Considering that this kind of music was released in 1968 is amazing, but even more amazing is that it still kicks the ass of every other electro-pop-band, save perhaps Kraftwerk. The oscillators flow wildly, the drums lay mindnumbing beats and the lyrics, maybe hippie-esque considering the day, somehow seem ageless still. And it’s unbelievably catchy, like in a pop way. I could tell a funny tale about Syd Barrett finding a Close Encounters of the Third Kind-style alien mothership wrecked somewhere in the forest and going all circuit breaking on the mushrooms, but I won’t. Pioneering and reigning still. All hail the whirly-bird! –Tuukka

Considering that this kind of music was released in 1968 is amazing, but even more amazing is that it still kicks the ass of every other electro-pop-band, save perhaps Kraftwerk. The oscillators flow wildly, the drums lay mindnumbing beats and the lyrics, maybe hippie-esque considering the day, somehow seem ageless still. And it’s unbelievably catchy, like in a pop way. I could tell a funny tale about Syd Barrett finding a Close Encounters of the Third Kind-style alien mothership wrecked somewhere in the forest and going all circuit breaking on the mushrooms, but I won’t. Pioneering and reigning still. All hail the whirly-bird! –Tuukka

Psych and Prog

Love “Da Capo” (1966)

Inhabiting a strange dimension between the Byrds-meets-the-Rolling Stones bluster of their debut LP and the psychedelic mariachi sprawl of Forever Changes, Love’s Da Capo is a transitional album in every sense of the word. Taken together, the six songs that constitute its “Side A Suite” represent some of the best music of the ’60s, making it all the more painful that Side B represents one of its biggest let-downs. On the opening track, “Stephanie Knows Who”, Arthur Lee not only comes into his own, but also establishes himself as one of the most unique and expressive lead vocalists of his generation. There are probably Hallmark cards that are less maudlin and sappy than the MacLean-penned second track, “Orange Skies”, but somehow, miraculously, the band’s tight playing and Lee’s delivery elevate it to greatness. The loungey “¡Que Vida!” is a bit of fluff, but it swings like a Sunset Strip hipster. The mighty “Seven and Seven Is”, one of the few Love songs that ever charted, has been reproduced on garage compilations many times over, but hearing it here in its natural environment reveals what a massive artistic achievement it really is. Loud, fast, and intense, it could only end with the famous nuclear blast of its coda. Thankfully, respite is provided in the form of the acoustic and introspective gem, “The Castle”. Finally comes the mystical masterpiece, “She Comes in Colors”, a song so great that even the Hooters couldn’t ruin it when they covered it almost two decades later. But then there’s the meandering blues-jam, “Revelation”. Taking up that whole flipside and clocking in at almost 20 minutes, it’s perhaps unfairly maligned. On its own merits it’s not terrible, but here it only detracts from the focused brilliance of what came before, and it wears out its welcome quickly. Had wiser council prevailed at Elektra, Da Capo would take its place among such giants such as Are You Experienced?, Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and even its creators’ own definitive artistic statement, Forever Changes. But instead this sophomore effort has to settle for “almost great” status. However, it is still essential. – Richard

Inhabiting a strange dimension between the Byrds-meets-the-Rolling Stones bluster of their debut LP and the psychedelic mariachi sprawl of Forever Changes, Love’s Da Capo is a transitional album in every sense of the word. Taken together, the six songs that constitute its “Side A Suite” represent some of the best music of the ’60s, making it all the more painful that Side B represents one of its biggest let-downs. On the opening track, “Stephanie Knows Who”, Arthur Lee not only comes into his own, but also establishes himself as one of the most unique and expressive lead vocalists of his generation. There are probably Hallmark cards that are less maudlin and sappy than the MacLean-penned second track, “Orange Skies”, but somehow, miraculously, the band’s tight playing and Lee’s delivery elevate it to greatness. The loungey “¡Que Vida!” is a bit of fluff, but it swings like a Sunset Strip hipster. The mighty “Seven and Seven Is”, one of the few Love songs that ever charted, has been reproduced on garage compilations many times over, but hearing it here in its natural environment reveals what a massive artistic achievement it really is. Loud, fast, and intense, it could only end with the famous nuclear blast of its coda. Thankfully, respite is provided in the form of the acoustic and introspective gem, “The Castle”. Finally comes the mystical masterpiece, “She Comes in Colors”, a song so great that even the Hooters couldn’t ruin it when they covered it almost two decades later. But then there’s the meandering blues-jam, “Revelation”. Taking up that whole flipside and clocking in at almost 20 minutes, it’s perhaps unfairly maligned. On its own merits it’s not terrible, but here it only detracts from the focused brilliance of what came before, and it wears out its welcome quickly. Had wiser council prevailed at Elektra, Da Capo would take its place among such giants such as Are You Experienced?, Piper at the Gates of Dawn, and even its creators’ own definitive artistic statement, Forever Changes. But instead this sophomore effort has to settle for “almost great” status. However, it is still essential. – Richard

