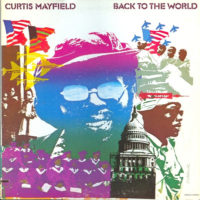

Imagine having to follow up Super Fly, one of the greatest soundtracks of all time and, to many listeners, a pinnacle of blaxploitation-film scores. No problem, though, for guitarist/vocalist Curtis Mayfield (no relation, by the way). The veteran R&B/soul/funk magus who established his rep with the Impressions showed he had plenty more inspiration from that gritty yet sumptuous palette on Back To The World, which peaked at #16 on the Billboard album chart and #1 on the R&B chart.

Wielding his supple falsetto and presenting himself as a sage street philosopher, Mayfield offered a concept album of sorts about a soldier returning from the Vietnam War and struggling to adjust to society and find a job. The buoyant, loping soul of “Back To The World” introduces you to this scenario, as it bursts with uplifting, swirling strings and punchy brass. Here and everywhere on Back To The World, Richard Tufo kills it with his ambitious arrangements, encompassing triumph and despair with panache. In a similar vein, “Right On For The Darkness” brings more dynamic, orchestral-funk drama. Sampled by everyone from Gang Starr to Insane Clown Posse, the song’s a lament for the human condition, particularly greed and temptation.

As for “Future Shock,” its stark, funky break has been sampled at least 23 times, and has been covered by Herbie Hancock on the same 1983 LP that bore “Rockit.” It’s certainly one of Mayfield’s most potent slices of message-heavy funk, laced with an ecological warning amid urgent horn stabs and weeping guitar interjections. Speaking of sample-worthy tracks, parts of “Can’t Say Nothin’” were lifted by Canadian hip-hop unit Dream Warriors for “U Could Get Arrested.” No wonder: its stealthy funk is as sleek and stylish as Dr. J breezing to the hoop during his ABA phase.

Back To The World climaxes on “If I Were Only A Child Again,” whose euphoric funk flaunts horn charts that inflate your heart to a planet-sized organ of joy. Mayfield’s protagonist expresses a desire to return to a state of innocence to avoid the grief caused by the way adults fuck up society. The music sweeps away any consternation the lyrics induce, exemplifying Curtis’ greatest feat—writing verses that depict hard times while composing music that elevates you far above their grim reality. -Buckley Mayfield