Discovering library music is a fascinating thing. This is music that was initially created for commercial purposes (created to be sold or licensed to film, television or radio). Library production music can be the most liberating, genre-bending musical experience, due to its lack of constraints on creativity. It varies from straight orchestral fare, bossa nova pop, quirky electro, disco, demented and moody electro-acoustics, folk, and everything else in between.

There were numerous labels of all shapes and sizes, mostly from France, Italy, Germany and the UK (L’illustration Musicale, de Wolfe, Telemusic, KPM, Selected Sound, Musique Pour l’Image, and Bruton being among some of the larger, more reknown labels), some with wide distribution, and others relegated to obscure status almost immediately. Composers would knock out several albums a month, often for different labels, and even more common, under a different name – leading to very difficult research, and a very tricky time for anyone trying to figure out any sort of discography trajectory. Some examples of aliases include the ever prolific Piero Umiliani, who also traded under Zalla, Moggi, Herbana, The Braen’s Machine (with Alessandro Alessandroni), and a few others. Nino Nardini was another big composer, getting his start in the 40’s as a big band jazz leader, soon becoming one of the towering figures in all of library music, often under his Georges Teperino guise. His friend and recurring musical partner Roger Roger typically issued zany electronics under the name Cecil Leuter. This story is typical among the legions of composers.

I feel the high point of library music vitality was from roughly 1968-1982, though the amount of decent 80’s libraries is scarce. Further into the 80’s the music got increasingly tacky, especially on the British labels Bruton, de Wolfe and KPM, mixing rock elements with fusion and disco, resulting in many failed ideas that neverless ended up gracing many television programs and radio themes.

These are pretty broad statements meant to clue some folks in to library music as a whole, though on the fringes there were numerous small labels who only issued a few albums, and even still, some labels are only noteworthy through rumor, having become so scarce as to not being tracked down at all. Many of these labels produced some very challenging and often avant garde music, some venturing more into the modern interpretive dance music, and less a commercial venture. I’m sure there are so many thousands of stories hidden within those recording studios, television and radio stations, etc… with hundreds of faceless, seemingly selfless composers pushing out the goods to little or no fanfare. Some of these composers were relatively famous through other means and did libraries for a little extra cash (many tracks did in fact became famous themes for TV, radio and film). For some of these composers, it was their sole creative and financial venture, but it’s safe to say that now for many younger people who’ve discovered them anew, they are like rock stars.

Much of this music is a goldmine for sample hungry beatheads looking for “breakz.” I tend to approach it differently. Sure, I love a good solid groover, but I also look for something more cerebral, conceptual, or just plain different, to go deeper than just funky instrumental music.

Picking just several favorites was a difficult task. The ten titles below were chosen to showcase a variety of composers, labels and styles. A quick Google search of a composer or favorite title will quickly put you on your own path of discovery.

1. Sven Libaek Solar Flares (Peer/UK, 1974). One of my favorites! A very solid collection of groovy orchestral pop, but with that Libek twist: lots of dreamy vibes, clever, hooky arrangements, subtle wah-guitar, sneaky Moog, strong brass work, etc… Many fantastic tunes here, with a slight futuristic bent, but more in line with hazy summer days circa 1975.

1. Sven Libaek Solar Flares (Peer/UK, 1974). One of my favorites! A very solid collection of groovy orchestral pop, but with that Libek twist: lots of dreamy vibes, clever, hooky arrangements, subtle wah-guitar, sneaky Moog, strong brass work, etc… Many fantastic tunes here, with a slight futuristic bent, but more in line with hazy summer days circa 1975.

2. Oronzo de Filippi Meccanizzazione (Leo/Italy, 1969). A stunning library album featuring a strange mix of Morricone harpsichord phrasings, Jobim esque bossanova lounge, and some shifty Dave Brubeck tempos, with little bits of weird sounds thrown in. All in all it’s very sunny, hypnotic stuff. Deserves to be recognized as a solid latin jazz album. There’s a strong resemblance to Dots… era Stereolab in parts, regarding the jazzy latin rhythms and instrumentation.

2. Oronzo de Filippi Meccanizzazione (Leo/Italy, 1969). A stunning library album featuring a strange mix of Morricone harpsichord phrasings, Jobim esque bossanova lounge, and some shifty Dave Brubeck tempos, with little bits of weird sounds thrown in. All in all it’s very sunny, hypnotic stuff. Deserves to be recognized as a solid latin jazz album. There’s a strong resemblance to Dots… era Stereolab in parts, regarding the jazzy latin rhythms and instrumentation.

3. Serge Bulot Les légendes de Brocéliande (Sonimage/France, 1981). Moody and atmospheric, this is a very strong album – veering from ambient synth and folksy acoustic guitars to subtle violin arrangements; all set against a dreamy, swirling early 80’s post-punk haze that’s actually quite effective, recalling at once a sort of Factory records Durutti Column/Virginia Ashley type collaboration with some very slight ambient prog tendencies from the late 70’s. Bulot is a noted multi-instrumentalist with a vast, impressive collection of worldly instruments. From the looks of his myspace page he’s currently quite active composing and performing.

3. Serge Bulot Les légendes de Brocéliande (Sonimage/France, 1981). Moody and atmospheric, this is a very strong album – veering from ambient synth and folksy acoustic guitars to subtle violin arrangements; all set against a dreamy, swirling early 80’s post-punk haze that’s actually quite effective, recalling at once a sort of Factory records Durutti Column/Virginia Ashley type collaboration with some very slight ambient prog tendencies from the late 70’s. Bulot is a noted multi-instrumentalist with a vast, impressive collection of worldly instruments. From the looks of his myspace page he’s currently quite active composing and performing.