Beyond Nuggets:

A Guide to ’60s Ephemera

In 1972 Elektra Records’ Jac Holzman asked future Patti Smith Group guitarist and bassist Lenny Kay to compile what was a essentially a glorified mixed tape, resulting in Nuggets: Original Artyfacts of the First Psychedelic Era. This release became synonymous with the term “Garage Rock”, but this designation is not entirely accurate. Though rough and tumble staples like the 13th Floor Elevators and the Seeds are represented, more poppy-sounding bands like the Mojo Men, Sagittarius (featuring Glenn Campbell on vocals), and a host of other acts—some of whom were nowhere near a suburban garage when they cut these sides — are there too. Nuggets’ legacy is not so much its innovative (re)packaging of near hits, but its role in defining an aesthetic and its establishing of multiple genres and sub-genres: acid rock, power pop, sunshine pop, imitation Merseybeat, Dylan copycats, blue-eyed soul, even early Latino-rock — they’re all here along with more that send rock critics reaching for their thesauruses and record collectors scrambling for their paypal accounts. Perhaps neither Kaye nor Holzman knew the long-term ramifications of their Frankenstenian experiment. Indeed, the monster they created essentially spawned a whole industry, that of the Esoteric 60’s Music Compilation. It’s an industry that refuses to die, even almost 40 years later. Exploring this brave new world can be a daunting task. Here then is a quick guide to some logical starting points:

1. Pebbles – Conceived and created in Australia only a few years after the original Nuggets, this series focused on more raw and obscure (though not entirely unknown) acts from the US. Numerous volumes and offshoot series of widely varying quality proliferated through the 70’s and 80’s, but volumes 1-6 are pretty darn solid.

1. Pebbles – Conceived and created in Australia only a few years after the original Nuggets, this series focused on more raw and obscure (though not entirely unknown) acts from the US. Numerous volumes and offshoot series of widely varying quality proliferated through the 70’s and 80’s, but volumes 1-6 are pretty darn solid.

2. Back From The Grave – One of the few series worthy of the “60’s Garage Rock” classification, the US bands represented here are young, fast, raw, and sometimes very poorly recorded, which undoubtedly adds to its authenticity.

2. Back From The Grave – One of the few series worthy of the “60’s Garage Rock” classification, the US bands represented here are young, fast, raw, and sometimes very poorly recorded, which undoubtedly adds to its authenticity.

3. Acid Visions – Regional garage and psych compilations are very common. This one focuses on the Lone Star State, which produced a surprisingly diverse and consistently high quality array of sounds in the ’60s. The third and final volume focuses on female artists, a very underrepresented demographic in this male-dominated realm.

3. Acid Visions – Regional garage and psych compilations are very common. This one focuses on the Lone Star State, which produced a surprisingly diverse and consistently high quality array of sounds in the ’60s. The third and final volume focuses on female artists, a very underrepresented demographic in this male-dominated realm.

4. English Freakbeat – Since suburban two-car garages are not as common in England, perhaps it was inevitable that a moniker for similar music from the British Isles would be invented, and “Freakbeat” seems just as apt as any. Though the bands on these five LPs share many commonalities with their American garage brethren, a rawer and more purist blues sensibility often dominates.

