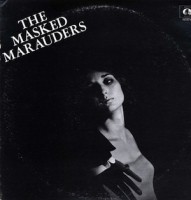

An album that caused much curiosity as well as controversy when it was released late in 1969. The entire concept and mystique of The Masked Marauders (many would call it a hoax) was the brainchild of a then-staff writer at Rolling Stone magazine. From the beginning, the writer only intended it to be a joke, and pushed it to the extreme by printing a phony article about the band in Rolling Stone, as well as touting the upcoming release of the album. The joke obviously worked from the writer’s point of view, but apparently, the record-buying public didn’t get it.

The Masked Marauders were rumored to consist of Paul McCartney, George Harrison, John Lennon, Mick Jagger and Bob Dylan, all of whom supposedly performed on the record anonymously and without photos to preserve the “secrecy” (hence the group’s name). This caused the rumor mill to churn, and public anticipation of the album was so high that people lined up in droves at record shops to buy it on the day it was released. But as it turned out, the Masked Marauders were indeed not the “supergroup” everyone thought them to be, but actually a group of struggling studio musicians calling themselves “The Cleanliness and Godliness Skiffle Band”. Confused? Don’t feel bad, everyone else was, too!

The album’s hilarious liner notes alone showed that it totally reeked of farce, with the aforementioned Rolling Stone writer composing them under the pseudonym “T.M. Christian”. For those of you who don’t understand what that means, “T.M. Christian” is a play on words for a Peter Sellers movie from that same period called “The Magic Christian”, which also featured Ringo Starr. That probably explains why Ringo didn’t have time to appear on the Masked Marauders album (tongue firmly in cheek there!) The best bits of the liner notes are, and I quote: “leading experts now estimate that the music industry is 90% hype and 10% bullshit”; and “in a world of sham, the Masked Marauders, bless their hearts, are the genuine article” (are you getting the picture now?)

Now if all of THAT wasn’t enough to send you into hysterics, here’s the lowdown on the music: many of the songs on the album are every bit as tongue-in-cheek and performed the same way. For example, the lead track “I Can’t Get No Nookie” comes complete with a nearly dead-on vocal impersonation of Mick Jagger, and the classic “Duke Of Earl” is given another hilariously accurate impersonation, this time of Bob Dylan. Also included is a 10 minute-plus version of Donovan’s “Season Of The Witch”. This could qualify as the only “serious” track on the album, and it’s actually performed quite well; one of the best versions I’ve heard next to the one on the album “Super Session” by Mike Bloomfield, Stephen Stills & Al Kooper (yes, they were a REAL supergroup!)

If you got the “joke”, then get the album; for what it is, you’ll enjoy it! —Chuck