4. Francis Monkman Tempus Fugit (Bruton/UK, 1978). Phonkay space age fuzak! Here the keyboard wiz tears through stellar fantasy lifestyle music, with the terse focus of a falcon and the cheese merchant chops of Rick Wakeman’s little brother (?). Of course, this was on the British late 70’s standard jazz disco funk label Bruton. Here you’ll find plenty of Rhodes massaging, synth-swell galore, and hard clavinet stomping mood pieces that do little to deter your image of spacemen in tight red leather pants, headbands and elbow length white gloves. Run (don’t walk) away slowly.

4. Francis Monkman Tempus Fugit (Bruton/UK, 1978). Phonkay space age fuzak! Here the keyboard wiz tears through stellar fantasy lifestyle music, with the terse focus of a falcon and the cheese merchant chops of Rick Wakeman’s little brother (?). Of course, this was on the British late 70’s standard jazz disco funk label Bruton. Here you’ll find plenty of Rhodes massaging, synth-swell galore, and hard clavinet stomping mood pieces that do little to deter your image of spacemen in tight red leather pants, headbands and elbow length white gloves. Run (don’t walk) away slowly.

5. Nino Nardini & Roger Roger Jungle Obsession (Neuilly/France, 1972). Classic moogxotica, though the electronic element is very minimal. This album is a little over-hyped in my opinion, but it’s still a very solid effort. There’s absolutely no weirdo synth filler here (good news for all those weird synth album haters), but elegantly composed lounge jazz with a heavy exotic vibe, befitting the title, and some requisite animal sounds chirping and roaring here and there.

5. Nino Nardini & Roger Roger Jungle Obsession (Neuilly/France, 1972). Classic moogxotica, though the electronic element is very minimal. This album is a little over-hyped in my opinion, but it’s still a very solid effort. There’s absolutely no weirdo synth filler here (good news for all those weird synth album haters), but elegantly composed lounge jazz with a heavy exotic vibe, befitting the title, and some requisite animal sounds chirping and roaring here and there.

6. Armando Sciascia Sea Fantasy (Vedette/Italy, 1972). A stunning, fully formed album of sea themes from symphonic to light jazz. Beautiful orchestration, use of experimental electronics, and most of all there’s an elegant haze over everything.

6. Armando Sciascia Sea Fantasy (Vedette/Italy, 1972). A stunning, fully formed album of sea themes from symphonic to light jazz. Beautiful orchestration, use of experimental electronics, and most of all there’s an elegant haze over everything.

7. Jacques Siroul Midway (Montparnasse 2000/France, 1975) A damn good batch of Morricone-esque groovy instrumental pop, with a little Andre Popp and Serge Gainsbourg tossed in. The rhythm section is beefy and flawless, giving the whole “lounge” factor a total makeover. The harmonica (which I typically don’t care for) makes very frequent appearances on this album, though it is in a melancholic “Midnight Cowboy” vein, and not an annoying bluesy-folk one. There are a couple of corny piano pop concertos, but the zig zag moog and top notch compositions make this one very solid and unique overall. I like to call it “elevator prog”. Yes, I just made that up. This has reissue written all over it, from the crowd-pleasing heavy beats to the smart arrangements and generally great tunes. It’s quickly become one of my favorite albums!

7. Jacques Siroul Midway (Montparnasse 2000/France, 1975) A damn good batch of Morricone-esque groovy instrumental pop, with a little Andre Popp and Serge Gainsbourg tossed in. The rhythm section is beefy and flawless, giving the whole “lounge” factor a total makeover. The harmonica (which I typically don’t care for) makes very frequent appearances on this album, though it is in a melancholic “Midnight Cowboy” vein, and not an annoying bluesy-folk one. There are a couple of corny piano pop concertos, but the zig zag moog and top notch compositions make this one very solid and unique overall. I like to call it “elevator prog”. Yes, I just made that up. This has reissue written all over it, from the crowd-pleasing heavy beats to the smart arrangements and generally great tunes. It’s quickly become one of my favorite albums!

8. Stringtronics Mindbender (Peer-Southern/UK, 1972). This is something of a showcase effort from Barry Forgie, Anthony Mawer, Nino Nardini, and Roger Roger, each displaying their own brand of baroque jazz, with the emphasis on furiously sawed strings. [The first half of Mindbender is a 6-track suite composed by UK library legend Barry Forgie. Recorded in one 3-hour session, it’s a unique psych/funk/baroque exploration that’s made this LP the holy grail of library music collectors for years.]

8. Stringtronics Mindbender (Peer-Southern/UK, 1972). This is something of a showcase effort from Barry Forgie, Anthony Mawer, Nino Nardini, and Roger Roger, each displaying their own brand of baroque jazz, with the emphasis on furiously sawed strings. [The first half of Mindbender is a 6-track suite composed by UK library legend Barry Forgie. Recorded in one 3-hour session, it’s a unique psych/funk/baroque exploration that’s made this LP the holy grail of library music collectors for years.]

9. Joel Vandroogenbroeck Contemporary Pastoral and Ethnic Sounds (Coloursound/Germany, 1980) Ah, what a beaut’! Joel Vandroogenbroeck (aka: VDB Joel) was the main, only consistent member in Brainticket, and on this album he blends the requisite flute with synths and exotica tinged percussion, and comes up with a winner, an almost pop/mainstream approximation of the exotica-library variety. Surely this era of his work is probably lumped in with the new-age crowd (if it is lumped in anywhere at all!), but don’t let such things deter you from a wonderful listen. Majestic peaks of sound wash around, with an Echoplexed flute zipping all over the spectrum. I’m reminded of some long lost Herzog film, as the pastoral post-hippie vibe here bodes well with mid-period Popol Vuh, though in a slightly more synthetic way. There’s even a funky track with sample worthy “breaks” and some nasty clavinet; a seemingly out-of-place track, but it works well. For the most part, Vandroogenbroeck brings an old school krautrock/prog sensibility to the proceedings. Highly recommended!

