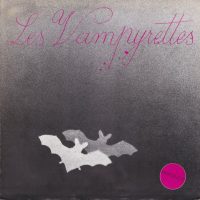

The two tracks that comprise this ultra-obscure EP by Les Vampyrettes (revered krautrock studio wizard Conny Plank and the late, great Holger Czukay of CAN) represent some of the most sinister music ever laid to tape. For decades, however, Les Vampyrettes was strictly the province of the world’s most elite collectors. Thankfully, in 2013 the great Grönland label reissued the record. (You can also find these cuts on Czukay’s just-released 5xLP Cinema box set.)

Pulling off sinister music is more difficult than it may seem, as it’s easy to topple into hokeyness or ham-fisted Hollywood tropes when venturing into hellish sonic miasmas. As you would expect from two masters of sound sorcery such as Plank and Czukay, Les Vampyrettes avoid those pitfalls. Holger proposed to Conny a series of singles with the theme of “horror with comfort,” and Les Vampyrettes resulted. They infuse the music here with a gravity and oppressiveness that are truly remarkable.

“Biomutanten” is a four-minute collage of seemingly random noises, but the way Les Vampyrettes arrange and produce them is chilling. Ominous pulsations and panicky ticking sounds, doom-laden twangs, alarm bells, emergency warning signals, Doppler-effected wails, myriad noises hinting at things going awry, a pitched-down-to-hell (literally, it seems) male voice speaking in German—all of these elements induce a serious dread and a feeling of a tenuous grasp of sanity gradually slipping. Do not listen on hallucinogens… unless you really want to lose your marbles.

“Menetekel” is a slightly shorter minimalist creepscape haunted by insectoid chirps, warped warbles, dripping and splashing water, and those guttural, lower-than-low/slower-than-slow German guy intonations. It’s not quite the mindfuck that “Biomutanten” is, but it’s still the antithesis of party music.

As fantastic and phantasmagorical asConny Plank and Holger Czukay’s discographies are, they may have conjured their most outlandish vibe with this one-off project. At certain times of the night, Les Vampyrettes might be regarded as both geniuses’ peak work. -Buckley Mayfield