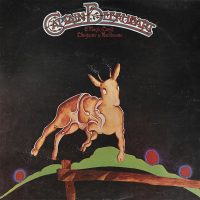

For decades I avoided Bluejeans & Moonbeams, because conventional wisdom and consensus opinion deemed it one of his worst works and an embarrassing stab at commercial success. (Spoiler alert: The album flopped with the public and critics.) Perhaps the former assertion is true, but when you’re dealing with an artist on the exalted level of Don Van Vliet, that shouldn’t be a deal-breaker. As for the second assertion, yes, B&M sounds relatively accessible when compared to Beefheart’s other releases—save for the equally reviled Unconditionally Guaranteed. However, this is still Beefheart, a musician incapable of making a record without something sounding interesting. And therefore I am going out on a withered limb and championing B&M… albeit with reservations.

One thing that makes this album different from most of Beefheart’s others is a new lineup that lacked a musical director who could translate the untrained band leader’s ideas into chords, notes, etc. Consequently, B&M‘s songs are much less complicated than usual for a Beefheart work. Nevertheless, side one is filled with good-to-great songs that may not tilt the music world off its axis like Safe As Milk, Trout Mask Replica, or Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller), but still go to some fascinating places and hit some familiar sweet spots.

B&M kicks off in grand style with “Party Of Special Things To Do,” a funky blues number that appealed enough to that learned rock scholar Jack White for the White Stripes to cover it on a 2001 Sub Pop 45. There are some serious Dr. John-like swamp vibes here, and Van Vliet’s in his trademark gruff Howlin’ Wolf vocal mode. The cover of JJ Cale’s “Same Old Blues” could never equal the original’s archetypal laid-back blues funk, but kudos to Van Vliet and company for attempting to do so.

B&M peaks with “Observatory Crest,” probably the most beautiful melody Beefheart’s written (with help from Mothers Of Invention/Fraternity Of Man guitarist Elliot Ingber). This dreamy, spacey tune was covered by Mercury Rev and the Swedish band Whipped Cream, and if you can’t luxuriate in the spectral shimmer of this tune, you need to make some major aesthetic adjustments. Side one closes with the funky blues-rock of “Pompadour Swamp,” which harks back to Beefheart’s The Spotlight Kid, but sounds not as menacing or off-kilter. “Captains Holiday” is a laggard, Stones-y blues-funk jam without any input from Beefheart—hence, the title.

The quality drops substantially on side two, unfortunately. “Rock ‘N’ Roll’s Evil Doll” has all the charm of a post-Jim Morrison Doors song, a C-plus blues-rock bump and grind of which Van Vliet and company seem to be going through the motions, while “Further Than We’ve Gone” comes off as a blundering yet snoozy “soul” ballad in which Van Vliet sounds unconvincing and everyone else sounds bored. “Twist Ah Luck” emulates a mid-level Rolling Stones chugger with a straight face, a move that should be beneath Beefheart. But dude was in a slump, as “Bluejeans & Moonbeams” conclusively proves; it’s Beefheart at his sappiest. Try not to cringe at this attempt at tender balladeering, corny orchestrations, and slide-guitar soloing—I dare you. This might the second lowest point in the Beefheart canon, after “This Is The Day.”

Still and all, Bluejeans And Moonbeams has two bona-fide classics (“Observatory Crest” and “Party Of Special Things To Do”) and enough flashes of deceptively dirty funk to be worth your time, if you can find it on the cheap. And at least it’s better than Unconditionally Guaranteed. -Buckley Mayfield