9. Joel Vandroogenbroeck Contemporary Pastoral and Ethnic Sounds (Coloursound/Germany, 1980) Ah, what a beaut’! Joel Vandroogenbroeck (aka: VDB Joel) was the main, only consistent member in Brainticket, and on this album he blends the requisite flute with synths and exotica tinged percussion, and comes up with a winner, an almost pop/mainstream approximation of the exotica-library variety. Surely this era of his work is probably lumped in with the new-age crowd (if it is lumped in anywhere at all!), but don’t let such things deter you from a wonderful listen. Majestic peaks of sound wash around, with an Echoplexed flute zipping all over the spectrum. I’m reminded of some long lost Herzog film, as the pastoral post-hippie vibe here bodes well with mid-period Popol Vuh, though in a slightly more synthetic way. There’s even a funky track with sample worthy “breaks” and some nasty clavinet; a seemingly out-of-place track, but it works well. For the most part, Vandroogenbroeck brings an old school krautrock/prog sensibility to the proceedings. Highly recommended!

10. Various Artists Under Water Vol. 2: Under and Over the Water Surface (Sonoton/Germany, 1978). Absolutely stunning! This is a top notch collection of spooky yet elegant jazz played with beautiful unease. The woodwinds soar alongside the harps, plucky bass, water logged tubas and trombones, and the brief synth vignettes all add up to a great flow. Fans of moody modal jazz would find much to love here. It’s not too out-there like many conceptual libraries, and is a wonderful, darker cousin to Sven Libaek’s stellar Ron & Val Taylor’s Inner Space, though perhaps a bit more cerebral. It fits into the underwater-as-outer space metaphor quite well – both dark places of mysterious power, stifling vulnerability, and utter loneliness. Standout album track for me is “Wet Suit”. Side one is the mostly jazz section, composed by the duo of Sam Sklair and Oscar Sieben (with one short track by J. Fox & M. Prindy), while side two consists of moody electronic ambience courtesy of Mladen Franko. Very highly recommended!

10. Various Artists Under Water Vol. 2: Under and Over the Water Surface (Sonoton/Germany, 1978). Absolutely stunning! This is a top notch collection of spooky yet elegant jazz played with beautiful unease. The woodwinds soar alongside the harps, plucky bass, water logged tubas and trombones, and the brief synth vignettes all add up to a great flow. Fans of moody modal jazz would find much to love here. It’s not too out-there like many conceptual libraries, and is a wonderful, darker cousin to Sven Libaek’s stellar Ron & Val Taylor’s Inner Space, though perhaps a bit more cerebral. It fits into the underwater-as-outer space metaphor quite well – both dark places of mysterious power, stifling vulnerability, and utter loneliness. Standout album track for me is “Wet Suit”. Side one is the mostly jazz section, composed by the duo of Sam Sklair and Oscar Sieben (with one short track by J. Fox & M. Prindy), while side two consists of moody electronic ambience courtesy of Mladen Franko. Very highly recommended!

For further listening: A few more of my favorites worth tracking down are Walt Rockman’s space-age fairy-tale lullaby, Biology (Sonoton/Germany, 1978), Simon Park’s prog-ish Electric Bird (de Wolfe/UK, 1974), Romolo Grano’s Musica elettronica 1 (Joker/Italy, 1973) featuring superb, scary ambience and bleep-bloop blast, the disturbingly dark Egisto Macchi Voix (Gemelli/Italy, 1970), and the certified classic Cops, Crooks and Spies featuring some moody crime jazz cues by Eddie Warner.

View my complete list of over 350 library records here. —Norm

Do you have a favorite Sound Library composer or title? Share them in the comments field below:

Gene Russell himself made the recordings on Black Jazz happen. His best known album “Talk To My Lady” was self-released via the label and prior to that he had one obscurity lost in the shuffle from Decca. “Talk To My Lady” features a very interesting rework of “My Favorite Things” that alone is worth the price of admission…

Gene Russell himself made the recordings on Black Jazz happen. His best known album “Talk To My Lady” was self-released via the label and prior to that he had one obscurity lost in the shuffle from Decca. “Talk To My Lady” features a very interesting rework of “My Favorite Things” that alone is worth the price of admission… Doug Carn was most prolific for the Oakland label in the early 70s, putting out a release typically once a year. A principal funk and soul player back in the day, his style of jazz-funk was spacey but starkly recorded in contrast to Herbie’s sci-fi releases. Theo’s compilation features his infectious “Trance Dance” track, miles away from his earlier work with Earth Wind and Fire.

Doug Carn was most prolific for the Oakland label in the early 70s, putting out a release typically once a year. A principal funk and soul player back in the day, his style of jazz-funk was spacey but starkly recorded in contrast to Herbie’s sci-fi releases. Theo’s compilation features his infectious “Trance Dance” track, miles away from his earlier work with Earth Wind and Fire. The Awakening produced little but left a big impression in the way that reminds one of the Art Ensemble rhythm section, but not so much Roscoe or Lester, more like a conventional modal horn and reed format. Their work could move from tight and funky to cool. Only two albums were released by Black Jazz before they dissipated.

