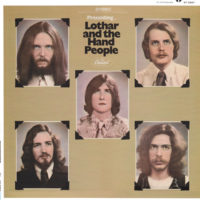

Look at that cover. The five members of Lothar And The People seem like the high-school students most likely to join a benign cult based on the plot of a ridiculous fantasy novel. Yet after they moved from Denver to New York City, the quirky quintet signed to Capitol Records… and the rest is cult-rock history.

LATHP cut two surprisingly good albums and then adios’d. But they had the distinction of being the first rock group to tour with synthesizers and one of the few to manipulate Theremins. These nerds had an air of gimmickry about them, but they also had talent. Their 1968 debut album, Presenting…, abounds with high-quality, Moog-enhanced novelty rock.

Produced by Robert Marguleff of the excellent synth duo Tonto’s Expanding Head Band (who later worked studio magic on Stevie Wonder’s best albums), Presenting… begins auspiciously with “Machines.” A Mort Shuman composition originally cut by Manfred Mann in 1966, the track rides a ludicrously chunky, mechanical rhythm while the singer belts a cautionary tale about said machines transforming from things that serve humans to becoming our enslavers. The grim message almost gets lost in the robotically bouncy joy the music induces.

A jarring transition occurs with “This Is It,” an easy-going, jazzy charmer that carries the air of a sly Mose Allison tune. The melody is sophisticated yet attention-grabbing, immediately burrowing itself into your memory bank and wiggling adorably there forever more. More catchiness ensues on “This May Be Goodbye,” a psych-pop tune toggling between endearing and annoying, thanks to John Emelin’s nasal, forceful vocals, and “That’s Another Story,” which feels at once old-timey and as hip as Pentangle-esque folkadelia, thanks to its wonderful see-sawing melody.

LATHP could go hard, too. “Sex And Violence” is a groovy, heavy jam featuring the title chanted and sung menacingly. Rusty Ford’s bass line is sick and the guitar solo anticipates Butthole Surfers freak Paul Leary. The tough yet baroque garage rock of “You Won’t Be Lonely” evokes Detroit’s SRC. “It Comes On Anyhow” is the most psychedelic and disjointed moment on the record, full of “OM”s, warped harpsichord motifs, Paul Conly’s synth drones, Tom Flye’s huge beats, and mutterings of “It doesn’t matter.” Imagine a more concise “Revolution 9.”

For Moog-lovers, Conly shines on “Milkweed Love,” an ominous ballad in the vein of Mort Garson and Jean-Jacques Perrey, and “Paul, In Love,” a beautiful reverie à la Garson’s Plantasia. Plus, nearly every song here is capped by little Moog filigrees.

A cloying wackiness occasionally mars Presenting… “Kids Are Little People”’s goofy children’s-television rock and “Woody Woodpecker” (yes, the cartoon theme) especially annoy. But the loony-bin-bound pop of “Ha (Ho)” at least has the decency to end with an enticing electronic coda that foreshadows Tonto’s Expanding Head Band. Thankfully, most of this LP hits the sweet spot between sublime and silly. These songs may carry an indelible late-’60s timestamp, but that only adds to their charm when heard in 2020. -Buckley Mayfield