4. English Freakbeat – Since suburban two-car garages are not as common in England, perhaps it was inevitable that a moniker for similar music from the British Isles would be invented, and “Freakbeat” seems just as apt as any. Though the bands on these five LPs share many commonalities with their American garage brethren, a rawer and more purist blues sensibility often dominates.

5. Rubble – While this Anglocentric series covers the Freakbeat sound like the series mentioned above, its emphasis is on the more cerebral and whimsical Psych-Pop of the late ’60s British and European scenes. Though spotty at times, many installments in this twenty volume series have numerous great tracks.

5. Rubble – While this Anglocentric series covers the Freakbeat sound like the series mentioned above, its emphasis is on the more cerebral and whimsical Psych-Pop of the late ’60s British and European scenes. Though spotty at times, many installments in this twenty volume series have numerous great tracks.

Further listening: One would think that by this point everything worthwhile has been unearthed, but the excavation continues. As unknown sides from the US and British scenes of the 60’s become scarcer, collectors are looking to more unexplored caches. Private pressings, underground Prog Rock, and Global Garage Rock have been the subject of many comps as of late. Cambodian Rocks delves into a thriving Asian scene that was tragically quashed when the Khmer Rouge took power. Love, Peace, and Poetry, a series still in progress, spans the globe to bring listeners impossibly rare pysch from the ’60s and ’70s. —Richard P

Are we forgetting your favorite series? Share your comments here:

Camel “The Snow Goose” (1975)

The Snow Goose is an essential experience, evocative and emotional, ambitious in it’s concept and execution, but accessible as well. The band manage to sustain an entirely instrumental album by filling it with brief, memorable pieces, carried by their always measured performances. While most of the album is devoted to the familiar Camel sound, they are joined in places by a small woodwinds group, expanding the scope of the music. Although you’ll want to leave the needle in place once you drop it, a few especially awesome moments are worth mentioning in particular, such as the multi-dimensional “Rhayader Goes To Town”, “The Snow Goose” which features some tender, spine-tingling guitar phrases, the duo of “Preparation”, with it’s foreboding sequencer pattern, and it’s haunting, slow-boiling partner in “Dunkirk”. But this is a complete, constantly unfolding album that should be heard with the lights down low, brew of choice in hand, the world of The Goose swooping into your listening room and filling the next 40 minutes with it’s sublime sounds. –Ben

The Snow Goose is an essential experience, evocative and emotional, ambitious in it’s concept and execution, but accessible as well. The band manage to sustain an entirely instrumental album by filling it with brief, memorable pieces, carried by their always measured performances. While most of the album is devoted to the familiar Camel sound, they are joined in places by a small woodwinds group, expanding the scope of the music. Although you’ll want to leave the needle in place once you drop it, a few especially awesome moments are worth mentioning in particular, such as the multi-dimensional “Rhayader Goes To Town”, “The Snow Goose” which features some tender, spine-tingling guitar phrases, the duo of “Preparation”, with it’s foreboding sequencer pattern, and it’s haunting, slow-boiling partner in “Dunkirk”. But this is a complete, constantly unfolding album that should be heard with the lights down low, brew of choice in hand, the world of The Goose swooping into your listening room and filling the next 40 minutes with it’s sublime sounds. –Ben

The Incredible String Band “The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion” (1967)

Yes, I think this is even better than The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. The difference is while that record gets its strength from its total weirdness — it meanders in the best sense — this one has actual songs: great, great songs that will move you, make you laugh and make you think. “First Girl I Loved” alone is enough to get you seeking out this record, but add to that the prescient sarcasm of “Back In The 1960s” (which foresees the death of the hippie ideal before it had even begun), the Wind In The Willows on acid of “Little Cloud” and “The Hedgehog Song” (The Archbishop of Canterbury’s fave ISB number!) and the simply beautiful “Painting Box”. Plus I love the way Williamson sings. For those of you who wonder what “The Fool On The Hill” would have been liked if Lennon had written it. –Brad