The Awakening produced little but left a big impression in the way that reminds one of the Art Ensemble rhythm section, but not so much Roscoe or Lester, more like a conventional modal horn and reed format. Their work could move from tight and funky to cool. Only two albums were released by Black Jazz before they dissipated. Calvin Keys is a real heavy hitter from Omaha, Nebraska. As a jazz guitarist he has lent his talents to Ray Charles, Ahmad Jamal, Joe Henderson, Sonny Stitt, and later even M.C. Hammer! His playing is the least free but with plenty of flaying, and he’s confidently subtle in swing. Washes of cymbal crashes are a perfect foil for his pristine R&B spillage.

Calvin Keys is a real heavy hitter from Omaha, Nebraska. As a jazz guitarist he has lent his talents to Ray Charles, Ahmad Jamal, Joe Henderson, Sonny Stitt, and later even M.C. Hammer! His playing is the least free but with plenty of flaying, and he’s confidently subtle in swing. Washes of cymbal crashes are a perfect foil for his pristine R&B spillage. Rudolph Johnson was also a Ray Charles acolyte who made a name for himself as a solid and dedicated tenor sax player. He was virtually unknown outside his crowd in Oakland, where he recorded two Black Jazz LPs. Talented in equal measure, pianist John Barnes and drummer Ray Pounds helped Johnson create maybe the most conventional but tempered music on the label.

Rudolph Johnson was also a Ray Charles acolyte who made a name for himself as a solid and dedicated tenor sax player. He was virtually unknown outside his crowd in Oakland, where he recorded two Black Jazz LPs. Talented in equal measure, pianist John Barnes and drummer Ray Pounds helped Johnson create maybe the most conventional but tempered music on the label. Walter Bishop Jr. may have the highest rep, having played with Charlie Parker, Art Blakey and Stan Getz, but he only managed to put out one album as leader for Black Jazz. One turns out to be enough however: the ever desirable jazz flute is all over this LP, and an unexpected Latin influence presides. That makes it a unique release from this label already on the peripheral.

Walter Bishop Jr. may have the highest rep, having played with Charlie Parker, Art Blakey and Stan Getz, but he only managed to put out one album as leader for Black Jazz. One turns out to be enough however: the ever desirable jazz flute is all over this LP, and an unexpected Latin influence presides. That makes it a unique release from this label already on the peripheral.

A Certain Ratio – The thin boys had a bit of influence on their own and the most consistently solid back catalog. After the drummerless single “All Night Party,” which couldn’t be more dour and Velvet Underground derived, they enlisted proficient funk drummer Donald Johnson and successfully forged post-punk funk. From their cover of Banbarra’s “Shack Up” and the ethereal disco-noir single of “Flight” to the albums “To Each” and “Sextet,” they were quite a formidable, danceable and arty unit. Trumpets sound, whistles blow, Jez Kerr’s bass slaps n’ pops and they even left an impression on the Talking Heads during a tour. Prime.

A Certain Ratio – The thin boys had a bit of influence on their own and the most consistently solid back catalog. After the drummerless single “All Night Party,” which couldn’t be more dour and Velvet Underground derived, they enlisted proficient funk drummer Donald Johnson and successfully forged post-punk funk. From their cover of Banbarra’s “Shack Up” and the ethereal disco-noir single of “Flight” to the albums “To Each” and “Sextet,” they were quite a formidable, danceable and arty unit. Trumpets sound, whistles blow, Jez Kerr’s bass slaps n’ pops and they even left an impression on the Talking Heads during a tour. Prime. Crispy Ambulance – Made up of kids from more of a prog-rock background than punk, Crispy Ambulance albums sound little to nothing like their stablemates. They build expansive sonic environments on albums such as “The Plateau Phase” (which was met with harsh reviews) but their best moment is on the affecting single “Live On A Hot August Night.” That single contains “The Presence,” probably the best slab of Mancunian Kraut-damage you can come across.

Crispy Ambulance – Made up of kids from more of a prog-rock background than punk, Crispy Ambulance albums sound little to nothing like their stablemates. They build expansive sonic environments on albums such as “The Plateau Phase” (which was met with harsh reviews) but their best moment is on the affecting single “Live On A Hot August Night.” That single contains “The Presence,” probably the best slab of Mancunian Kraut-damage you can come across. Section 25 – It’s hard to say which one of these groups had the most critical bashings in the music press, but I bet it was Section 25. After their debut single “Girls Don’t Count,” they went on to record their first album which came very, very late due to Factory taking leisurely time on the album art. “Always Now” was released after Joy Division was long defunct but in retrospect contains a number of great tracks like the PiL-ish “Dirty Disco” and “Be Brave.” The album also has more of a psychedelic feel than anything Factory was producing at the time. Section 25’s brush with success would come later, midway through the 80’s with their future-forward dance track “Looking From a Hilltop.”

Section 25 – It’s hard to say which one of these groups had the most critical bashings in the music press, but I bet it was Section 25. After their debut single “Girls Don’t Count,” they went on to record their first album which came very, very late due to Factory taking leisurely time on the album art. “Always Now” was released after Joy Division was long defunct but in retrospect contains a number of great tracks like the PiL-ish “Dirty Disco” and “Be Brave.” The album also has more of a psychedelic feel than anything Factory was producing at the time. Section 25’s brush with success would come later, midway through the 80’s with their future-forward dance track “Looking From a Hilltop.” The Durutti Column – Making pensive and delicate music, Vini Reilly’s Durutti Column was always a struggling affair. Reilly was a bedsitter, often sick and couldn’t take too many touring commitments, but always produced interesting albums. Arguably, the best run for Vini came when drummer Bruce Mitchell of prog-rock group Greasy Bear joined him for the production of the album “LC.” The Durutti Column would continue on in one form or another, and Vini would eventually lay down guitar work for solo Morrissey output. What a match.

