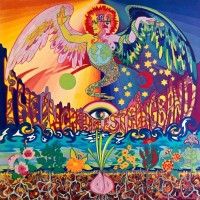

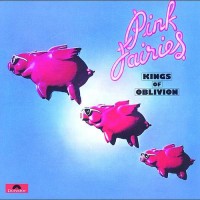

If you are curious about inspired Motorhead’s unique sound, and have already explored MC5, The Stooges, Hawkwind and The Groundhogs, then go no further than this album. Larry Wallis and Duncan Sanderson later appeared on Motorhead recordings and the song “City Kids”, debuting here, is also featured on Motorhead’s 1979 LP On Parole. “City Kids” here is more stark than Lemmy’s amphetamine-enriched version, but no less powerful. ‘I wish I was a Girl” is a track worthy of the Groundhogs “Split” album in its inventiveness – but the raw power is undiminished. Sure it lacks a little something due to recording techniques in those days – a clear sense of perspective is needed, as this is music of its time and yet way ahead of it. “When’s the Fun Begin” is not one to listen to if you’re verging on a depression, but provides a nice contrast to the driving “Chromium Plating” and “Raceway.” Something about these tracks actually seems to contain the acrid smell and excitement of motor racing in a far less clinical way than say, Fleetwood Mac’s “The Chain.” “Chambermaid” is quirky and may require several listens to pick up on the humour, and “Street Urchin” is the track that leaves you wanting more.

Kings of Oblivion is one of the best-kept secrets of hard rock – and an important part of its history. If you like your rock and roll “real,” it doesn’t get much more real than this. Just don’t go expecting Judas Priest, AC/DC or Black Sabbath; This is high-energy rock that truly belongs on the streets, and a landmark album in its genre. Truly a classic. —Fuuhq