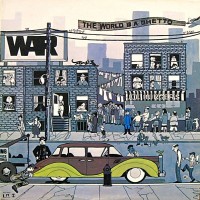

I’m not in the habit of reviewing records that have dwelled on the charts (it went to #1 and was Billboard magazine’s album of the year, selling more copies than anything else in 1973), but War’s The World Is A Ghetto ain’t your typical platinum LP. Sure, smash single “The Cisco Kid” greatly helped its ascension, but when you get beyond that feel-good, heavy-lidded funk shuffle, things get dark, psychedelic, and real as shit.

On this, their fifth full-length, War were really hitting their stride. The large LA ensemble had proved they excelled at funk, rock, Latin, R&B, calypso, and fusions thereof—with and without ex-Animals vocalist Eric Burdon. Their music was geared for outdoor parties and radiated a bonhomie that you sensed aspired to unite racial and social groups—even on ostensibly ominous cuts like surprise radio staple “Slippin’ Into Darkness.”

Still, some critics have lamented the extended length of songs like “City, Country, City,” “Four Cornered Room,” and the title track, but fug these short-attention-spanned busters. If concise songs are more your speed, though, you’ll love the aforementioned “Cisco Kid” and “Where Was You At.” The latter’s a brisk, clipped funk number with gospel call-and-response vocals, with its irresistible groove toggling between tough and breezy. The sub-4-minute “Beetles In The Bog” is one of those let’s-end-the-album-on-a-rousing-note songs, powered by massed “la la la”s, a nimble, strutting bass line, and a martial rhythm.

But the real nitty-gritty of The World Is A Ghetto occurs on its longest tracks. “City, Country, City” is a 13-minute instrumental that vacillates between passages resembling Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” and bustling, urban jazz-funk that nearly beats Kool & The Gang at their own game. War seriously stretch out and build up a humid head of steam here. A midnight-blue ballad, “The World Is A Ghetto” is suffused with a sublime malaise over its 10-minute duration, but it possesses enough gumption to keep its chin up in the struggle to survive, despite the pervasive gloom of the song’s sentiment.

With “Four Cornered Room,” Ghetto hits a shocking peak. It starts with one of the starkest, most menacing blues-rock riffs to which you’ve ever trembled (oddly, you can hear its influence in the later work of Seattle drone-metal deities Earth). The massed “ooh”s and “zoom zoom zoom”s add layers of chillingness to the song, while the phased and panned guitar and percussion disperse things into a psychedelic zone of extreme zonkedness. It sounds like War wrote and recorded this tune after smoking some extremely strong ganja, playing as if in a paranoid daze. “Four Cornered Room” puts most stoner rock to shame. Low-key, it’s a career highlight in a catalog loaded with diverse zeniths. -Buckley Mayfield