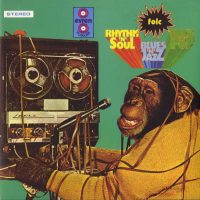

After much listening and thought, I have to conclude that Mustafa Özkewnt VE Orkestrasi’s Gençlik İle Elele is a perfect record, a paragon of Turkish funk. Its 10 instrumental tracks average a little over three minutes in length, but they’re so rhythmically tight and tonally and texturally fascinating, that they feel like teases. Every element here—swarming, swirling John Medeski-esque soul-jazz organ, trebly, frilly-tendrilled guitar, in-the-pocket drums, furious bongo- and conga-slapping and other hand-percussion accents—is laser-focused to get your head bobbing, your hips swiveling, and your loins flooded with do-it fluid. So, yeah… a perfect record.

This LP, as you may surmise, contains loads of chunky funk that’s ripe for sampling by enterprising hip-hop producers; it’s a veritable breakbeat orgy. But according to online authority whosampled.com, only four Mustafa Özkent tracks have been sampled. That seems low for an album of such bumpin’ bounty. Not surprisingly, Madlib’s brother Oh No used two songs from Gençlik in his own work; surprisingly, Madlib himself hasn’t plundered it… not yet, anyway.

The concision and airtight beat science displayed by Mustafa Özkent and company recall the Meters’ disciplined approach to funk. Of course, being Turkish, Mustaf Özkent sound a tad more non-Western in their melodies and timbres. (According to Andy Votel’s liner notes in the 2006 B-Music reissue, Özkent modified his guitars with extra frets to make it sound more like a saz or a lute.) And that makes a big difference with regard to the stunning impact this album makes on the Western listener. All that being said, the phenomenal bass solo on “Dolana Dolana” would make Larry Graham give two thwapping thumbs up.

Reissued again by Portland label Jackpot in 2016, Gençlik İle Elele—which means Hand In Hand With Youth—should never fall out of print, nor stray far from your DJ bag, if indeed you DJ. Hell, this record just may inspire to start working the 1s and 2s yourself… -Buckley Mayfield