She was a superstar in the 1930’s and 40’s. She introduced Bing Crosby to the music of Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith. She worked with the most famous big bands of the era. Tony Bennett said

She was a superstar in the 1930’s and 40’s. She introduced Bing Crosby to the music of Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith. She worked with the most famous big bands of the era. Tony Bennett said

“From 16 to 20 years old the only thing I listened to was Mildred Bailey. I just said I want to sing like her” She provided the template for the “girl singers” from Ella Fitzgerald to Anita O’Day. She introduced Billie Holiday to the famous producer John Hammond. She started from the speakeasies of Spokane and Seattle and made her way to Los Angeles and then to The Savoy Ballroom and Stork Club in New York City. Yet Mildred Bailey and her contributions to jazz and pop music have all but been disregarded. She is the most famous jazz singer of the 1930s and ‘40s that you’ve never heard of.

Over the years there’s been attempts to replace her to the stature she once had, but she still remains a cult figure who is absolutely loved by her fans. Every one of her recordings have been available for years-most of them have been in continual release since 1951 when she died. Her entire Columbia Records catalogue has been lavishly presented as boxed sets in both LP and CD formats for decades. So it must be asked-in the words of jazz critic Michael Steinman; “Who Erased Mildred Bailey?” It certainly wasn’t singers like Tony Bennett,mentioned above. It wasn’t Bing Crosby or Frank Sinatra who helped her out at the end of her life. It wasn’t a change in taste; The Big Band sound and jazz/pop singers were in their heyday when she quit the music industry. It wasn’t for a lack of exposure on the new media of television…she even had her own television program at one time.

The fact is that there doesn’t seem to be a simple answer to why Mildred Bailey has been erased from our collective musical consciousness, and the answer remains elusive to this day.

Mildred Bailey was born Mildred Rinker on February 27, 1903 in Tekoa Washington, a small farming community about an hour southeast of Spokane Washington. Mildred’s mother, Josephine had been deeded land there and created a farm on the land she owned. Josephine was one quarter Native American. Her ancestors were what became known as the Coeur d’Alene tribe. Owners of valuable property by tribal members was unusual at the time: so while the Coeur d’Alene people were generally living in poverty, Mildred’s family were more economically secure. Until the age of 13 her family lived in De Smet Idaho. Though miles apart,both communities (De Smet where she lived and Takoa where she was born) butted up on the Washington/Idaho border (each one on different sides). It’s thought her father Charles Rinker was of Irish/Swiss descent but because of her mother’s tribal affiliation Mildred’s early upbringing was spent on the Idaho side of the border the family lived on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation which at the time was (and still is) within the confines of the state of Idaho. According to her tribe’s custom, inclusion into the tribe is based on either maternal or paternal lines. Mildred’s lineage as a Native American came directly through her mother who was a full member of the Coeur d’Alene tribe.

The tribe’s modern name, Coeur d’Alene was arbitrarily bestowed upon them by the first French traders that operated in the area. The literal translation of Coeur d’Alene to English is “heart of an awl” or more colloquially, “pointed hearts”. The name was given to them because they were tough negotiators with European traders. It’s unclear if the designation “pointed hearts” was due to a respect for the natives or as a derisive term based on their generally seeking the upper hand in matters of commerce. As traders came to be more common in the area, Catholic missionaries moved in and converted most of the people of the nation are Roman Catholic and many place names on the area are French. Most tribal members today are Catholic, but in recent decades younger members are returning to their traditional spiritual roots.

The Coeur d’Alene name has stuck as the preferred name the US government and Idaho state uses to designate the tribe, but they themselves have always called themselves “Schitsu’umsh” or “Skitswish” meaning “The Discovered People” or “Those Who Are Found Here”. Traditionally the Coeur d’Alene homeland included most of Idaho’s panhandle, a portion of Eastern Washington and Western Montana. The historical north/south borders spanned between the lower end of Lake Pend Oreille at the northern extreme and The Palouse Hills to the south, and the Clearwater River to Spokane Falls. The homeland originally consisted of more than 3.5 million acres of forests, mountains, lakes, rolling plains, marshes and rivers. The entire Coeur d’Alene (or Schitsu’umsh) territory has now been reduced to a 345,000 acre reservation, all of it within the state of Idaho, abutting the Washington State border.

