In order to contextualize some of the best Brazilian music of the 1970s, one must first understand tropicália (AKA tropicalismo). In order to do that, one must first look back to Brazil in the ‘60s, a nation at that time rife with contradictions. Despite intermittent political instability which culminated with a military coup in 1964, postwar Brazil simultaneously experienced unprecedented economic growth. A large portion of its population lived far below the poverty line, but its middle class grew exponentially, with many of its members now enjoying a standard of living that previous generations could only dream of. Not surprisingly, these changes began to manifest themselves in the music of Brazil. Bossa nova, in particular, enjoyed not only massive popularity in its homeland but in many countries in the northern hemisphere as well, making it Brazil’s most successful musical export since Carmen Miranda. At the same time, other new styles emerged on a seemingly daily basis. Aided by a growing radio and television industry and the proliferation of the LP format, a new Brazilian musical identity began to emerge, adopting the moniker of MPB (Música Popular Brasileira). Ironically, it was also around this time that a host of distinctly non-Brazilian styles, most notably American R&B and British Invasion, began enjoying popularity there as well. From there things would only get more complicated.

By 1966, a small but growing movement was afoot in the northeastern city of Salvador. Deconstructionist and remarkably post-modern in its approach, it sought to shatter all preconceived notions about Brazilian art and culture and reassemble these pieces into something entirely new. These “tropicalistas”, as they called themselves, at first largely consisted of artists, poets, and filmmakers. But when two up and coming musicians, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, entered the fold, Tropicália’s true legacy would become realized. Soon joined by a handful of other massive musical talents, among them Gal Costa, Tom Zé, and a trio of teenage Beatles fanatics calling themselves Os Mutantes, this unlikely collective would spearhead the Tropicália movement. Incorporating disparate musical styles ranging from traditional samba to psychedelic Hendrix-style guitar freakouts into their songs, nothing was sacred to the tropicalistas. This anarchic sonic collage can be heard in all its glory on the 1968 sampler LP, Tropicália: ou Panis et Circencis, which fired the opening salvo of a musical revolution that would prove to be very short-lived.

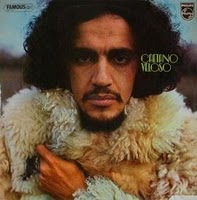

Tropicália’s tenuous existence was no surprise; in many ways, its founders were fighting a losing battle from the start. The left-wing intelligentsia thought them traitors for “corrupting” traditional Brazilian music with imperialist influences. The then in power military regime, of whom the Tropicalistas’ music openly and harshly criticized, hated them even more—so much so that they jailed and eventually deported Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil in 1969. With its two leading lights (temporarily) extinguished, Tropicália was basically over. But as far as what lay ahead for MPB, the real revolution had only begun.

For newcomers to Brazilian music, especially those steeped in a rock background, Tropicália often garners the most attention. This is not surprising, as it’s received a lot of press over the past decade and it has had some high-profile fans, Kurt Cobain and Beck among them. Much of what came after it in the following years might have lacked the aggression and visceral urgency that characterized Tropicália’s greatest moments, but the music of the post-Tropicália period was just as compelling, and perhaps even more diverse. Indeed, for many connoisseurs of Brazilian music, the early 1970’s represents an apex of innovation and excellence, a true Brazilian musical renaissance. Unfortunately, some of the best examples from this period can be tough to find outside of Brazil, but those willing to search will find the effort to be well worth it. Here are some titles to start with.

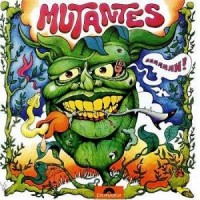

Os Mutantes Jardim Electrico (1970) Like their other later albums, this 1970 effort does not get as much attention as the “Tropicália trifecta” of their first three releases. This is not entirely fair. True, much of the endearing wackiness and Dadaist mayhem inherent in their earlier work are gone. But it’s all replaced with new-found confidence, more disciplined song structures, and tighter playing. Recorded mostly in Paris, Jardim Electrico shows the “Brazilian Beatles” vying for an international audience. One song, “El Justiciero”, is in Spanish. Two others, “Baby” and “Technicolor” are in English; the former makes a fine addition to the two versions recorded in Portuguese during Tropicália’s heyday while the latter, an entirely new creation, sums up the band’s raison d’être more effectively than anything they recorded before or after.

Os Mutantes Jardim Electrico (1970) Like their other later albums, this 1970 effort does not get as much attention as the “Tropicália trifecta” of their first three releases. This is not entirely fair. True, much of the endearing wackiness and Dadaist mayhem inherent in their earlier work are gone. But it’s all replaced with new-found confidence, more disciplined song structures, and tighter playing. Recorded mostly in Paris, Jardim Electrico shows the “Brazilian Beatles” vying for an international audience. One song, “El Justiciero”, is in Spanish. Two others, “Baby” and “Technicolor” are in English; the former makes a fine addition to the two versions recorded in Portuguese during Tropicália’s heyday while the latter, an entirely new creation, sums up the band’s raison d’être more effectively than anything they recorded before or after.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely.

Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our review) during his and Gilberto Gil’s exile in London. While Gil also recorded some great work during this period, he wouldn’t fully regain his stride until being allowed re-entrance into Brazil in 1972. Expresso 2222 shows an invigorated yet wiser-for-wear Gil serving up his best work since his 1968 Tropicália masterpiece, Gilberto Gil. His music is as playful as ever, as evidenced by the celebratory “Back in Bahia”, but also more mature and introspective. From here, Gil’s work became less consistent, seldom reaching these artistic heights.

Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our review) during his and Gilberto Gil’s exile in London. While Gil also recorded some great work during this period, he wouldn’t fully regain his stride until being allowed re-entrance into Brazil in 1972. Expresso 2222 shows an invigorated yet wiser-for-wear Gil serving up his best work since his 1968 Tropicália masterpiece, Gilberto Gil. His music is as playful as ever, as evidenced by the celebratory “Back in Bahia”, but also more mature and introspective. From here, Gil’s work became less consistent, seldom reaching these artistic heights.

Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS.

Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS.

Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Further listening: Towards the end of his tenure in the Talking Heads, David Byrne became obsessed with the modern sounds of Brazil (these influences can be heard all over the Head’s final album, Naked, and his 1988 solo effort, Rei Mono). He founded a record label, Luaka Bop, which issued a various Brazilian artists sampler, Beleza Tropical, as its first release in 1989. Although it covered some more contemporary material, its emphasis was on material released in the ‘70s. Byrne stated that he hoped the record would do for Brazilian music what The Harder They Come soundtrack did for Jamaican music. While this was probably an unrealistic goal, Beleza Tropical did have an impact, and it’s doubtful that few outside of Brazil would know who Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil are had it not been released. Though missing some key artists and tracks, it provides a decent introduction for newbies. But it was the London-based Soul Jazz Records who really nailed it with their 2007 release, Brazil 70. Stuffed with tracks from all corners of the Brazilian renaissance of the 70s, it is probably the best compilation of its kind to be released so far. Here’s hoping for a second volume! —Richard P

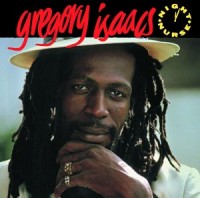

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae.

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae. Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music.

Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music. Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today.

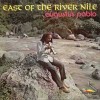

Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today. Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision.

Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision. Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely.

Lô Borges Lô Borges (1972) Guitarist Lô Borges was a charter member of Clube de Esquina , a musical collective somewhat overshadowed by the troipicalistas but every bit as inventive as their counterparts. His solo debut, however, deserves to stand on its own. Here Borges’ exquisite songwriting is enhanced by an intoxicating mix of jazz, funk, psychedelia, and traditional Brazilian forms. This record is one of those “unknown” masterpieces that is spoken about in hushed tones among hipsters and music nerds and which, over time, gains “classic” status and a huge following. Does it live up to its hype? Absolutely. Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our

Gilberto Gi Expresso 2222 (1972) Caetano Veloso recorded one of his definitive masterpieces (read our  Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS.

Secos e Mulhados Secos e Mulhados (1973) Secos e Mulhaldos examplified MPB’s increasing penchant for straight-ahead rock. But while their glammy debut exhibits some ‘70s arena rock traits, in the end it’s one of those records that’s impossible to categorize. Echoes of Marc Bolan and David Bowie can certainly be heard, but this is often underscored by a distinctly Brazilian folk vibe. What truly defines its uniqueness, however, are Ney Matagrosso’s androgynous vocals. (Newcomers to this record are often stunned when they learn that the lead singer of this band is actually a male.) Hugely popular in Brazil during their brief mid-70s run, the band’s Latin American kabuki stage getup was supposedly a direct inspiration for the outrageous outfits appropriated by KISS. Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Tom Zé Estudando o Samba (1975) Of all the tropicalistas, Tom Zé retained the movement’s experimentalist M.O. more than any of his peers, sometimes not in his best interests commercially. But this 1975 album strikes a perfect balance between joyous samba and dissonant musique concrete. “Toc” overlays a cacophony of found sounds consisting of typewriters, radio static, and crying babies on top of one note continuously plucked on a guitar. It’s a testament to Zé’s talent that such aural collages can sit comfortably alongside a song like “Tô”, which wouldn’t be out of place on a Stan Getz record. Somehow, Zé keeps one foot in the avant-garde and the other in a carnival procession, and this is what makes his music so fantastic.

