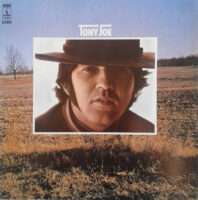

The late Tony Joe White should’ve been at least 75% as popular as Elvis Presley. He had the deep, sexy voice, the knack for telling vivid stories in songs set in his Louisiana swampland youth, the tight guitar playing, a sly sense of humor, and the rugged good looks. TJW was the whole package, and he was more versatile than Elvis (who charted with White’s own biggest hit, “Polk Salad Annie”). So while Tony had some commercial success (the aforementioned hit in the last sentence and “Rainy Night In Georgia”) and wrote a couple more blockbusters for Tina Turner ca. 1989, he didn’t come close to the fame and fortune of his fellow Southern stud. Life ain’t fair, etc.

TJW’s first five albums from 1969-1972 are all great and representative of his prodigious sangin’ [sic], songwriting, and guitar-pickin’ skills. I could’ve written about any of them, but I chose his third LP, Tony Joe, because I dig the poncho Tony’s wearing on the back cover and the horse he’s riding looks cool. I also picked Tony Joe because it starts with one of White’s toughest tracks, “Stud Spider,” which Light In The Attic Records placed on the first comp of its essential Country Funk series. In conjunction with Muscle Shoals hotshots Norbert Putnam (bass), David Briggs (organ), and other session-musician ringers hanging around Nashville studios at the time, White weaves a lustful tale of love via the metaphor of spider behavior while he and the boys erect a slow-burning funk edifice to accentuate the lyrics’ drama. Kanye West and Common have sampled Jerry Corrigan’s drums from this one, and it’s surprising more hip-hop producers haven’t.

Further excursions in grooviness occur with “Save Your Sugar For Me,” a paragon of country-funk accessibility, with White’s trademark libidinousness leading the way and female backing vocalists (uncredited, unfortunately) adding that titular sweetness. With natural gusto and grunting lasciviousness, Tony embodies the Southern-fried braggadocio of Otis Redding’s “Hard To Handle.” Clearly, TJW was born to perform this soulful crotch-scorcher. “What Does It Take (To Win Your Love)” (previously done by Jr. Walker & The All Stars) reveals White’s tender side with mellifluous harmonica playing and a confidential singing tone.

Another highlight occurs on “Conjure Woman,” an ominous pounder about a swamp-dwelling witch whom the narrator feared would put a spell on him. The album’s low point is Donnie Fritts/Spooner Oldham’s “My Friend,” a string-heavy ballad that unfortunately tumbles into the maudlin column. White’s better when he straps on the acoustic for some minimalist blues, as he does with “Stockholm Blues” and “Widow Wimberly.” Speaking of blues, White really rises to the occasion with his take on John Lee Hooker’s lean, menacing 1962 original of “Boom Boom.” He lays on the hambone-tough-guy persona thickly while playing mean harmonica and subtly savage electric guitar over the top of the classic’s pitiless lope. This version’s nearly eight minutes long, and it’s all gripping. Ain’t no way Elvis could do it better… -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.