At the time of Mildred Rinker’s birth in 1907, the Schitsu’umsh people lived in poverty, surrounded by mining operations in and around the reservation that stripped the land of minerals, leaving much of the land and water was left damaged and polluted. The environmental conditions were so bad and so prevalent that in recent years the tribal council has brought several (successful) civil actions against the US government and private mining corporations-ASARCO being the worst offender. In 2014 then-Idaho House Representative Paulette Jordan claimed the industries “left several thousand acres of land and tributaries connected to the Coeur d’Alene Basin, contaminated with heavy metals”.

According to the tribe’s website;.

“These mining operations have contributed an estimated 100 million tons of mine waste to the river system.Over a 100 year period the mining industry in Idaho’s Silver Valley dumped 72 million tons of mine waste into the Coeur d’ Alene watershed. The State of Idaho, meanwhile, looked the other way. As mining and smelting operations grew, they produced billions of dollars in silver, lead and zinc. In the process, natural life in the Coeur d’ Alene River was wiped out. In 1929, as the river flowed milky-white with mine waste, a Coeur d’Alene newspaper reporter described a river trip to the Silver Valley a “Up the River of Muck and into the Valley of Death.”Today, the Silver Valley is the nation’s second largest Superfund site. The natural resource damages, however, extend upstream and far downstream from the 21-square mile “box” that is now under Superfund”.

All of this may seem extraneous to the story of Mildred Bailey, but it helped shaped her reaction to adversity both in positive and negative ways. It also informed her view of discrimination and the downtrodden, So it was into this environment that Mildred, her three brothers were born.. Despite the surroundings the Rinker siblings were also fortunate to be exposed to music all their lives. Their mother, Josephine, played piano and taught all of them to play at an early age. Mrs.Rinker had studied music at the Catholic Academy in Tekoa.. It’s said that she was proficient in both classical music as well as all the current popular genres sweeping the nation. Their father, Charles Rinker was a fiddler who took part in local squaredances and also took time to teach his children as much music as he could. The family spent many a night playing and singing, often with neighbors joining in.

By the time Mildred was 13 years old the Rinker family had moved to the city of Spokane Washington. In 1912, Charles Rinker had bought one of the first automobiles in the Takoa area and upon his work-related trips to Spokane he found he was more suited to city life. The Rinkers leased their farm and moved 60 miles to the city…already Washington State’s second largest metropolis.,. Mildred’s father opened an auto supply shop. It was after this move that Mildred and her brothers became more closely involved in music as a vocation. Mildred was enrolled at St. Joseph’s Academy, where she studied piano and her brothers continued to learn piano with their mother at their side.

In 1916 their mother Josephine died. Various reports indicate the cause of death being either tuberculosis or The Spanish Influenza. Soon after the death of Mrs Rinker, Charles Rinker remarried. According to Mildred Bailey biographer Gary Gibbin the second Mrs Rinker was;

“an abusive, grasping woman, who moved in with her daughter while insisting he send his kids to boarding school”. Charles Rinker resisted her threats, trying to keep the family together, but Mildred despised her”.

Even so the house was still filled with music. Al Rinker remembers his step-mother at the piano singing songs of longing and faraway places: Rinker recalled some of her favorites were “Siren of the Southern Seas,” “Just a Baby’s Prayer at Twilight,” and “Araby.” among others.

After putting up with her step mother for about a month Mildred packed her bags and headed for Seattle to live with an aunt We know that for a few months Mildred demonstrated and sold sheet music at Woolworth’s in downtown Seattle. She also began singing in some of the local speakeasies. Within a year she married a man named Ted Bailey. The marriage was brief, but upon the couple’s divorce Mildred chose to keep the surname Bailey. She believed it sounded more professional, and more American than her birth name, Rinker. It’s not coincidental that Mildred chose Bailey over Rinker; her given name sounded vaguely Teutonic and WWI had aroused suspicion and overt abuse toward anyone suspected of being of German heritage.

