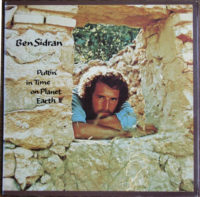

One wonders how a nerdy-looking, non-famous white keyboardist/singer convinced legends such as Miles Davis drummer Tony Williams, James Brown drummer Clyde Stubblefield, and session bassist Phil Upchurch of Rotary Connection and Chess/Cadet Records fame to back him on his third album, Puttin’ In Time On Planet Earth. Granted, Ben Sidran had co-written Steve Miller Band’s 1969 “Lady Madonna”-biting hit “Space Cowboy,” but still. You wouldn’t think a guy like this would have that kind of clout. Maybe Sidran simply charmed them into the fold, and coaxed Blue Thumb Records to compensate them handsomely? Whatever the case, praise your deity of choice that these cats somehow gathered to lay down this understated gem.

I’ve heard five Ben Sidran albums, and Puttin’ In Time On Planet Earth is the best. Now, the opener, “Full Compass” (which Upchurch wrote), a 39-second burst of flamboyant, Mahavishnu Orchestra-like fusion, is a red herring. But on the next track, “Play The Piano,” Sidran’s true nature emerges. It flaunts Sidran’s hip, Mose Allison-esque vocals that express how doing the thing that the title says is salvation. Sidran tickles out wonderful cascades of chords on the far right side of a grand piano while Upchurch and Stubblefield lift the rhythm from Prime Mates’ “Hot Tamales,” one of the greatest Latin/New Orleans funk songs ever. Your ears will do somersaults of joy. The striding blues jazz of “Have You Heard The News” exudes that irresistible Mose bonhomie and is boosted by the deft Mr. Williams on drums.

“Face Your Fears” features old Sidran buddy Steve Miller on acoustic guitar. It’s an inspirational jazz-pop song with Frank Rosolino on trombone and Sidran on Mellotron bringing new tones to the record, and it really soars in the second half thanks to Miller’s wonderfully warped electric-guitar solo and Tim Davis’ blissful backing vocals. “Walking With The Blues” is actually more dulcet smooth jazz than anything that sounds like Howlin’ Wolf. Here, Sidran sings in his most comforting, confidential tones as Bill Perkins exhales sultry, sinuous tenor sax solos. It’s quite precious.

As fine as all of this has been, Planet Earth really peaks on the last two tracks. I’ll be damned if the title track doesn’t share the same rhythm as that B-boy favorite, Can’s “Vitamin C.” Coincidence? I hope not. I love the idea of Clyde Stubblefield paying homage to Jaki Liebezeit. Upchurch lends crucial wah-wah guitar to this very classy approximation of blaxploitation-flick funk, while Sidran peels off keyboard runs that evoke Deodato circa “Also Sprach Zarathustra (2001)”.

Even better is “Now I Live (And Now My Life Is Done).” An ultra-slinky groove snakes with guile as Sidran vamps with enough verve to make Donald Fagen green with envy while guitarist Curley Cooke is on crystalline form, somewhere between George Benson and Pat Martino. Sidran’s use of bells and boinger percussion toy really add spine-tingles to this surreptitiously funky song. Throughout, Sidran recites an existentialist poem written by doomed 16th-century prisoner Chidiock Tichborne, who was executed for plotting to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I. Crazy backstory, right? This is simply one of the most sublime tracks I’ve ever heard, regardless of genre, and alone worth the price of admission, and then some. -Buckley Mayfield