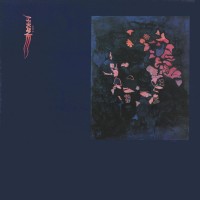

All it takes is about 10 seconds of a Woo song to understand that you’re in the presence of utterly distinctive artists who appear to operate in cloistered, idyllic settings, far from the usual circumstances of music-making. British brothers Clive and Mark Ives use electronics and percussion and guitars, clarinet, and bass, respectively, to create music that eludes easy categorization. They touch on many styles, including chamber jazz, ambient, dub, prog-folk, exotica, twisted yacht rock, Young Marble Giants-like post-punk, and winsome miniatures not a million miles from Eno’s instrumentals on Another Green World.

Listening to their releases, you sense that the Iveses are totally unconcerned about music-biz trapping; neither fame nor fortune seems to enter their minds. They simply want to lay down these genuinely idiosyncratic tunes that work best in your headphones/earbuds while you’re alone in nature. That’s an all-too-rare phenomenon.

Recorded from 1975 to 1982 in London, Awaawaa only recently gained wider recognition, thanks to a 2016 reissue by the Palto Flats label. Its 16 instrumentals rarely puncture their way to the forefront of your consciousness. Rather, they enter earshot with low-key charm, do their thing for a few minutes, then unceremoniously bow out. “Green Blob” is the closest Woo get to “rocking out,” coming across like CAN circa Ege Bamyasi (sans vox) burrowing deeply into inner space, with Mark Ives’ guitar recalling Michael Karoli’s yearning, clarion tone. Similarly, “The Goodies” sounds like the Residents interpreting CAN, casting the krautrock legends’ irrepressible groove science in a more insular context.

The pieces on Awaawaa exude an unobtrusive beauty, a congenial mellowness; the cumulative effect is a subtle, holistic well-being. It’s a sprig of joy that will keep you enraptured and hearing new delights with each successive listen. -Buckley Mayfield