After her father’s divorce from her step-mother Mildred returned to Spokane and once again began to demonstrate and sell sheet music; this time at Spokane’s Baileys Music Store-the name of the store and Mildreds surname were coincidental. Her brother Al began hanging out at the shop and brought along one of his friends, a young singer named Bing Crosby. Soon the three of them became fast friends and hang out at the store on Riverside Avenue where Mildred briefly worked. The three no doubt spent time strategizing about their future careers.

This was the era of Prohibition and the speakeasy. Mildred would spend the next few years travelling up and down the west coast singing her way from Seattle and Los Angeles to Vancouver BC and as far afield as Alberta.

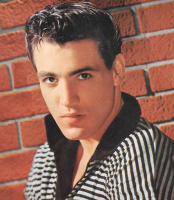

Mildred’s Spokane break came with a one night singing engagement at Spokane’s most popular speakeasy Charlie Dale’s. It’s said that Bing Crosby saw her at Charlie Dale’s that night and called her “the area’s outstanding singing star” Even though Mildred was obviously talented and fashionably lithe at barely five foot tall and weighing under a hundred pounds, Bing’s statement may be apocryphal, but he later remembered her as “specializing in sultry, throaty renditions with a high concentration of southern accent such as “Louisville Lou” and “Hard Hearted Hannah” That would be far closer to the truth, even if she eventually perfected her style in much the same manner. And she had not yet become the heavy-set, matronly figure she’d later become popularly associated with.

Soon Mildred was off to Los Angeles hoping to pursue her singing career in popular speakeasies. Biographer Giddens reports that

“Mildred and Benny moved to Los Angeles where they bought a house at 1307 Coronado Street, a few blocks off Sunset Boulevard. He was prospering with his bootlegging and she was earning a reputation singing sad songs in local dives”.

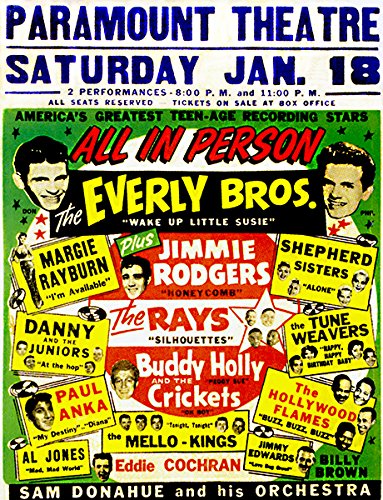

By 1925 Mildred was singing at Jane Jones’s Hollywood Hills speakeasy-a popular watering hole for the Hollywood elite. During her stint she had convinced brother Al and his buddy Bing to come to Los Angeles. Still, it was a shock when the two showed up unannounced. However as the older more experienced artist she allowed them to stay and showed them the ropes to survive in Los Angeles.

By this time Mildred had begun to put on weight-a condition that would follow her the rest of her life. She also cemented her life-long friendship with Bing Crosby, who would later come to her aid. During he and Al’s first months in Hollywood Bing called Mildred “mucho mujer”, a great talent. Within a few months Mildred, through her connections, had the famous bandleader Paul Whiteman have a look at Al, Bing and Harry Moss (The Rhythm Boys). After one audition Whiteman hired them as featured vocalists in his Orchestra.

Three years later, before Bing went solo, he and Rinker returned Mildred’s favor by getting Whiteman to have a look at Mildred onstage. At the time The Rhythm Boys were involved in the filming of Paul Whiteman’s film The King of Jazz . Al Rinker later retold the story that Bing Crosby could only film during the day. He was on work release after hitting a telephone pole while driving drunk!

