnerable), lending his singing a higher degree of pathos than Bob’s. “Crazy Man” establishes Bailey’s habit of choking up at crucial moments, which intensifies the songs’ poignancy. On “I Need A Woman,” Josefus grind out some testosteronic, ominous blues rock in which Bailey leers in a manner that would make ZZ Top blush, if not Greetings From L.A.-era Tim Buckley. Lust never sleeps.

Dead Man‘s nadir is, perhaps surprisingly, “Gimmie Shelter” [sic]. This adequate cover only serves to spotlight how awesome the Stones’ original—and indeed, Merry Clayton’s rendition—is. Josefus simply fail to invest the song with the ominous gravitas it demands, treating it more as an opportunity to rock a party. Dudes, you went on a fool’s errand (and misspelled “Gimme”), but Mick and Keith’s accountants surely appreciated your effort. However, Josefus rebound spectacularly with the album’s greatest cut, “Country Boy.” Drummer Doug Tull’s fantastic breakbeat in the intro gives way to a killer riff that lilts with a frilly panache. Bailey wishes/laments, “I’d love to spend some time being a rich girl’s toy/Because it seems so sad to be a country boy/Ain’t nobody out here who’s on my side/I’m so ugly I gotta stay in and hide/Sweet rich darlin’ let me be your toy/Because it seems so sad to be a country boy.” Even though I’m one of the world’s most urban mofos, I can sympathize with Bailey—which is a testament to the freighted emotion of his delivery.

With its marauding riff, unpredictable, prog-ish dynamics, and Plant-like wails, “Proposition” scans as the heaviest track on the record. So it’s apt—and kind of funny—near the end when the band quotes the Beatles’ “She’s So Heavy.” Album-closer “Dead Man” begins with a methodical ramble, its rhythm akin to the Doors’ “Five To One” and Ibliss’ “High Life.” Ray Turner’s bass riff is a master class in strutting hypnosis. The track’s marathon length allows guitarist Dave Mitchell to flex many of his flashiest riffs and Turner to generate a relentless, low-end cascade à la the MC5’s “Black To Comm.” There’s enough exciting ebbing and flowing dynamics and showmanship here to reward the listener for the duration of its 17 minutes. When the music’s over, turn out the lights.

Original copies of Dead Man have gone for hundreds and sometimes thousands of dollars. The only one for sale on Discogs now lists at $2,750. Pure insanity… Thankfully, reasonably priced, legit reissues shouldn’t be too hard to find. Find out once and for all why it seems so sad to be a country boy. -Buckley Mayfield