Yes, I think this is even better than The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. The difference is while that record gets its strength from its total weirdness — it meanders in the best sense — this one has actual songs: great, great songs that will move you, make you laugh and make you think. “First Girl I Loved” alone is enough to get you seeking out this record, but add to that the prescient sarcasm of “Back In The 1960s” (which foresees the death of the hippie ideal before it had even begun), the Wind In The Willows on acid of “Little Cloud” and “The Hedgehog Song” (The Archbishop of Canterbury’s fave ISB number!) and the simply beautiful “Painting Box”. Plus I love the way Williamson sings. For those of you who wonder what “The Fool On The Hill” would have been liked if Lennon had written it. –Brad

Muddy Waters “Electric Mud” (1968)

This may be the most polarizing album ever to come out of the Chess empire (unless that Rotary Connection Christmas album really drives you batty); it’s telling that they chose to release this on the more daring Cadet Concept subsidiary. It’s funny to think that this album was intended to update Muddy Waters’ image to appeal to the younger people and, 42 years on, that’s exactly what it did for me, who currently fits the original demographic they were after: I have no quarrel with traditional blues, I even enjoy it when the mood strikes me, but this is the only Muddy Waters album that I beat the proverbial door down to acquire. And this album is ferocious! There’s no session information given but I would have to imagine that it’s the usual Chess/Cadet session crew backing him up. The bass rumbles along louder than I’ve ever heard John Paul Jones’ or John Entwistle’s. The drums, in particular the bass drum, are louder than those in any psych group I can think of other than maybe the Move. The most surprising aspect may be that, despite the fact that Muddy reportedly hated this album with a passion, his electric guitar playing is phenonmenal. I suppose this is expected from a great bluseman, but he also knows how to use its new-found volume and distortion to great effect. He growls through each monster track, achieving what Jimi Hendrix was ly after in his formative days. As it is a late 60s Cadet Concept album, the ace in the hole is the arrangement, this time from the great Charles Stepney, in the midst of arranging the hell out of those Rotary Connection and Ramsey Lewis albums (the latter along with Richard Evans). Stepney actually displays quite a bit of restraint here, with his patented complex string and brass parts lurking way in the background, the exception being when “She’s Alright” brilliantly morphs it’s coda into the string-laden bridge from “My Girl”.

This may be the most polarizing album ever to come out of the Chess empire (unless that Rotary Connection Christmas album really drives you batty); it’s telling that they chose to release this on the more daring Cadet Concept subsidiary. It’s funny to think that this album was intended to update Muddy Waters’ image to appeal to the younger people and, 42 years on, that’s exactly what it did for me, who currently fits the original demographic they were after: I have no quarrel with traditional blues, I even enjoy it when the mood strikes me, but this is the only Muddy Waters album that I beat the proverbial door down to acquire. And this album is ferocious! There’s no session information given but I would have to imagine that it’s the usual Chess/Cadet session crew backing him up. The bass rumbles along louder than I’ve ever heard John Paul Jones’ or John Entwistle’s. The drums, in particular the bass drum, are louder than those in any psych group I can think of other than maybe the Move. The most surprising aspect may be that, despite the fact that Muddy reportedly hated this album with a passion, his electric guitar playing is phenonmenal. I suppose this is expected from a great bluseman, but he also knows how to use its new-found volume and distortion to great effect. He growls through each monster track, achieving what Jimi Hendrix was ly after in his formative days. As it is a late 60s Cadet Concept album, the ace in the hole is the arrangement, this time from the great Charles Stepney, in the midst of arranging the hell out of those Rotary Connection and Ramsey Lewis albums (the latter along with Richard Evans). Stepney actually displays quite a bit of restraint here, with his patented complex string and brass parts lurking way in the background, the exception being when “She’s Alright” brilliantly morphs it’s coda into the string-laden bridge from “My Girl”.