The film and Whiteman’s orchestra were in a state of disarray at the time.. Whiteman had no time audition a new singer, and that same week he saw Mildred he had turned down Hoagy Carmichael. The three (Al, Bing and Mildred) concocted a plan. Mildred was friends with several members of Whiteman’s orchestra and invited them and the bandleader to a “going away party” where she would serve her own well-regarded homebrew, taking advantage of the well-known fact that Whiteman was a heavy beer-drinker.

At some time during the party Bing Crosby (on cue) asked Mildred to sing something. At first she pretended to be too embarrassed, but finally she asked brother Al (as planned) to accompany her on “(What Can I Say) After I Say I’m Sorry?”

She nailed it.

Whiteman was impressed, asked her to sing an encore, and by the end of the party had made arrangements for Mildred to appear on his Old Gold radio show. Although she was not an outright member of The Paul Whiteman Orchestra within the year Mildred Bailey became Whiteman’s highest-paid musician.

The story may or may not be true, but it’s an interesting one. There are other reports that Whiteman only became familiar with Mildred Bailey through a demo recording she’d made. We’ll never know if the party stunt was ever employed-but it makes for a good story, and it’s as likely as any other.

Mildred’s was making her ascent to becoming the most well-known singer of her era. Soon the critics were heralding her as the first “white” singer to be compared with black singers such as Ethel Waters. Bessie Smith and those taking advantage of the syncopation Louis Armstrong had brought to jazz. This claim, however, dismissed the fact that Mildred had a strong Native American heritage and she was proud of it. She made no attempts to hide her ancestry, and was one of the first American celebrities to actually stand up for racial equality. It would be years before her ancestry was truly recognized and admitted among her fans and champions. But even then there was some confusion. Some believed she was black. Others believed she was of mixed race-the former being true, but the races assumed being incorrect. As late as 1994 The US Postal Service issued a series of stamps commemorating the great Black blues and jazz musicians that had made notable contributions to American music. The series included Bessie Smith, Muddy Waters, Billie Holiday, Robert Johnson, Jimmy Rushing, Ma Rainey, Howlin’ Wolf…and Mildred Bailey, the only non-African American in the series. It’s hard to say if this was a case of mistaken racial identity or not, but one other problem with the Mildred Bailey stamp is that it is printed with the wrong year of her birth (1907 instead of the correct 1903).That, however is a common mistake.

It wasn’t the first time Mildred was assumed to be African American. Nothing of consequence was made of her ethnicity in the jazz world (except for later, after Prohibition ended). Because the milieu she worked in, it was populated by people of color. But to be Native American during the early to mid 20th Century could be even worse than being black and discrimination was widely practiced. In fact even in the early 21st Century discrimination and outright dislike of Native Americans is not unusual. But within the jazz world things were more relaxed since it wasn’t a strictly whites-only profession. In fact Mildred Bailey believed that the Native American music she grew up with had influenced her style. In an essay by Chad Hammill “American Indian jazz: Mildred Bailey and the origins of America’s most musical art form” the author cites Mildred Bailey as saying:

““I don’t know whether this (native) music compares with jazz or the classics, but I do know that it offers a young singer a remarkable background and training. It takes a squeaky soprano and straightens out the clinkers that made it squeak; it removes the boom from the contralto voice, this Indian singing does, because you have to sing a lot of notes to get by, and you’ve got to cover an awful range.”

In any event by the 1930s Bailey had created a sound of her own that acted as a transition from the old blues belters (like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey,) to the breezier, jazz interpretations of Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. It’s especially easy to hear Bailey’s influence over Billie Holiday, even though Bailey’s style is slightly stiffer, more clearly enunciated and her voice not as sultry and breathy as Billie’s. The years of.