Orlando Julius & His Modern Aces Super Afro Soul (2000) While Fela would become Nigeria’s most recognizable musical icon, Orlando Julius was the country’s first true pop superstar. A major purveyor of hIghlife in the mid-60s, Julius diverted from the rest of the pack by incorporating Stax and Motown influences into his sound, creating an infectious hybrid of highlife and soul. Though revered by many musicians outside of his homeland, Julius never found the massive international audience that he deserved. Fortunately, British label Strut Records sought to remedy this by reissuing this album, which highlights this fertile period of his career.

Orlando Julius & His Modern Aces Super Afro Soul (2000) While Fela would become Nigeria’s most recognizable musical icon, Orlando Julius was the country’s first true pop superstar. A major purveyor of hIghlife in the mid-60s, Julius diverted from the rest of the pack by incorporating Stax and Motown influences into his sound, creating an infectious hybrid of highlife and soul. Though revered by many musicians outside of his homeland, Julius never found the massive international audience that he deserved. Fortunately, British label Strut Records sought to remedy this by reissuing this album, which highlights this fertile period of his career. Fela Ransome Kuti & Ginger Baker Live! (1971) Cream drummer Ginger Baker was rock royalty’s earliest adopter of Nigerian music. Building a state of the art recording studio in Lagos in the early 70s, he is widely credited for introducing the music of Nigeria to western audiences. Baker and Fela met in London in the late 60s, resulting in a lifelong personal and musical friendship that would benefit both of them. This recording, made in a London club in 1970, showcases the two icons joining forces to deliver a killer set. Baker’s drumming not surprisingly sometimes gives it a more rock-like feel, making this a unique entry in Fela’s catalog.

Fela Ransome Kuti & Ginger Baker Live! (1971) Cream drummer Ginger Baker was rock royalty’s earliest adopter of Nigerian music. Building a state of the art recording studio in Lagos in the early 70s, he is widely credited for introducing the music of Nigeria to western audiences. Baker and Fela met in London in the late 60s, resulting in a lifelong personal and musical friendship that would benefit both of them. This recording, made in a London club in 1970, showcases the two icons joining forces to deliver a killer set. Baker’s drumming not surprisingly sometimes gives it a more rock-like feel, making this a unique entry in Fela’s catalog. Fela Anikulapo Kuti & Africa 70 Gentleman (1973) When confronted with the bewildering size of Fela’s catalog, many people often ask the same question: “Where should I start?”. Really, pretty much any of his studio albums released between 1971 and 1978 will make anyone a fan for life. But this album is where the template for Fela and Africa 70’s incendiary brand of afrobeat was truly established. Its title track, with Fela’s blistering sax (an instrument that he allegedly learned and mastered in just a few days following the departure of Africa 70 tenor saxophonist, Igo Chico), is worth the price of admission alone.

Fela Anikulapo Kuti & Africa 70 Gentleman (1973) When confronted with the bewildering size of Fela’s catalog, many people often ask the same question: “Where should I start?”. Really, pretty much any of his studio albums released between 1971 and 1978 will make anyone a fan for life. But this album is where the template for Fela and Africa 70’s incendiary brand of afrobeat was truly established. Its title track, with Fela’s blistering sax (an instrument that he allegedly learned and mastered in just a few days following the departure of Africa 70 tenor saxophonist, Igo Chico), is worth the price of admission alone. Peter King Shango (1974) A classically trained composer and saxophonist, Peter King is yet another criminally overlooked master of afrobeat. In the 70s, he recorded a handful of records containing a winning mix of jazz, funk, soul, blues, salsa, and, of course, rhythms from his own homeland of Nigeria. This can be heard in all its hip-shaking glory on this record, which unfortunately to date remains his only one to be reissued.

Peter King Shango (1974) A classically trained composer and saxophonist, Peter King is yet another criminally overlooked master of afrobeat. In the 70s, he recorded a handful of records containing a winning mix of jazz, funk, soul, blues, salsa, and, of course, rhythms from his own homeland of Nigeria. This can be heard in all its hip-shaking glory on this record, which unfortunately to date remains his only one to be reissued. The Daktaris Soul Explosion (1998) You would never know it, but this album was actually recorded in the late-90s by a bunch of guys from Brooklyn, many who would go on to form Antibalas Afrobeat Orchestra soon after its release. So convincing was its vintage sound and packaging, however, that many collectors were sure that they had stumbled upon a long lost afrobeat classic. (One of the evil geniuses behind this ruse was Gabriel Roth, eventual founder and boss of Daptone Records.) Despite the gimmickry, it’s the music that has to deliver in the end, and it does so in spades. Dedicated to Fela, the album kick-started the afrobeat revival. thereby keeping his torch ablaze while proudly carrying it into the 21st century.