The Durutti Column – Making pensive and delicate music, Vini Reilly’s Durutti Column was always a struggling affair. Reilly was a bedsitter, often sick and couldn’t take too many touring commitments, but always produced interesting albums. Arguably, the best run for Vini came when drummer Bruce Mitchell of prog-rock group Greasy Bear joined him for the production of the album “LC.” The Durutti Column would continue on in one form or another, and Vini would eventually lay down guitar work for solo Morrissey output. What a match. Swamp Children / Kalima – A sort of latin jazz side project by members of A Certain Ratio and siblings Ann and Tony Quigley (names that seem to personify white people jazz), projects Swamp Children and later Kalima made swinging and sophisticated dance music with a modern spin. If it wasn’t for the obvious ACR connection, they would otherwise be lost in the shuffle. That would be a shame, because they put out some great albums, especially “So Hot” and the “Four Songs” EP, respectively.

Swamp Children / Kalima – A sort of latin jazz side project by members of A Certain Ratio and siblings Ann and Tony Quigley (names that seem to personify white people jazz), projects Swamp Children and later Kalima made swinging and sophisticated dance music with a modern spin. If it wasn’t for the obvious ACR connection, they would otherwise be lost in the shuffle. That would be a shame, because they put out some great albums, especially “So Hot” and the “Four Songs” EP, respectively. Marcel King – Once the lead singer of popular soul act Sweet Sensation, by the time Marcel had fallen in with Factory, hits were not on his side. Sweet Sensation also had an ACR connection, with members of the group being older siblings of Donald Johnson. Rob Gretton had high hopes for Marcel’s only output for Factory, “Reach For Love,” but it failed to connect with most Factory followers of the day. Marcel had turned into a tragic figure through heroin addiction and homelessness by the time the record was cut, but the single is still a great slice of electro-soul.

Marcel King – Once the lead singer of popular soul act Sweet Sensation, by the time Marcel had fallen in with Factory, hits were not on his side. Sweet Sensation also had an ACR connection, with members of the group being older siblings of Donald Johnson. Rob Gretton had high hopes for Marcel’s only output for Factory, “Reach For Love,” but it failed to connect with most Factory followers of the day. Marcel had turned into a tragic figure through heroin addiction and homelessness by the time the record was cut, but the single is still a great slice of electro-soul. James – When I first heard the track “Hymn From a Village” on my Factory comp, it was probably one of my favorites. It also doesn’t seem to fit anywhere; it’s not really forward thinking pop, still angular but in an emerging indie sound kind of way before it was a norm… Check out their “Village Fire” EP for greater understanding. James became semi-well known in the U.S. thanks to the inclusion of their song “Laid” on the first American Pie movie… Obviously a way different group by that point. What a weird career arc.

James – When I first heard the track “Hymn From a Village” on my Factory comp, it was probably one of my favorites. It also doesn’t seem to fit anywhere; it’s not really forward thinking pop, still angular but in an emerging indie sound kind of way before it was a norm… Check out their “Village Fire” EP for greater understanding. James became semi-well known in the U.S. thanks to the inclusion of their song “Laid” on the first American Pie movie… Obviously a way different group by that point. What a weird career arc. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark – Another band that got big and made it into a Motion Picture Soundtrack (Pretty in Pink, alongside Manchester groups New Order, The Smiths), OMD put out their very first single “Electricity” with Factory and were also produced by Hannett. In this case the production worked well with this definitive New Wave group, but apparently they didn’t care much for it. Later, at a Factory reunion show of sorts called G-Mex, OMD stripped down to a duo and only used their own original equipment to perform a thoughtful retro set for Manchester crowds… This was after their massive pop success of “(If You Leave)” and to their chagrin, they were introduced to the crowd as “two rich bastards from L.A.” by popular music scribe Paul Morley. Their association with Factory didn’t really continue much after that.

Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark – Another band that got big and made it into a Motion Picture Soundtrack (Pretty in Pink, alongside Manchester groups New Order, The Smiths), OMD put out their very first single “Electricity” with Factory and were also produced by Hannett. In this case the production worked well with this definitive New Wave group, but apparently they didn’t care much for it. Later, at a Factory reunion show of sorts called G-Mex, OMD stripped down to a duo and only used their own original equipment to perform a thoughtful retro set for Manchester crowds… This was after their massive pop success of “(If You Leave)” and to their chagrin, they were introduced to the crowd as “two rich bastards from L.A.” by popular music scribe Paul Morley. Their association with Factory didn’t really continue much after that. 52nd Street – Without too much thought, either. Mostly known for the electro-funk single “Cool As Ice,” which has since ended up on a ton of compilations, my fave release from this jazz-funk ensemble has to be “Look Into My Eyes” b/w “Express.” This piece of vinyl has a great infectious vibe that is good natured and seems like it could have been played out at the Paradise Garage or something… 52nd Street also had (surprise!) an ACR connection by hiring Donald Johnson’s younger brother to perform bass duties. Due to that lineage, 52nd Street fell into Rob Gretton’s hands and into Factory’s convoluted history.

52nd Street – Without too much thought, either. Mostly known for the electro-funk single “Cool As Ice,” which has since ended up on a ton of compilations, my fave release from this jazz-funk ensemble has to be “Look Into My Eyes” b/w “Express.” This piece of vinyl has a great infectious vibe that is good natured and seems like it could have been played out at the Paradise Garage or something… 52nd Street also had (surprise!) an ACR connection by hiring Donald Johnson’s younger brother to perform bass duties. Due to that lineage, 52nd Street fell into Rob Gretton’s hands and into Factory’s convoluted history.