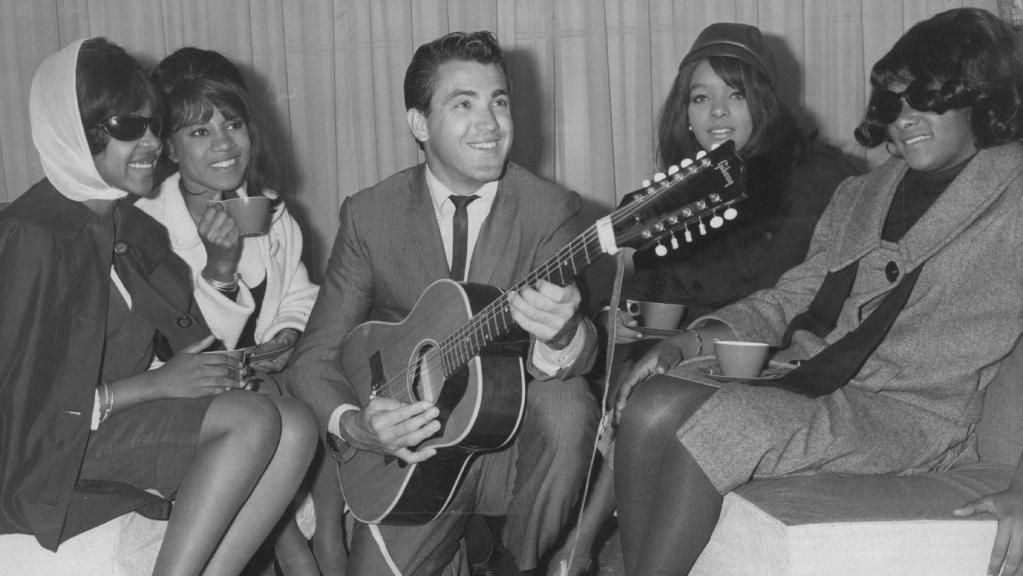

Mildred’s success set off the popular format of the “girl singer”. The name might not be politically correct today, but at the time of the “girl singers” it referred to the women who Big Bands featured to interpret well-known songs, try out new material for up-and-coming songwriters and provide a few torchlight songs in order to break up the big band’s mostly instrumental presentation. Most women singing with the big bands were and are referred to “girl singers”. Women as diverse as Mildred Bailey herself to Doris Day, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Lena Horne, Anita O’Day, Kay Starr and Helen O’Donnell. The list goes on and on. One of the attractions of the “girl singers” is that they usually sang for several big bands, some for a few years at a time, and others working with several bands simultaneously. This offered fans of both the singers and the big bands a heady mix of styles and sounds.

Mildred first recording was a 1929 uncredited vocalist for a session by the Eddie Lang Orchestra in 1929 (“What Kind o’ Man Is You?”), Her next was a Hoagy Carmichael song that was issued only in the UK). In 1932 she recorded what would be her signature song, “Rockin’ Chair” written by Hoagy Carmichael in 1929. The song became so popular that she would be known as The Rockin’ Chair Lady”. It was a name that would stick.

By 1933 Prohibition and the era of the speakeasy had ended and Mildred Bailey found herself more and more in demand. She toured the country, played legitimate nightclubs, dance halls and ballrooms. She made frequent radio appearances. She continued to work with the best big bands of the day, and created several herself to back her. Bailey’s backup bands were never less than first-rate. Besides Norvo’s ensemble, she’s accompanied on these vintage recordings by the Casa Loma Orchestra, the Benny Goodman Orchestra and a band led by the Dorsey brothers, Jimmy and Tommy. According to Owen McNally of the Hartford Courant;

“There’s a classic blues session with pianist Mary Lou Williams (a powerful, groundbreaking female figure in the sexist jazz world) and more than 20 tracks with the John Kirby Orchestra, an early chamber jazz group that was a forerunner of the classicism of the Modern Jazz Quartet. There are witty arrangements by Eddie Sauter and composer Alec Wilder’s progressive, third-stream charts for an octet. Wilder scored for oboe, English horn, bass clarinet and flute — instruments then not much associated with jazz”.

One blatantly missing facet of her career was appearances in feature films. She certainly had the popularity of other singers who were featured. It may have come down to her being less photogenic than her peers. She continued to gain weight, and there was no escaping she was obese. Her biographers believe she made a Vitaphone short, and possibly one for Universal but as of 2018 they haven’t been discovered.