Most blues purists decry this, which I suppose is understandable, but you have to admit that this is as convincing a psychedelic-blues album as anything Cream or Led Zeppelin could hope to come up with. Still underrated by most critics, this is truly a left-field masterpiece. –Mike

Caetano Veloso “Caetano Veloso” (1971)

Ironically enough, Caetano Veloso’s almost entirely English language album is one of the most misunderstood of his classic 60s/70s period amongst English-speaking audiences (first place goes to Araca Azul, but that one at least gives you fair warning of its polarizability by the Caetano-in-bikini cover). Recorded while in exile in London, the album marks a dramatic musical departure from his first 2 solo outings that he would continue to explore up through 1977 or thereabouts. I must confess I don’t know too many details of Caetano’s (or Gilberto Gil’s) exile in London. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity on the part of the British, though there was probably no reason why anyone there should’ve known who he was. Apparently some Traffic members were big fans, and even helped out on Gil’s sessions but if I were George Harrison or Twink or Jimmy Page or Bill Wyman or Jack Bruce or Marc Bolan or Mike Heron and someone told me that the leading light of Brazil’s new underground rock movement was in my midst, I would totally be over there asking if he wanted to go bowling or split an appetizer or something. Or if I was Jimmy Page, I would ask if I could steal his guitar line from “Irene”.

Ironically enough, Caetano Veloso’s almost entirely English language album is one of the most misunderstood of his classic 60s/70s period amongst English-speaking audiences (first place goes to Araca Azul, but that one at least gives you fair warning of its polarizability by the Caetano-in-bikini cover). Recorded while in exile in London, the album marks a dramatic musical departure from his first 2 solo outings that he would continue to explore up through 1977 or thereabouts. I must confess I don’t know too many details of Caetano’s (or Gilberto Gil’s) exile in London. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity on the part of the British, though there was probably no reason why anyone there should’ve known who he was. Apparently some Traffic members were big fans, and even helped out on Gil’s sessions but if I were George Harrison or Twink or Jimmy Page or Bill Wyman or Jack Bruce or Marc Bolan or Mike Heron and someone told me that the leading light of Brazil’s new underground rock movement was in my midst, I would totally be over there asking if he wanted to go bowling or split an appetizer or something. Or if I was Jimmy Page, I would ask if I could steal his guitar line from “Irene”.

One aspect of Veloso’s exile period is quite : he did NOT like it. The cover is amazing. Caetano looks like he’s 50, he’s cold, and you just told him a mildly offensive joke. One would assume this album is as bleak as Pink Moon but the first couple of songs might surprise you. “A Little More Blue” opens with a laidback, meandering acoustic figure that sounds a bit mellow but certainly not conducive to soul-bearing. The lyrics are about events that have made him sad, even though at the present moment “I feel a little more blue than then”. Along the way he peppers in references to his own exile and some truly vivid lyrics (“her dead mouth with red lipstick smiled”). An odd, dichotomous opener. “London, London” is for me the standout. And, oddly enough, it’s the jauntiest track, replete with playful flute like Donovan’s 67-era acoustic sides. It’s one of the most exquisitely beautiful songs I’ve ever heard concerning alienation, loneliness, and, above all, homesickness. In this respect, it can be seen as the post-traumatic counterpart to the desperate “Lost in the Paradise” from his previous album. And while I hold that song to be one of the best songs ever written, period, “London, London” offers the beautifully resigned flipside of that coin. And all this from a song whose refrain is “My eyes go looking for flying saucers in the skies”. Things start to get a bit darker with the more-produced “Maria Bethania”, a plea to his sister. “If You Hold a Stone” is an expanded, highly repetitve reworking of “Marinheiro So” from the previous album. I’m not going to pretend to know what he’s talking about here (even though it’s in English and he repeats it like 30 times) but I could listen to it all day long. The last song “Asa Branca” is the only Portuguese-language track on the album and as such it’s an emotionally powerful return to relatively familiar territory for Caetano. The song, written by Luiz Gonzaga and Humberto Teixeira, is about a native farmer (presumably) of Northeastern Brazil having to leave the land and his wife during one of the droughts that often occur in that part of the country because he is unable to make a living. At the end he promises to return. Amazingly, if you really try to live inside this album, you don’t really need to know Portugese to understand what this song is saying. A haunting, ethereal way to end perhaps the most personal album in Veloso’s storied career.