The Daktaris Soul Explosion (1998) You would never know it, but this album was actually recorded in the late-90s by a bunch of guys from Brooklyn, many who would go on to form Antibalas Afrobeat Orchestra soon after its release. So convincing was its vintage sound and packaging, however, that many collectors were sure that they had stumbled upon a long lost afrobeat classic. (One of the evil geniuses behind this ruse was Gabriel Roth, eventual founder and boss of Daptone Records.) Despite the gimmickry, it’s the music that has to deliver in the end, and it does so in spades. Dedicated to Fela, the album kick-started the afrobeat revival. thereby keeping his torch ablaze while proudly carrying it into the 21st century.

1. Prince Buster: Fabulous Greatest Hits (1980) – Though acquiring a popularity in the UK that at its peak rivaled the Beatles’s, Prince Buster never really established a large following in the US. Tracking down his one uneven RCA release from 1967 is a worthwhile endeavor, but this 1980 British comp is where all newcomers should start. All songs here were recorded in the mid to late ’60s, and many of them would serve as the blueprint for the 2 Tone movement that swept the UK a decade or so later.

1. Prince Buster: Fabulous Greatest Hits (1980) – Though acquiring a popularity in the UK that at its peak rivaled the Beatles’s, Prince Buster never really established a large following in the US. Tracking down his one uneven RCA release from 1967 is a worthwhile endeavor, but this 1980 British comp is where all newcomers should start. All songs here were recorded in the mid to late ’60s, and many of them would serve as the blueprint for the 2 Tone movement that swept the UK a decade or so later. 2. Desmond Dekker and the Aces Israelites (1969) “The Jamaican Smokey Robinson’s” single “Israelites” represents the only time when rocksteady cracked the US top 100. When it did, MCA rushed to cobble together this collection of songs, some of which by then were almost two years old. It’s still a fantastic showcase for some of Dekker’s best work. He’s at the top of his game here, and so is his backing band.

2. Desmond Dekker and the Aces Israelites (1969) “The Jamaican Smokey Robinson’s” single “Israelites” represents the only time when rocksteady cracked the US top 100. When it did, MCA rushed to cobble together this collection of songs, some of which by then were almost two years old. It’s still a fantastic showcase for some of Dekker’s best work. He’s at the top of his game here, and so is his backing band. 3. The Ethiopians Engine ’54: Let’s Ska and Rocksteady (1968) Rocksteady was the ideal vehicle for the vocal group, and as Jamaican vocal groups went, they didn’t get much better than the Ethiopians. Don’t let the “ska” in the title fool you; most of this is quintessential rocksteady, some of the best ever recorded.

3. The Ethiopians Engine ’54: Let’s Ska and Rocksteady (1968) Rocksteady was the ideal vehicle for the vocal group, and as Jamaican vocal groups went, they didn’t get much better than the Ethiopians. Don’t let the “ska” in the title fool you; most of this is quintessential rocksteady, some of the best ever recorded. 4. The Upsetters The Upsetter (1969) It’s difficult to figure out to whom this album should really be credited. One should know, however, that a young Lee “Scratch” Perry produced it, and whenever this eccentric mastermind is involved, things become, well… complicated. Featuring the work of a cadre of different musicians and vocalists, it’s a surprisingly cohesive late rocksteady record, one where the organ figures more prominently than the work of others at the time. It also hints at the dub revolution, of which Perry would be a prime architect a few years later.

4. The Upsetters The Upsetter (1969) It’s difficult to figure out to whom this album should really be credited. One should know, however, that a young Lee “Scratch” Perry produced it, and whenever this eccentric mastermind is involved, things become, well… complicated. Featuring the work of a cadre of different musicians and vocalists, it’s a surprisingly cohesive late rocksteady record, one where the organ figures more prominently than the work of others at the time. It also hints at the dub revolution, of which Perry would be a prime architect a few years later. 5. Various Artists Tighten Up: Volume 1 (1969) Music from Jamaica continued to capture the hearts and minds of young UK listeners in the late ’60s, but the record industry was slow to profit from its popularity. This Trojan Records “cash-in” comp. spawned a series that would become an institution and number well into the double digits before ending its run. Its first volume defined the musical tastes of the Skinhead movement (before it was co-opted by nationalist and racist thugs). Heavy on soul covers, a few of its tracks denote a distinct progression towards reggae, but most represent some last great moments from Rocksteady’s waning days.

5. Various Artists Tighten Up: Volume 1 (1969) Music from Jamaica continued to capture the hearts and minds of young UK listeners in the late ’60s, but the record industry was slow to profit from its popularity. This Trojan Records “cash-in” comp. spawned a series that would become an institution and number well into the double digits before ending its run. Its first volume defined the musical tastes of the Skinhead movement (before it was co-opted by nationalist and racist thugs). Heavy on soul covers, a few of its tracks denote a distinct progression towards reggae, but most represent some last great moments from Rocksteady’s waning days.