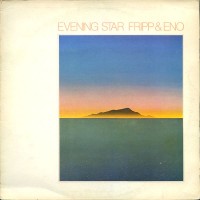

Evening Star‘s cover art—by Oblique Strategies co-creator Peter Schmidt—looks like fairly typical New Age LP fare, but the music therein is far from typical in that genre. This meeting of the prog-rock deities—King Crimson leader/guitarist Robert Fripp and former Roxy Music synth wizard Brian Eno—resulted in some of the most sublime ambient music this side of Discreet Music For Airports [sic]. Of course, the duo had cut the tape-delay masterpiece No Pussyfooting in 1973, its two sidelong tracks dilating listeners’ sense of time and ensnaring their minds in seemingly infinite loops. So fans were somewhat primed for another deep dose of head music. While not quite as lapel-grabbing as No Pussyfooting, the five tracks on Evening Star do possess a subtly alluring quality.

Opening track “Wind On Water” enters earshot on supremely gentle guitar ululations in the upper register, swathed in ambrosial drones that evaporate all cares and induce a preternatural calm. This makes “The Heavenly Music Corporation” off No Pussyfooting sound like heavy metal. “Evening Star” deepens the pervasive sense of tranquility. A gorgeous, crystalline three-note keyboard motif that should be your phone’s ringtone forever chimes in the foreground while Fripp launches foghorn-y wails in the background. An acoustic guitar jangles in the slim lacunae between those elements. The whole thing’s ecstatically lugubrious.

“Evensong” is a slight lullaby that pales in comparison to the two classics before it. However, the Eno solo composition “Wind On Wind” sounds like a benevolent god murmuring “there there” to you as she caresses your forehead. It’s a one-way ticket to Cloud 9, the key to absolute mental peace. Thus side one ends.

For side two, Fripp & Eno have something completely different in mind. Where side one floated in utmost placidity, the 28-minute “An Index Of Metals” tolls like an Emergency Alert System alarm. The tension is palpable from the start, and it only gets more ominous as it goes. The plot thickens with each passing minute, as Fripp’s guitar starts rolling in ever-larger waves, crashing on the shore of your ears with greater intensity and inhabiting more foreboding atmospheres. By the end of “An Index Of Metals,” you’re convinced it belongs in the pantheon of darkest music you’ve ever cowered to.

I’d wager it was Fripp who steered the ship into possibly the creepiest waters either musician had ever plunged. I keep thinking about the hilariously shocking transition that occurs on King Crimson’s debut LP, where the diabolical climax of “21st Century Schizoid Man” smacks abruptly against the utterly pacific “I Talk The Wind.” Fripp loves to subvert expectations. Your puffy-cloud fantasia’s been subsumed by a sinister undertow. Who is Eno to get in the way of that? -Buckley Mayfield