This album is notable for several reason. Firstly, it marks a dramatic change in musical direction for Veloso. I’ve never heard an album with a greater sense of space. There is a lot of silence on this album and it itself is utilized almost as an additional instrument, a “symphony of silence” (mental copyright) if you will. His first solo album was lush and sprightly and full of subtle sonic experimentation. His second album made the sonic experimentation much more explicit and combined this with a panoramic feeling that made that album at times feel tense and murky (not a bad thing in this case). This album does a dramatic about-face with its spare, acoustic lines, occasional bass-and-drum backing, and lyric-centric approach. This formula would reach full fruition on Transa and continue up until 1977’s African-influenced Bicho. The second notable aspect of this album is how well Veloso’s poetry translates into English. That’s no mean feat. Gil’s more awkward English makes his equivalent album difficult to decipher emotionally but Caetano’s only slightly accented English is perfectly suited to his prose that, though economical, are undeniably evocative and effective at relating emotional depth. Certainly not a place to start for Caetano Veloso, but you should try to find yourself here if you are willing to acquire more than 3 of his albums. –Mike

The United States of America (1968)

I first discovered this LP in a Capitol Hill thrift store in the mid-90’s, when it was still fairly easy to find such LP’s in thrift stores. Thumbing through the Broadway musical soundtracks and Herb Alpert LP’s, I came across a battered copy of this curiosity. Its cover suggested a bunch of M.I.T. graduate students performing research on how to be in a rock band, and the musical credits listed on the back were even more perplexing. The bassist played a fretless; there was no guitarist but there was an electric violin player. (And just what the hell was a “ring modulator” anyway?) I couldn’t tell how old the record was, but the hairstyles and packaging suggested about 1968 (I turned out to be right). The $3 sticker was enough incentive, so I bought it. Playing it when I got home, my reaction to its aural content was that of even more bafflement. It was a strange and shifting cacophony from start to finish: calliopes, pounding drums, tape loops, haunting ballads about clouds and deceased revolutionaries, Gregorian chants, chamber strings, Zappaesque satire, Salvation Army brass bands, and a barrage of otherworldly electronic bleeps and warbles. At first I wanted to throw it across the room, but within a few days it was all I was listening to and all I would listen to for the next month. We all know about these records, records that we happen upon by accident and which we initially don’t understand but which end up changing the very core of our being and defining our musical tastes. For these records, “love it or hate it” isn’t an apt descriptor. Like organ transplants, they are either violently rejected or they become a part of us. For me, The United States of America’s sole LP is one such record. –Richard

I first discovered this LP in a Capitol Hill thrift store in the mid-90’s, when it was still fairly easy to find such LP’s in thrift stores. Thumbing through the Broadway musical soundtracks and Herb Alpert LP’s, I came across a battered copy of this curiosity. Its cover suggested a bunch of M.I.T. graduate students performing research on how to be in a rock band, and the musical credits listed on the back were even more perplexing. The bassist played a fretless; there was no guitarist but there was an electric violin player. (And just what the hell was a “ring modulator” anyway?) I couldn’t tell how old the record was, but the hairstyles and packaging suggested about 1968 (I turned out to be right). The $3 sticker was enough incentive, so I bought it. Playing it when I got home, my reaction to its aural content was that of even more bafflement. It was a strange and shifting cacophony from start to finish: calliopes, pounding drums, tape loops, haunting ballads about clouds and deceased revolutionaries, Gregorian chants, chamber strings, Zappaesque satire, Salvation Army brass bands, and a barrage of otherworldly electronic bleeps and warbles. At first I wanted to throw it across the room, but within a few days it was all I was listening to and all I would listen to for the next month. We all know about these records, records that we happen upon by accident and which we initially don’t understand but which end up changing the very core of our being and defining our musical tastes. For these records, “love it or hate it” isn’t an apt descriptor. Like organ transplants, they are either violently rejected or they become a part of us. For me, The United States of America’s sole LP is one such record. –Richard

David Axelrod “Song of Innocence” (1968)

Trying to put a tag on the music of legendary producer David Axelrod is almost impossible as his music, especially [when] early offerings such as this, straddles so many genres. You get funk, jazz, classical and rock all thrown into the melting pot to create a rather unique sound that has had a large influence on many people. Nowhere has this been more apparent than in hip hop and trip hop where this LP has been heavily sampled. If you are a fan of those two genres prepare to hear a lot of familiar breaks when you hear this record for the first time. The LP itself was heavily influenced by the poetry of William Blake hence there is a dark brooding feel throughout and Axelrod uses layers of strings playing minor keys to obtain this mood. The drums and percussion drive the music on and there are some fantastic guitar breaks. –Jon

