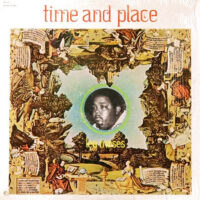

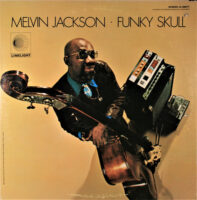

Chicago-based Melvin Jackson—who served as the bassist for popular soul-jazz-funk saxophonist Eddie Harris and played on John Klemmer’s 1967 album for Cadet, Involvement—released but one solo LP, Funky Skull, but oh, what a cool platter it is.

Jackson had access to several amazing musicians, who helped to elevate Funky Skull to cult-classic status. The roster includes guitarists and Cadet Records session studs Pete Cosey and Phil Upchurch, trumpeters Lester Bowie and Leo Smith, saxophonists Roscoe Mitchell and Bobby Pittman, and drummer Billy Hart. Despite some of these musicians having reps as serious jazz cats, they contribute to a record to which you can get down. “Funky Skull (Parts 1 & 2)” delivers churning, ebullient funk marked by Jackson’s trademark quacking bass and party-igniting horn charts by Pittman, James Tatu, Tobie Wynn, Tom Hall, and Donald Towns. Similarly, “Cold Duck Time – Parts 1 & 2” (written by Eddie Harris) offers more torqued, uproarious funk with slapstick “bee-ow bee-ow bee-ow”s from Jackson’s hooked-on-helium bass. (The unique timbres he achieves are instant smile-inducers.) “Cold Duck Time” is the cut you play when you want to launch the party to the next debauched level.

“Funky Doo”—a cowrite with the album’s producer, Robin McBride—boasts vocals by the Sound Of Feeling, but it’s eccentric feel-good funk in a slightly less exuberant mode than “Funky Skull” and “Cold Duck Time.” Another Harris tune, “Bold And Black,” melds Rotary Connection-like soul sublimity with groove-centric jazz, as singer Maurice Miller adds gospelized power. It’s inspirational, but kind of low-key with it. I like the cut of its jib.

“Dance Of The Dervish” is an excursion into abstraction, an opportunity for Jackson to flex exploratory muscles on his array of effects and to thereby disorient those who came to simply blow off steam. It’s a psychedelic curve ball, replete with Echoplexed, robust laughter. Another outlier is “Say What,” low-slung spy jazz on which Jackson’s bass sounds more like a distraught, weeping violin. “Silver Cycles” (which Jackson cowrote with Harris) is a cover of one of the saxophonist’s most transcendent and trippy compositions. No, it doesn’t top the original, but it’s a bold attempt.

Heads up: the Verve By Request label is reissuing Funky Skull on December 8—nice timing for that Kwanzaa/Hanukkah/Xmas gift. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.