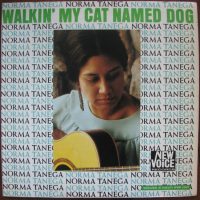

Though she had a single that reached #22 on the charts in 1966 and wrote songs for British pop-soul diva Dusty Springfield (with whom she also had a long-term romantic relationship), Norma Tanega has remained an obscure cult figure. Call me an optimist, but I think that situation might be remedied by Real Gone Music’s recent green-vinyl reissue of Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog, a delightfully quirky folk-rock record that quickly charms its way into your heart—especially that chart-dwelling title track alluded to earlier. I mean, RGM only produced 1,000 copies, but maybe this review will tip the scales in Tanega’s favor. (HAHAHAHA.)

All kidding aside, you gotta love the moxie of opening your debut album with a song title “You’re Dead.” Tanega grabs you from the get-go with a matter-of-fact voice that’s somewhat flat yet alluring, like Bobbie Gentry (or indeed Springfield), with a lower timbre and less breathy flamboyancy… or like Buffy Sainte-Marie without the stentorian vibrato. Tanega’s music is urgent, stripped-down folk-rock that gives Bob Dylan and Phil Ochs’ songcraft a run for its trenchancy. “Treat Me Right” is upbeat folk with gospel-vocal call-and-response uplift. “Waves” and “Jubilation” form a diptych of feel-good, intimate anthems that celebrate coupledom, in waltz time.

The dramatic orchestral pop of “Don’t Touch” features a chorus paraphrasing that of Petula Clark’s “Downtown.” It should’ve been a hit! What did become a hit, “Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog,” is simply one of the greatest songs of the ’60s, a lolloping melody that makes you want to tear off all of your clothes, wad ’em up, and throw ’em in the air. Mutedly euphoric, the song sounds like Martha & The Vandellas gone folk, and it reflects Tanega’s genius for surprising song structures and idiosyncratic harmonica tones. “A Street That Rhymes At Six A.M.” offers another Motown simulacrum, but in off-kilter folk mode. So damn fresh.

For variation, there’s “What Are We Craving?” (a stomping, martial tune with Nico-like vocals), “No Stranger Am I,” (an Astrud Gilberto-esque saudade folk tune in an odd time signature), and “Hey Girl” (a cover of the 1870s Appalachian folk standard “In The Pines,” which was made famous by Lead Belly… and then more famous by Nirvana and Mark Lanegan). Oddly, the album closes with its most conventional track, “I’m The Sky,” whose jaunty poppiness recalls the 5th Dimension.

Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog is one of the most welcome reissues of the year. The fact that the latest edition of it already has sold out bodes well for its rehabilitation. Now get to repressin’, Real Gone Music. -Buckley Mayfield