Trying to put a tag on the music of legendary producer David Axelrod is almost impossible as his music, especially [when] early offerings such as this, straddles so many genres. You get funk, jazz, classical and rock all thrown into the melting pot to create a rather unique sound that has had a large influence on many people. Nowhere has this been more apparent than in hip hop and trip hop where this LP has been heavily sampled. If you are a fan of those two genres prepare to hear a lot of familiar breaks when you hear this record for the first time. The LP itself was heavily influenced by the poetry of William Blake hence there is a dark brooding feel throughout and Axelrod uses layers of strings playing minor keys to obtain this mood. The drums and percussion drive the music on and there are some fantastic guitar breaks. –Jon

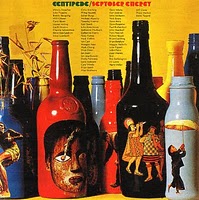

Centipede “Septober Energy” (1971)

This ominous double LP has been sitting there in my record collection since 1973. I don’t know why I haven’t played it for ages, I used to play it a lot. So, the first of October is an apt day to play and review Septober Energy. It is a project assembled by Keith Tippett and produced by Robert Fripp (both members of King Crimson at the time). These two gathered virtually the entire creative British music scene – a who-is-who of some 50 musicians, horns, brass, strings, singers, Alan Skidmore, Elton Dean, Ian Carr, Alan Skidmore, Paul Rutherford, John Marshall, Robert Wyatt, Ian MacDonald, Boz Burrell, Julie Driscoll (Tippett at the time of recording), just to name a few. The music sounds as if Tippett and Fripp were struggling to find a home for their jazzier, freer ideas which they couldn’t incorporate into the King Crimson concept.

This ominous double LP has been sitting there in my record collection since 1973. I don’t know why I haven’t played it for ages, I used to play it a lot. So, the first of October is an apt day to play and review Septober Energy. It is a project assembled by Keith Tippett and produced by Robert Fripp (both members of King Crimson at the time). These two gathered virtually the entire creative British music scene – a who-is-who of some 50 musicians, horns, brass, strings, singers, Alan Skidmore, Elton Dean, Ian Carr, Alan Skidmore, Paul Rutherford, John Marshall, Robert Wyatt, Ian MacDonald, Boz Burrell, Julie Driscoll (Tippett at the time of recording), just to name a few. The music sounds as if Tippett and Fripp were struggling to find a home for their jazzier, freer ideas which they couldn’t incorporate into the King Crimson concept.

There are moments of grandezza, pathos, Jazz-Rock passages, Free Jazz – both loud and aggressive and soft and gentle, Bolero-like crescendos, concert music, sheet music, smashing arrangements and orchestrations, all of it played live in the studio and simultaneously recorded. Of course, due to the concept, there are also passages which don’t succeed or which are too long – I’m thinking of the finale. Septober Energy has been put down as megalomania, usually from King Crimson fans. I don’t agree. It’s difficult music, certainly. You have to make an effort to follow the music. It might just not be your taste. But that doesn’t make it a flop. Septober Energy is like nothing else from the early seventies, it’s an important musical document from one of the most exiting musical phases in the twentieth century. I’m glad I re-discovered this album. It’s out on CD and should not be overlooked. –Yofriend

Grateful Dead “Grateful Dead” (1967)

The Dead were never a studio band, and their first record is even overlooked by the most ardent Deadheads. It’s easy to see why; here they sound more like a garage band: raw, loud, way fast, and with only one drummer! Recorded in LA, it’s rumored that the band cut these tracks in just a few hours while hopped up on Ritalin (an irony considering the superhuman attention span required for the long-winded jams of their later years). The opener, “The Golden Road…” sets the momentum for a series of short, bluesy, breakneck tempo numbers that don’t slow down until the beginning of Side Two: a cover of Bonnie Dobson’s post-apocalyptic “Where is everybody?” ballad, “Morning Dew”. But even here there’s a sense of visceral urgency that the band seldom recaptured on stage or off. The closing prison song cover, “Viola Lee Blues”, more closely resembles the exploratory and improvisational sound that would soon become their stock in trade, but with just enough sloppiness and dissonance to keep things interesting. From here, the Dead would inarguably record and perform some more great music while vocalist/organist Pigpen still had his liver, but never again with such reckless abandon. –Richard P