The first wave of music resulting from those historical forces is what most people know as Rockabilly, and one cannot seriously examine that generation without discussing Sun Records. Sun, the brainchild of Sam Phillips, was a Memphis recording studio founded in the early 1950s. Phillips is famous for recording and producing work by Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis among others, and he is credited with creating the original Rock and Roll sound. “Rocket 88”, a song often cited as the first Rock and Roll (and first Rockabilly) song was recorded at Sun, and in some ways represents the racial and musical divisions of the time. Though Sun is most noted for work with white musicians who incorporated a black sound, African-American artist Jackie Brenston first recorded “Rocket 88” at Sun as part of Ike Turner’s Kings of Rhythm band. Interestingly, though Sam Phillips recorded the song, he gave it to Chess, a dominantly black label, for release.

The first wave of music resulting from those historical forces is what most people know as Rockabilly, and one cannot seriously examine that generation without discussing Sun Records. Sun, the brainchild of Sam Phillips, was a Memphis recording studio founded in the early 1950s. Phillips is famous for recording and producing work by Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, and Jerry Lee Lewis among others, and he is credited with creating the original Rock and Roll sound. “Rocket 88”, a song often cited as the first Rock and Roll (and first Rockabilly) song was recorded at Sun, and in some ways represents the racial and musical divisions of the time. Though Sun is most noted for work with white musicians who incorporated a black sound, African-American artist Jackie Brenston first recorded “Rocket 88” at Sun as part of Ike Turner’s Kings of Rhythm band. Interestingly, though Sam Phillips recorded the song, he gave it to Chess, a dominantly black label, for release. Other notable artists of the time included Gene Vincent, most noted perhaps for his hit “Be-Bop-a-Lula”, Eddie Cochran, whose “20 Flight Rock” was made famous in the film “The Girl Can’t Help It” and whose “Summertime Blues” was a hit for both him and later The Who, and Bill Haley, who also recorded and released a version of “Rocket 88”, and who would later score hits such as “Rock Around the Clock” and a version of “Shake, Rattle, and Roll”. A bit of sleuthing into any of these artists, or others such as Chuck Berry, Billy Lee Riley, Joe Bennett, or Bo Diddley, can lead the interested newbie to scores of others from those early years.

Other notable artists of the time included Gene Vincent, most noted perhaps for his hit “Be-Bop-a-Lula”, Eddie Cochran, whose “20 Flight Rock” was made famous in the film “The Girl Can’t Help It” and whose “Summertime Blues” was a hit for both him and later The Who, and Bill Haley, who also recorded and released a version of “Rocket 88”, and who would later score hits such as “Rock Around the Clock” and a version of “Shake, Rattle, and Roll”. A bit of sleuthing into any of these artists, or others such as Chuck Berry, Billy Lee Riley, Joe Bennett, or Bo Diddley, can lead the interested newbie to scores of others from those early years. As the new sounds of the 1960s began to dominate the airwaves, Rockabilly faded into the background, or rather was incorporated into the styles of new chart toppers such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, both of whom were deeply influenced by early American Rockabilly. Numerous artists continued to play “pure” rockabilly, however, and the 1970s and 80s brought what some would consider the second wave. Artists such as Sleepy LaBeef (pictured), Ronnie Dawson, and Ray Campi led the pack, though none were new to the scene. Sleep LaBeef, for example, had been recording since the 1950s, and joined the Sun roster in 1970. His career exemplified the “big in Japan” element that sometimes characterized rockabilly of the era. LaBeef’s popularity increased in Europe while never cracking the charts in the United States, even as nostalgia for the music began to emerge in mainstream American media with films such as “American Graffiti” and the television show “Happy Days”.

As the new sounds of the 1960s began to dominate the airwaves, Rockabilly faded into the background, or rather was incorporated into the styles of new chart toppers such as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, both of whom were deeply influenced by early American Rockabilly. Numerous artists continued to play “pure” rockabilly, however, and the 1970s and 80s brought what some would consider the second wave. Artists such as Sleepy LaBeef (pictured), Ronnie Dawson, and Ray Campi led the pack, though none were new to the scene. Sleep LaBeef, for example, had been recording since the 1950s, and joined the Sun roster in 1970. His career exemplified the “big in Japan” element that sometimes characterized rockabilly of the era. LaBeef’s popularity increased in Europe while never cracking the charts in the United States, even as nostalgia for the music began to emerge in mainstream American media with films such as “American Graffiti” and the television show “Happy Days”. One European who was strongly impressed by Rockabilly was Ronnie Weiser (pictured), who would eventually move to the United States and form Rollin’ Rock Records, a label devoted to the sound. Weiser, a seminal figure in the “rebirth” of Rockabilly, reissued numerous recordings from the early days, and eventually began to release new material, including music from The Blasters, who became part of a larger collection of Rockabilly artists who would thrive in the 1980s.

