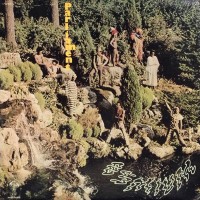

Osmium captures Parliament (aka Funkadelic) at a time before their trademark stylistic traits had firmly solidified. Consequently, it’s a wildly diverse record, full of songs both expected (if you’re familiar with the P-Funk catalog) and very surprising—like, “check the record to make sure this is still the band from Detroit led by George Clinton” surprising. Yes, Osmium is at core a soul album, but it’s a helluva lot more, too. Because any George Clinton production—especially from the ’60s and ’70s—can never be typical.

Osmium—alternately titled Rhenium and First Thangs in subsequent releases; a 2016 reissue of it is floating around, too—begins with a prime slice of horndog funk, “I Call My Baby Pussycat,” with Eddie Hazel and Tawl Ross’ guitars and Billy Bass Nelson’s bass really setting fire under asses. Things grind to a solemn halt with “Put Love In Your Life,” a soul-gospel-tinged ballad sung with baritone gravity by Ray Davis… but then it unexpectedly shifts into a florid psych-pop anthem. Wow, my ears just got whiplash. If that weren’t strange enough, the Ruth Copeland-penned “Little Ole Country Boy” swerves into mock-country territory, replete with jaw harp, tabletop guitar embellishments, and Fuzzy Haskins’ Southern-honky vocal affectations; think the Rolling Stones, but with tongues more firmly jammed in cheek. More ear whiplash. Ouch! (Yes, De La Soul producer Prince Paul sampled the yodeling part for “Potholes In My Lawn.”)

“Moonshine Leather” peddles the sort of sublimely sluggish bluesy funk that occupied some of Funkadelic’s earliest releases, while “Oh Lord, Why Lord/Prayer” is a baroque-classical/gospel hybrid, sung with utmost passion and soul by Calvin Simon and Copeland. It’s definitely the frilliest and most churchy P-Funk track I’ve heard. As an agnostic, it sort of gives me hives, but there’s no denying the sincerity and skill behind the song.

Side two begins with “My Automobile,” yet more Stonesy faux country, but with sitar (?!) accompaniment, quickly followed by the revved-up, libidinous “Nothing Before Me But Thang,” which is the wildest, most Funkadelicized cut on Osmium. The struttin’, ruttin’ “Funky Woman” is indeed funky and ready to make any party you’re attending lit, as the kids say. The hippie-fied gospel rock of “Livin’ The Life” sounds like something off of Godspell or Hair, but it’s not bad at all.

Parliament saved the best for last with “The Silent Boatman.” Another Ruth Copeland composition (she also co-produced the LP, by the way), “The Silent Boatman” is one of the most beautiful and moving songs in all creation. A slowly building, majestic ballad aswirl in Bernie Worrell’s organ and glockenspiel, it’s a poignant tale lamenting inequality and strife on Earth and redemption in the afterlife. When the bagpipes come in, you feel as if you’re being swept up in a highly improbable dream in which Parliament become the most persuasive religious sect ever to enter a studio. Going way against type, “The Silent Boatman” might be the closest Clinton & company ever got to godliness. Ruth Copeland was their secret weapon, although she never again recorded another proper album with the group. But what a legacy she left. -Buckley Mayfield