The Dead were never a studio band, and their first record is even overlooked by the most ardent Deadheads. It’s easy to see why; here they sound more like a garage band: raw, loud, way fast, and with only one drummer! Recorded in LA, it’s rumored that the band cut these tracks in just a few hours while hopped up on Ritalin (an irony considering the superhuman attention span required for the long-winded jams of their later years). The opener, “The Golden Road…” sets the momentum for a series of short, bluesy, breakneck tempo numbers that don’t slow down until the beginning of Side Two: a cover of Bonnie Dobson’s post-apocalyptic “Where is everybody?” ballad, “Morning Dew”. But even here there’s a sense of visceral urgency that the band seldom recaptured on stage or off. The closing prison song cover, “Viola Lee Blues”, more closely resembles the exploratory and improvisational sound that would soon become their stock in trade, but with just enough sloppiness and dissonance to keep things interesting. From here, the Dead would inarguably record and perform some more great music while vocalist/organist Pigpen still had his liver, but never again with such reckless abandon. –Richard P

The Kinks “The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society” (1968)

This album still grows on me every time I listen to it! In the title track the Kinks sing ‘God save Donald Duck, Vaudeville and Variety’ and in this collection they do their best to immortalise all kinds of things. If all the world’s music except for this album were suddenly to disappear the Kinks would single-handedly have preserved some simple but catchy pop tunes (“Johnny Thunder” and “Animal Farm”), Vaudeville (in the form of “Sitting By The Riverside”) and Music Hall (“All Of My Friends Were There”) as well as the Village Green. Quite an achievement. But they don’t stop there. They capture the sound of The Grateful Dead and Dylan on “Last Of The Steam-Powered Trains” and is that Hendrix I hear in “Big Sky”? Then there’s the darkly psychedelic “Wicked Annabella” and the latin “Monica”. They do their own take on the “Under My Thumb” Rolling Stones theme in “Starstruck” and the ridiculous in “Phenomenal Cat” (who sounds as if he’s all set to eat the equally ridiculous Donald D). Is there no end to their conserving? “Picture Book” and “People Take Pictures Of Each Other” make sure that our nearest and dearest aren’t forgotten. Rest assured – we’re in safe hands. Taken on their own, many of the songs are rather simple. But put together I believe they amount to an artistic masterpiece – a preserved musical and poetic patchwork of past and present, itself reflecting the patchwork of the countryside that is home to many a village green. –Jim

This album still grows on me every time I listen to it! In the title track the Kinks sing ‘God save Donald Duck, Vaudeville and Variety’ and in this collection they do their best to immortalise all kinds of things. If all the world’s music except for this album were suddenly to disappear the Kinks would single-handedly have preserved some simple but catchy pop tunes (“Johnny Thunder” and “Animal Farm”), Vaudeville (in the form of “Sitting By The Riverside”) and Music Hall (“All Of My Friends Were There”) as well as the Village Green. Quite an achievement. But they don’t stop there. They capture the sound of The Grateful Dead and Dylan on “Last Of The Steam-Powered Trains” and is that Hendrix I hear in “Big Sky”? Then there’s the darkly psychedelic “Wicked Annabella” and the latin “Monica”. They do their own take on the “Under My Thumb” Rolling Stones theme in “Starstruck” and the ridiculous in “Phenomenal Cat” (who sounds as if he’s all set to eat the equally ridiculous Donald D). Is there no end to their conserving? “Picture Book” and “People Take Pictures Of Each Other” make sure that our nearest and dearest aren’t forgotten. Rest assured – we’re in safe hands. Taken on their own, many of the songs are rather simple. But put together I believe they amount to an artistic masterpiece – a preserved musical and poetic patchwork of past and present, itself reflecting the patchwork of the countryside that is home to many a village green. –Jim