One European who was strongly impressed by Rockabilly was Ronnie Weiser (pictured), who would eventually move to the United States and form Rollin’ Rock Records, a label devoted to the sound. Weiser, a seminal figure in the “rebirth” of Rockabilly, reissued numerous recordings from the early days, and eventually began to release new material, including music from The Blasters, who became part of a larger collection of Rockabilly artists who would thrive in the 1980s. 1980s Rockabilly was often marketed as a kind of New Wave music, and it was during this era that Rockabilly began to split into its own set of sub-genres. The Blasters continued to thrive as part of the L.A. Punk scene, and a cover of their song “Marie, Marie” was a U.K. hit for Welsh artist Shakin’ Stevens. The Stray Cats (pictured) had enormous mainstream success with hits such as “Stray Cat Strut” and “Rock This Town”, though interestingly they had to move to England in order to get their first big break. Other bands of note from the time included The Polecats and The Rockats. Sub-genres, born of a blend of Rockabilly and other genres including Punk, Garage, and Surf, would birth new artists such as The Reverend Horton Heat, The Cramps, and Jason and the Scorchers. Numerous disagreements have since ensued regarding which of these and other artists are or are not authentic Rockabilly, who veered too much toward pop, who sold out, and so on. While occasionally divisive, the fact there was and is a large enough body of work to argue about speaks to the strength and permanence of the Rockabilly sound itself.

1980s Rockabilly was often marketed as a kind of New Wave music, and it was during this era that Rockabilly began to split into its own set of sub-genres. The Blasters continued to thrive as part of the L.A. Punk scene, and a cover of their song “Marie, Marie” was a U.K. hit for Welsh artist Shakin’ Stevens. The Stray Cats (pictured) had enormous mainstream success with hits such as “Stray Cat Strut” and “Rock This Town”, though interestingly they had to move to England in order to get their first big break. Other bands of note from the time included The Polecats and The Rockats. Sub-genres, born of a blend of Rockabilly and other genres including Punk, Garage, and Surf, would birth new artists such as The Reverend Horton Heat, The Cramps, and Jason and the Scorchers. Numerous disagreements have since ensued regarding which of these and other artists are or are not authentic Rockabilly, who veered too much toward pop, who sold out, and so on. While occasionally divisive, the fact there was and is a large enough body of work to argue about speaks to the strength and permanence of the Rockabilly sound itself. And lest you think Rockabilly is only a boys’ town, rest assured the ladies have been making their mark from the beginning. A woman named Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton recorded the original version of “Hound Dog”, after all, later made famous by Elvis Presley. Wanda Jackson (pictured), known as the “female Elvis” has been working her distinct growl and hiccup since the early 1950s. Jack White, a devoted Jackson fan, recently worked with her on the 2011 album, “The Party Ain’t Over”, for which she toured steadily as the opening act for Adele. Other women from the early years include Barbara Pittman and Janis Martin, and there are numerous successful modern artists such as Rosie Flores, Marti Brom, and Kim Lenz. Lisa Pankratz, one of the most respected and in-demand Rockabilly drummers of the present day, is a woman as well.

And lest you think Rockabilly is only a boys’ town, rest assured the ladies have been making their mark from the beginning. A woman named Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton recorded the original version of “Hound Dog”, after all, later made famous by Elvis Presley. Wanda Jackson (pictured), known as the “female Elvis” has been working her distinct growl and hiccup since the early 1950s. Jack White, a devoted Jackson fan, recently worked with her on the 2011 album, “The Party Ain’t Over”, for which she toured steadily as the opening act for Adele. Other women from the early years include Barbara Pittman and Janis Martin, and there are numerous successful modern artists such as Rosie Flores, Marti Brom, and Kim Lenz. Lisa Pankratz, one of the most respected and in-demand Rockabilly drummers of the present day, is a woman as well. Today, Rockabilly is thriving around the world, and though none of today’s artists are breaking through to crack the auto-tune dominated modern charts, numerous bands record and tour successfully for a wide international audience of devoted fans. Notable artists of the last two decades include High Noon, Big Sandy (pictured), Deke Dickerson, Ray Condo, and literally hundreds – if not thousands – of lesser known acts around the globe, many of which are connected in an intimate and tightly woven network that extends from the former nations of the Soviet Bloc to South America, and new voices steadily continue to enter the ring. Check out JD McPherson and Lanie Lane for a start.

Today, Rockabilly is thriving around the world, and though none of today’s artists are breaking through to crack the auto-tune dominated modern charts, numerous bands record and tour successfully for a wide international audience of devoted fans. Notable artists of the last two decades include High Noon, Big Sandy (pictured), Deke Dickerson, Ray Condo, and literally hundreds – if not thousands – of lesser known acts around the globe, many of which are connected in an intimate and tightly woven network that extends from the former nations of the Soviet Bloc to South America, and new voices steadily continue to enter the ring. Check out JD McPherson and Lanie Lane for a start.

Dr. John In The Right Place (1973) Dr. John’s early “Night Tripper” recordings are classics of n’awlins hoodoo spook, fully evoking the hallucinogenic world of the crazed Creole witchdoctor he built his image on. But after four albums of this kind of dark mojo, the Dr. understandably grew curious as to how the other, day-light-dwelling half lived. Initiating this move with the previous year’s Gumbo, Toussaint and The Meters helped bring it all together on In The Right Place, stirring in an extra dose of traditional New Orleans R&B and funk that helps propel and lift the songs in ways he’d never dared before. While the mood is definitely brighter, some of the signature touches of his early recordings remain, like the moody tribal hand-drumming that pops up on the slower cuts. And then there’s that voice – few things exude the charm and menace of the Deep South like Dr. John’s slurred creole growl – a tool no amount of polish can completely neutralize. This one catches the key players of the scene at the height of their powers, bringing the untouchable sound of The Meters and Toussaint’s stellar horn and songwriting arrangements together with one of the more singular voices of their generation.

