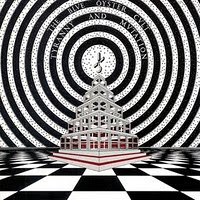

This 1973 outing is the album that raised Golden Earring to an international level of popularity, primarily on the strength of the hit single and enduring radio favorite “Radar Love.” However, there is much more to this album than just that hit.

It starts with a bang thanks to “Candy’s Going Bad,” a piece that starts off as a thunderous, pounding rocker but transforms midway into a bluesy instrumental mood piece. Other highlights include the hit single “Radar Love,” a relentless rock tune with a left-field instrumental break in which tribal drums duel with a big band-style horn section, and “Just Like Vince Taylor,” a guitar-slinging slice of boogie rock that pays tribute to the fallen rock idol of the title. The album also includes what may be the group’s finest prog effort in “Vanilla Queen”: this classic builds from pulsating, ominous verses dominated by synthesizer into a hard-rocking chorus and also throws in a stark acoustic guitar midsection before climaxing in a frantic band jam augmented by blaring horns and an ever-spiraling string section. Despite the album’s overall strength, not every song reaches these heights: “Are You Receiving Me?” recycles some hooks from the group’s past classic “She Flies on Strange Wings,” and the twangy country-pop of “Suzy Lunacy (Mental Rock)” is a little too poppy to gel with the rest of the album. However, even these tunes benefit from tight arrangements and a spirited, totally committed performance from the group.

The result is an album that retains its power today. In the end, Moontan is a necessity for Golden Earring fans, and a worthwhile listen for anyone interested in 1970s rock at its most adventurous. —Donald