J.J. Cale’s debut LP sounds as if it were recorded while the leader was on the verge of nodding off to sleep. Even though Naturally is a party album, a driving album, a sex album, a crying album, a mourning album, everything on it sounds muted, swaddled in fluffy blankets, as intimate as pillow talk. The record established from the get-go that ain’t nobody as laid-back as Tulsa, Oklahoma’s J.J. Cale, and ain’t nobody ever leveraged that posture to such sublime songs which somehow achieved commercial success—mostly in the hands of other artists (Er*c Clapt*n, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Johnny Cash, et al.).

Now, Cale was relatively old for an artist making his debut full-length (32), but that’s fitting when you take into account the man’s proclivity for doing things unhurriedly. The advantage to this is, Cale’s music burst into the world fully formed and honed to perfection. Naturally proffered all of J.J.’s styles and tics in one 12-song, 33-minute platter, and he spent the ensuing 40-plus years further polishing these modes (country, bluegrass, jazz, blues, and rockabilly, with sly nods to funk). But for many fans, Naturally remains Cale’s peak.

“Call Me The Breeze”—Cale’s first song on his first album—could be his definitive work, something that rarely happens in the music world. In it, J.J.’s spindly, rapid blues-guitar calligraphy wreathes the metronomic drum-machine beats, like Canned Heat in mechanized-mantra mode. It could be classified as “hick motorik,” as one writer for The Stranger put it in a 2009 feature on Cale. Even Cale’s driving songs choogle at a relatively slack pace. This friction-free, country-rock ramble was covered/homaged by Lynyrd Skynyrd, Johnny Cash, Spiritualized, Bobby Bare, and others.

Cale’s blues songs don’t seem very brutal, but rather something with which he handles with a minimum of fuss. Nevertheless, his sentiment seems genuine and the spare architecture of tracks such as “Call The Doctor,” “Don’t Go To Strangers,” and “Crying Eyes” convey a light gravitas that appealed to Spacemen 3 and Spiritualized, among many others. Cale’s intimate, gruff vocal style makes every word seem confidential and crucial. Even as he sounds as if he’s a second away from napping, Cale rivets on these blues tunes with his hushed, sandpapery tones. You can hear this to stunning effect on the unlikely single “Magnolia,” a spare, dewy ballad of exquisite beauty. The song is as evanescent as a teardrop, with Cale’s voice so full of regret it can hardly attain audibility.

But Naturally shows that Cale can also go jaunty and celebratory, too, as he does on the Dr. John-like “Woman I Love,” “Bringing It Back,” and “Nowhere To Run,” Cale’s idea of a rowdy Rolling Stones rocker, but still as laid-back as a yogi after a cup of camomile tea. And then there’s “After Midnight,” a subdued party jam that Clapt*n made famous even before J.J.’s album dropped. The subliminal funk of “After Midnight”— thanks largely to Norbert Putnam’s bass, Chuck Browning’s drums, and David Briggs’ piano—turns this classic into a boudoir-friendly slow-burner. (Grateful Dead comrade Merl Saunders covered it on Fire Up. You can read a review of that album here.)

Now let us reflect upon “Crazy Mama,” Cale’s only Top 40 hit and perhaps my fave song by him. From today’s perspective, it seems like a miracle that a tune as minimal and unobtrusive as this would chart, but those were different times. Even mainstream ears had the capacity to cherish music with subtlety in 1972. Despite its hedonistic title, “Crazy Mama” is prime hammock-lazing blues rock, with a slide-guitar solo by Mac Gayden that embodies libidinal ache as articulately as anything I’ve heard in my long life. “Crazy Mama” exemplifies the less-is-more ethos in rock.

Some artists try strenuously to reinvent themselves with every new release. Cale was completely at ease doing his own thing, with minor tweaks, decade after decade. Like the protagonist in “Call Me the Breeze,” Cale “[kept] blowing down the road… Ain’t no change in the weather/Ain’t no change in me.” So gloriously chill, that man and his music were, and the peacefulness that emanates from the latter is priceless. -Buckley Mayfield

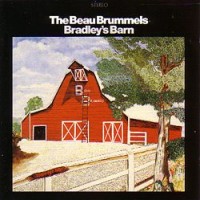

1. Bradley’s Barn Beau Brummels (1968) This release by undervalued San Francisco folk rockers, which arrived in stores just a few short weeks after Sweetheart of the Rodeo, is in some ways more successful than its competition. Much of this can be attributed to Sal Valentino’s gritty vocals and the impeccable picking of some ace Nashville sessioneers.

1. Bradley’s Barn Beau Brummels (1968) This release by undervalued San Francisco folk rockers, which arrived in stores just a few short weeks after Sweetheart of the Rodeo, is in some ways more successful than its competition. Much of this can be attributed to Sal Valentino’s gritty vocals and the impeccable picking of some ace Nashville sessioneers. 2. Goose Creek Symphony Established 1970 (1970) On their debut album, this Arizona outfit conveys a laid-back and goofy stoner vibe, which somewhat belies its virtuosic musicianship. Its side two opener, “Talk About Goose Creek and Other Important Places”, is one of country rock’s great psychedelic rave-ups.

2. Goose Creek Symphony Established 1970 (1970) On their debut album, this Arizona outfit conveys a laid-back and goofy stoner vibe, which somewhat belies its virtuosic musicianship. Its side two opener, “Talk About Goose Creek and Other Important Places”, is one of country rock’s great psychedelic rave-ups. 3. Grateful Dead American Beauty (1970) Which Grateful Dead album most typifies country rock is open to debate; clearly, it’s a toss-up between Workingman’s Dead and their next album, American Beauty. But in the end the latter achieves this distinction, if only by a slim margin. Featuring Jerry Garcia’s sparkling pedal steel guitar and some of the band’s best ever harmonies, the Dead would never sound this great in the studio again.

3. Grateful Dead American Beauty (1970) Which Grateful Dead album most typifies country rock is open to debate; clearly, it’s a toss-up between Workingman’s Dead and their next album, American Beauty. But in the end the latter achieves this distinction, if only by a slim margin. Featuring Jerry Garcia’s sparkling pedal steel guitar and some of the band’s best ever harmonies, the Dead would never sound this great in the studio again. 4. Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen Lost in the Ozone (1971) Looking back almost as much as it looked forward, this raucous album introduced elements of rockabilly and boogie-woogie into the country rock mix. Commander Cody would record some more great albums, but this remains his definitive statement.

4. Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen Lost in the Ozone (1971) Looking back almost as much as it looked forward, this raucous album introduced elements of rockabilly and boogie-woogie into the country rock mix. Commander Cody would record some more great albums, but this remains his definitive statement. 5. Michael Nesmith And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’ (1972) The Monkees’ hippest member recorded some of the best music in the country rock canon. But this minimalist outing, which features a rendition of “Different Drum” that’s superior to Linda Ronstadt’s version, is a true standout.

5. Michael Nesmith And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’ (1972) The Monkees’ hippest member recorded some of the best music in the country rock canon. But this minimalist outing, which features a rendition of “Different Drum” that’s superior to Linda Ronstadt’s version, is a true standout.