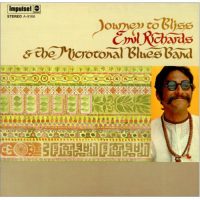

Sometimes you can judge a record by its cover. Check out Journey To Bliss by Emil Richards & The Microtonal Blues Band. Dig the Sanskrit font on the front cover, as well as the hypnotic patterns in the painting, and Richards wearing a beatific grin and a top native to India. The back cover features a Van Gogh-esque painting of a swami. And though it’s a Bob Thiele production bearing the Impulse! imprint, Journey To Bliss ain’t your father’s typical jazz record… unless your pop is Timothy Leary. This is a venerable jazz label trying to cash in with a psychsploitation elpee. It didn’t quite win over the kids, but heard over 50 years later, Journey To Bliss still has the power to charm.

Impulse! helpfully provides a list of all the instruments used by the Microtonal Blues Band (who include Wrecking Crew guitarist Tommy Tedesco; Richards was a well-connected LA session muso). It runs to 57 items. Some of the more obscure ones include flapamba, tumbeg, crotales, dharma bells, temple blocks, surrogate Kithara (a variation of a Harry Partch invention), and boobams. So there you go. Buckle up for a strange ride the likes of which you likely have never experienced, unless you’re familiar with the catalog of the aforementioned Partch.

“Maharimba” instantly launches into a jaunty jazz-exotica gait in 7/4, piquant percussion timbres flying everywhere; big ups to those tuned wastebaskets. This song could segue nicely out of Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five,” even though it’s in a different time signature. “Bliss” proves that 11/4 is a very good time. It tumbles headlong into the titular state with an array of sublimely slapstick percussion timbres (22 tone xylophone and who knows what else). The peppy and peripatetic “Mantra” (in 5/4) unsurprisingly comes across like Brubeck meeting Partch at the cantina. “Enjoy, Enjoy” is a strangely undulating tune just rippling with extranjero percussion. Periodically you’ll hear Hagan Beggs narrating some mystical mumbo jumbo that was in vogue during the late ’60s over the music. This may be a deal-breaker for some, but I like the dude’s sense of wonder and sonorous delivery.

Side two is dominated by the 18-minute “Journey To Bliss,” and what an oneiric odyssey through intriguing paths of Eastern music it is. “There is a river running through me and sometimes I let it pull me in/it cradles me in its ever-so-gently rocking current and carries me along to bliss,” Beggs intones in a hypnotist’s cadence, not too different from Timothy Leary’s on Tune In, Turn On, Drop Out. It works well over the faux-gamelan ritual procession.

The final two parts of the six-part suite build to a tumultuous climax, with scorching sitar riffs and Rashied Ali-esque drum splatter—and loads of dissonant bell tones. If this is bliss, it’s a particularly hectic strain of it. Beggs proclaims, “My heart is the sun/My body is the universe/My soul iiiiiisssssssss” [cacophony engulfs everything] “Jai guru dev.” (Translation: Victory to the Greatness in you.) And scene.

Goodness gracious. It’s all too much… thankfully. -Buckley Mayfield