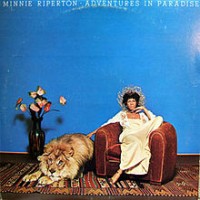

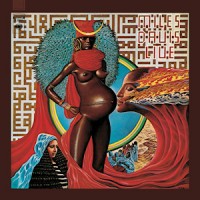

A modest album after some initial direct hits, Minnie was one of those up and coming R&B divas set to rival Aretha Franklin. After losing Stevie Wonder as super-producer however, this ’75 release instead opted for an even softer and smoother production, bringing it into the fold of Quiet Storm, the pristine music reflecting the promise of Black middle-class quality of life that was expected to stick around.

The entirety of the album isn’t made up of slow-jams, however… “When It Comes Down To It” has some popping bass lines and sharp instrumental work, while “Minnie’s Lament” showcases real signs of life vocally on top of, what seems to me, like a Xenakis “Rebonds A” sort of drum loop. Really! It’s no wonder Quiet Storm and sophisticated R&B are the next forms up for assimilation by our current musical underground. On one level, the hippest kids are more empathic than ever before and are less likely to dismiss it for classy connotations, and on another, the form is still ripe for mining outside of Hip Hop. It seems only natural that people like Sade and Minnie are new points of reference for genre-appropriating youth. This stuff is reactionary socially and at times, it’s otherworldly sounding.

But how about at the time of release? Of course this was an important album to those whose young lives were being enriched by hopes of a better home and life, an opportunity to raise a family, more cosmopolitan integration. That’s what makes this release so beautiful. It’s an album about love on deeper levels. The most recognizable track drifting through Adult Contemporary stations could be “Inside My Love,” which should be noted, isn’t about sex…“will you come inside me / do you wanna ride inside my love?” But to get back to Black upward mobility, Minnie’s popular album track for radio play, “Love and it’s Glory,” was never released as a single. Yet it had massive air play and it’s message bounded out:

It’s a lonely world my children

You’ve got to do the best you can

If you’ve found a chance to love

You’d better grab it any way you can -Wade