She remained popular throughout the 30’s but even more fame came after she married her third husband, Red Norvo (Kenneth Norville) . Norvo had been a vibraphonist, marimba player and xylophonist who brought those instrument to the fore in many jazz recordings. He’d started his career playing in an all-marimba band on the vaudeville circuit, and early on in his career had become part of Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra in 1931. It was there that he and Bailey met. Soon afterward they married, Mildred having dumped her second husband, the bootlegger. Norvo would go on to be one of the most influential figures in jazz. After a brief stint with Whiteman, Norvo went on to form his own band. During his career he would come to work as a soloist, with his own band and a featured player on the recordings of Benny Goodman, Charlie Barnet, and Woody Herman, Billie Holiday, Dinah Shore and Frank Sinatra. Norvo was a non-conformist and attracted to the newer movements in jazz. During his later years-after the popularity of big bands came to a close- he would play with bebop luminaries such as Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker as well as establishing a name for himself

Shortly after marrying Mildred, Norvo’s band was on the verge of collapse. Mildred offered to step in and bring some of her popularity to Red’s band. The coupling saved Norvo’s band and both played off each other, creating some of their finest music. After success the couple became known as “Mr. and Mrs. Rhythm” Now Mildred had two nicknames “The Rockin’ Chair Lady” and “Mrs. Swing” It’s been said the thin “Mr. Swing” pounding out near-athletic backing on vibes and xylophones and the corpulent “Mrs. Swing” doing some of her best singing created quite a dramatic scenario. And the fans loved it.

Many critics point to Mildred and Red’s best work together on the album 1937 album Smoke Dreams. (re-released in 1999) The sound is a critical departure from big band stylings and more forward looking, as most of Red and Mildred’s work would veer toward. Originally released on Songbirds Records, the label’s web site includes a review by Jeff Austin. He writes;

“The Red Norvo Orchestra with Mildred Bailey had an unmistakable sound, with Bailey’s feather-light vocals paralleled by the delicacy and grace of Norvo’s xylophone, all couched in light, ever-swinging arrangements by the likes of Eddie Sauter. The title track, ‘Smoke Dreams,’ epitomizes what made Bailey/Norvo different than anyone else. Legend very credibly has it that, subsequent to Sauter’s being the object of a Bailey rage, he fashioned for her an arrangement that would be any other singer’s worst nightmare, riddled with ear-bending dissonance that might have permanently traumatized most other lady band singers. Undaunted, Bailey sails serenely through the din—and one is left wondering what other band (save, perhaps, for Stan Kenton ten years later) might have attempted a chart so avant-garde.”

Although the couple was successful, by the late 1930’s Mildred’s weight had become such a problem that she was kept more and more from public appearances. Along with the weight came problems with diabetes. This may have been part of her Native American heritage (Native Americans and Alaska Natives have a greater chance of having diabetes than any other US ethnic group according to the CDC). She had always had wild mood swings, but now she was more and more depressed. This was a time in her life that would have been incredibly bittersweet. She and Norvo divorced in the late 1930s (though remained friends and worked together on several recordings). She would also have two more number one hits during this period. In May of 1938 Red Norvo and His Orchestra with Mildred Bailey would have a chart-topper on the Hit Parade chart with the song “Please Be Kind”. In June of the same year they would also have a number one hit with “Says My Heart” Mildred’s final number one hit would be on Benny Goodman and His Orchestra’s 1940 song “Darn That Dream”.

She continued to take solace in food. Medical specialists-in fact most citizens today- know that there is a dangerous correlation between weight and diabetes. It wasn’t well known before the 1960s. Top that off with depression and it becomes an even more serious life-threatening condition. Today we would recognize Mildred Bailey as having an eating disorder that could be treated, alongside her mood swings. At the time many of her friends felt sorry for her and her inability to lose weight, while others simply blamed her condition on her own gluttony. According to her best friend, jazz singer Lee Wiley, Bailey suddenly threw herself on the floor just after Wiley said goodbye and was leaving her apartment one day.

