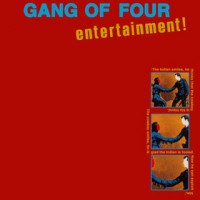

It’s hard to recognize the importance of music like this in an era when Marketing is considered a legitimate university degree. So we have to have a little historical imagination to look back to a time when political possibilities weren’t limited to corporate tyranny, mindless technocrats, and buzzwords worthy of Nazism. Yes, kids, politics used to be funky, and music even sometimes had brains.

If you don’t agree with their politics and you like their music, you just don’t know it yet that you agree with their politics. You’ll either come around or you’ll stop listening to Entertainment! Further to that point: you don’t have to be a Marxist to acknowledge the falseness of commercial culture and the “globalized” post-modern neurotic subject. So you don’t have to worry about being called a Red. Which if you’re worried about it, you aren’t ever gonna get the message, anyway.

Though I suppose the lazy-fair types are always gonna think that economics is a science when it’s under critique and a board game when it’s not, and that art’s a form of entertainment, subject to market competition just like antidepressants and military contracts. Which is why Marketing is such a goshdarnit important substitute for Marx in today’s active lifestyles. —Will