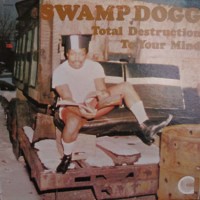

(Little) Jerry Williams is one of those stalwart R&B/soul songwriters/performers who had some modest success in the ’50s and ’60s with solid but fairly conventional tunes. And then in the late ’60s our hero ingested some LSD, the ’70s commenced, and Williams became Swamp Dogg and took his music into much more eccentric and interesting territory. His debut full-length under that alias announced the arrival of a soul maverick. Total Destruction To Your Mind is a righteous cult classic that’s aged shockingly well.

The record peaks early with the dynamite 1-2 spiked punch of the title track and “Synthetic World.” The former’s an unstoppable burbling funk party jam fueled by liquid wah-wah guitar, bold horn flourishes, and Williams psychedelic-soul vocals redolent of Otis Redding’s Southern-fried throatiness. The latter’s laid-back funk with a country-folk lilt in the swampy (yes!) vein of Tony Joe White.

The two Joe South covers are fab, because Joe South was unfuckwithable in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Williams tackles “Redneck,” a sarcastic dig at bigoted white guys, and he really sinks his fangs into South’s good-ol’-boy chug with rollicking piano and horns that want to get you drunk. “These Are Not My People” is funky folk boasting a vibrant, catchy-as-hell melody; this song should’ve been a hit for both the composer and for Mr. Dogg.

A couple of other highlights: “If I Die Tomorrow (I’ve Lived Tonight)” brings more Redding-style testifying, just oozing real-shit emotion while “Sal-A-Faster” offers lean, menacing funk akin to Whitfield-Strong’s “I Heard It Through The Grapevine” (think the Temptations’ version). And “I Was Born Blue” proves that Williams could render a heart-shattering ballad with one of the greatest key changes in soul music. It’s pathos overload, not unlike that in the Bee Gees’ “I Started A Joke.” It gave my throat lump goose bumps.

Alive Records reissued Total Destruction To Your Mind in 2013, doing the world a humanitarian service that you’d do well to not let go to waste. -Buckley Mayfield