“By God, I really talked her into living, because she apparently wanted to be dead,” Wiley said. “Well, what I did was to use some of her own language. I said, `Mildred! Now get your ass off that floor! Or something like that. And do you know that pretty soon a smile came over her face, and she got up?”

Yet she would again turn to food for comfort. The only other comfort she found was in her two dachshunds’

Her working relationship with Norvo lasted until 1944 when she retired because of her ongoing health problems. She continued to make sporadic appearances and in 1947 she performed to a sold-out audience at Carnegie Hall. Her health continued to deteriorate and along with the diabetes came something she’d never achieved while she was well. She became dangerously thin and frail. Not only was she very ill, she was broke and living in poverty in Upstate New York, Old friends like Bing Crosby paid her back for starting his career and supporting her during her final years. Those friends she’d picked up along the way also came to her aid, including Frank Sinatra who she’d dueted with in her later years. In fact it was an appearance on Bing Crosby’s radio show (her final appearance) that covered her mortgage payment in late 1951.

Finally on December 12, 1951 in Poughkeepsie, New York, at age 48 Mildred Bailey died of heart failure, due chiefly to diabetes and the exertion put on her heart throughout her adult life. Her death had not been a dramatic tragedy. Instead it was a long, drawn out affair that was precipitated by years of ill health. She was no longer in the public eye by the time she died, and although swing was in its final years her early contributions to be-bop weren’t yet recognized. So we’re still left with the unanswered question: why is Mildred Bailey forgotten?. Every 20 years or so jazz critics and enthusiasts ask the same question. The last period of interest in Mildred Bailey to ask the question came when Columbia Records released their complete recordings box set in 2001. That means we’re headed toward the same interest in Mildred Bailey and being stupefied why she is so forgotten is due within the next couple of years. I say take a listen NOW.

According to her official biography Mildred Bailey was inducted into the Big Band and Jazz Hall of Fame in 1989. Her contributions to jazz were commemorated by a United States Postal Stamp was issued in 1994. In 2012, the Coeur d’Alene Nation introduced a resolution honoring Bailey to the Idaho state legislature. They were seeking acknowledgement of the singer’s Coeur d’Alene ancestry as well as to promote her induction to the Jazz at Lincoln Center Hall of Fame in New York City. The resolution was adopted by The National Congress of American Indians. She has not yet been inducted into the Jazz at Lincoln Center Hall of Fame.

-Dennis R. White. Sources: Scott Yanow “Jazz on Film” (Backbeat Books, 2004); Catherine Bainbridge & Alfonso Maiorana “RUMBLE: The Indians Who Rocked the World” [film] (Kino Lorber 2017); “Mildred Bailey, American Singer” www.britannica.com/biography/Mildred-Bailey (retrieved February 14, 2018); “Mildred Bailey”www.biography.yourdictionary.com/mildred-bailey (retrieved February 13, 2018); Murray Horvitz “Mildred Bailey: That Rockin’ Chair Lady” (NPR, August 1, 2001); Owen McNally “Unforgettable Mildred Bailey Somehow Forgotten” (Hartford Courant, March 18, 2001); “Bailey Discography” www.slipcue.com/music/jazz/artists/mildredbailey.html (retrieved February 12. 2018); Michael Steinman “Who Erased Mildred Bailey?” (Jazz Lives, December 27, 2009); Gary Giddins “Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams-The Early Years, 1903-1940 (Brown & Little, 2001); Dennis Zotigh, “Meet Native America: Paulette E. Jordan, Idaho House Representative” (National Museum of the American Indian, 19 December 2014 retrieved February 12, 2018); Gary Giddins “Mrs. Swing” (The Village Voice, June 6, 2000); “Native Americans with Diabetes (Center for Disease Control and Prevention retrieved February 14, 2018); Jim Kershner “Coeur d’Alene Tribe celebrates jazz great’s reservation roots” (The Spokeman-Review lSpokane] April 1 2012);