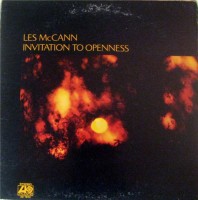

You probably know keyboardist Les McCann for his uproarious hit with Eddie Harris, “Compared To What,” but with Invitation To Openness, he occupies a much more chill zone, as exemplified by the 26-minute lead-off track, “The Lovers.” The opening keyboard movement foreshadows a blissful peace, not unlike Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way, with Corky Hale’s harp trills adding more timbral tranquility to proceedings. A few minutes in, drums and percussion slide into earshot and a laid-back groove akin to Julian Priester’s sublime “Love, Love” commences, aided by Bill Salter’s stealthy bass. Five minutes in, Yusef Lateef takes the piece to a higher level with snake-charming oboe melismas. Five minutes later, Cornell Dupree and David Spinozza (who’s worked with Paul McCartney and John Lennon) peel off some wah-wah-tinged blaxploitation riffs that seriously enliven the song, inspiring Bernard Purdie (or it Alphonse Mouzon?) to funk up the rhythm to the max.

“The Lovers” waxes and wanes (but mostly waxes) over its long duration, sounding remarkably composed for an improv jam featuring more than a dozen players. It’s one of the most magical spontaneous-epic recordings in the post-Coltrane world, a cool outpouring of loving spirit by musicians working at the loftiest level of groupmind telepathy. Love, love it.

By contrast, side two can’t help seeming somewhat less momentous. Nevertheless, the two long cuts on it are worth playing in your next hip lounge DJ set. The 13-minute “Beaux J. Poo Boo” is subtle soul-jazz that, while it’s playing, makes you feel about nine times cooler than you actually are. Its gentle propulsion and Lateef’s fluid, mellow flute arabesques lull you into a state of contentment until close to the end, when nearly all hell breaks loose. But these cats are too cool to ever really go nuclear with the freakouts.

On the 12-minute “Poo Pye McGoochie (And His Friends),” we hear another pensive beginning before the band heats up with advanced, velvety groove science. McCann’s crispy, spacey Moog motif rears its head periodically to break up the intricate, cerebral passages. Once you hear that Moog brashly flexing, you’ll want to call it up in your mental jukebox every time you need a jolt of adrenaline. Bonus: a badass drum solo near the end by Mouzon (I think). As with the other two pieces, it sounds like all the players amassed in the studio under producer Joel Dorn were simply enjoying the hell out of themselves and reveling in the loose sense of adventurousness McCann had instructed them to strive for.

Invitation To Openness is one of those rare classics you can still find in used-vinyl bins for $1-$5. Snap it up. -Buckley Mayfield