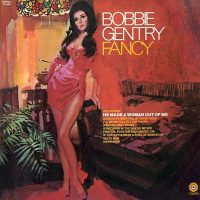

Even though she had a massive hit in 1967 with “Ode To Billie Joe” and released a grip of great LPs from in the late ’60s and early ’70s, Bobbie Gentry is not quite the household name she should be. Much like her English counterpart Dusty Springfield, the Mississippi-born Gentry is a soulful, nuanced vocalist who could work wonders with country, funk, rock, and pop material. Aside from singing in her supple, sensuous contralto, Gentry also wrote, produced, and even did the artwork for some of her album covers (including Fancy). She exerted a lot of control over her career for a woman in a male-dominated industry that wasn’t as progressive as it wanted to think it was.

Although she had sporadic chart success in the US and UK, and even hosted her own variety show on BBC TV, Gentry faded from the music biz and the public eye in the early ’80s. But her profile’s received a boost in recent years after being name-checked by young country-music stars like Kacey Musgraves and Nikki Lane, as well as the recent release of the 8-CD box set The Girl From Chickasaw County: The Complete Capitol Masters, should further raise Gentry’s profile… [ahem] as well as this review.

The title track establishes Fancy‘s main mode: slick, orchestral country-funk executed by excellent session musicians from the Fame Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama and in Columbia Studios in Nashville. The lone Gentry original, “Fancy” finds the singer recounting the rags-to-riches story of an 18-year-old woman whose mother nudges her into a life of prostitution to lift the family out of poverty. It’s so good, one wonders why Capitol larded the rest of the LP with other people’s compositions. On the two Bacharach-David tunes—“I’ll Never Fall In Love Again” and “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ On My Head”—Gentry’s Southern-belle gravitas doesn’t thrive in the famous songwriting team’s spick-and-span suburban pop, no matter how well-crafted it is. She sounds a bit uncomfortable and out of her soulful element here. Similarly, the cheerful, waltz-time pop of Rudy Clark’s “If You Gotta Make A Fool Of Somebody” does not play to her strengths.

Thankfully, Gentry shines on the rest of the album. While Laura Nyro’s “Wedding Bell Blues” may not be the most copacetic vehicle for Gentry, the melody is so sublime that she can’t help making a gorgeous swoon of yearning heartache out of it. Leon Russell’s “Delta Man” is a song into which Gentry can really sink her incisors. She switches the original song’s genders and lays into Russell’s rousing chorus with less brio than Joe Cocker did, but Bobbie out-finesses the English geezer by far.

“He Made A Woman Out Of Me” (written by Fred Burch and Don Hill and earlier covered by Bettye LaVette) is Southern country-funk that’s as lubricious as Tony Joe White at his most seductive. It’s a momentous coming-of-age tale… so to speak. The album’s highlight is Harry Nilsson’s “Rainmaker”; it’s the funkiest, most sweeping track here, augmented by banjo and violin—not exactly staples of the funk genre, but Gentry, producer Rick Hall and his Muscle Shoals crew, and strings arranger Jimmie Haskell make it work to the max. This is my go-to track on Fancy for DJ sets—so it has that going for it, too.

While I’d prefer to hear Gentry perform her own songs, on Fancy she inhabits other composers’ with sly charisma, imbuing them with a strong wiliness that was rare for its time among female entertainers. -Buckley Mayfield