Dr. John In The Right Place (1973) Dr. John’s early “Night Tripper” recordings are classics of n’awlins hoodoo spook, fully evoking the hallucinogenic world of the crazed Creole witchdoctor he built his image on. But after four albums of this kind of dark mojo, the Dr. understandably grew curious as to how the other, day-light-dwelling half lived. Initiating this move with the previous year’s Gumbo, Toussaint and The Meters helped bring it all together on In The Right Place, stirring in an extra dose of traditional New Orleans R&B and funk that helps propel and lift the songs in ways he’d never dared before. While the mood is definitely brighter, some of the signature touches of his early recordings remain, like the moody tribal hand-drumming that pops up on the slower cuts. And then there’s that voice – few things exude the charm and menace of the Deep South like Dr. John’s slurred creole growl – a tool no amount of polish can completely neutralize. This one catches the key players of the scene at the height of their powers, bringing the untouchable sound of The Meters and Toussaint’s stellar horn and songwriting arrangements together with one of the more singular voices of their generation. Labelle Nightbirds (1974) Though they’re rarely mentioned with the same esteem held for their predecessors (Aretha Franklin, The Supremes) or their direct descendants, Labelle effectively built the bridge between the two. Their high-energy, funky modernization of the classic soul/R&B girl group sound looked forward to the disco inferno of Donna Summer as much as it did the unhinged ’90’s diva-isms of En Vogue or TLC. Notable for the presence of the Toussaint-penned hit and calling-card, “Lady Marmalade” Nightbirds is probably their best album through and through, thanks to Toussaint’s spacious production and arrangements and the lithe maneuvering of The Meters in the pocket funk support. Patti Labelle’s move into a more mainstream solo career sometimes overshadows just how great Labelle were for awhile, especially Nona Hendryx, who wrote most of the group’s material and was responsible for their increasingly flamboyant attitude and image. Along with P-Funk, Labelle were at the vanguard of Nubian-space-glam, predicting the outre stylings of Kool Keith, Outkast, and any number of modern Hiphop/R&B divas.

Labelle Nightbirds (1974) Though they’re rarely mentioned with the same esteem held for their predecessors (Aretha Franklin, The Supremes) or their direct descendants, Labelle effectively built the bridge between the two. Their high-energy, funky modernization of the classic soul/R&B girl group sound looked forward to the disco inferno of Donna Summer as much as it did the unhinged ’90’s diva-isms of En Vogue or TLC. Notable for the presence of the Toussaint-penned hit and calling-card, “Lady Marmalade” Nightbirds is probably their best album through and through, thanks to Toussaint’s spacious production and arrangements and the lithe maneuvering of The Meters in the pocket funk support. Patti Labelle’s move into a more mainstream solo career sometimes overshadows just how great Labelle were for awhile, especially Nona Hendryx, who wrote most of the group’s material and was responsible for their increasingly flamboyant attitude and image. Along with P-Funk, Labelle were at the vanguard of Nubian-space-glam, predicting the outre stylings of Kool Keith, Outkast, and any number of modern Hiphop/R&B divas. Wild Tchoupitoulas (1976) Tchoupitoulas St. is an ancient New Orleans thouroughfare, named for the Native American Indian tribe who cut it’s original path along the Mississippi as a trade route. The deep history of the name bleeds through this joyful and unique album at every instance, imbuing the proceedings with a real sense of place, and the people who inhabit it. The band was made up of members of The Meters and their extended family – representatives of the nearly-extinct Tchoupitoulas tribe – and produced by Allen Toussaint. In terms of definitive New Orleans records, this ranks with the best work of Dr. John in the way it wholly embodies the spirit of the city, taking the Meters signature groove and riding it through the streets of the Mardi Gras parade without a care in the world. You could be sipping a cup of dirty Mississippi River water and still be in a good mood when the needle drops on this one.

Wild Tchoupitoulas (1976) Tchoupitoulas St. is an ancient New Orleans thouroughfare, named for the Native American Indian tribe who cut it’s original path along the Mississippi as a trade route. The deep history of the name bleeds through this joyful and unique album at every instance, imbuing the proceedings with a real sense of place, and the people who inhabit it. The band was made up of members of The Meters and their extended family – representatives of the nearly-extinct Tchoupitoulas tribe – and produced by Allen Toussaint. In terms of definitive New Orleans records, this ranks with the best work of Dr. John in the way it wholly embodies the spirit of the city, taking the Meters signature groove and riding it through the streets of the Mardi Gras parade without a care in the world. You could be sipping a cup of dirty Mississippi River water and still be in a good mood when the needle drops on this one. Allen Touissant Southern Nights (1975) Toussaint seemingly gave some of his best stuff away, perhaps having the intuition (and humble nature) to know when a song was just right for someone else. No matter how many times they’re covered in a House Of Blues revue, Lee Dorsey’s versions of “Working In A Coalmine” and “Get Out Of My Life Woman” will always be the definitive ones. However, like any good man-behind-the-scenes, Toussaint managed to hold back some of his best material for himself. All of his solo albums from this period are more than worthwhile, but Southern Nights may be the crowning achievement of his solo oeuvre. The record employs some of the same tools that made his hand in The Meters and Dr. John’s output of the period so evident while side-stepping the confines of the typical soul-funk record, with laid-back, soul-baring deliveries that roll as much as they groove. He filters his vocals through what sounds like a Hammond Leslie on many of the tracks, contributing to the humid, swampy effect of the proceedings, and transporting us into the otherworldly night scene depicted on the cover. Glen Campbell popularized the title track, but Toussaint’s performance of it remains one of the more moving things ever committed to tape, and a convincing, sublime love letter to New Orleans and The South.

Allen Touissant Southern Nights (1975) Toussaint seemingly gave some of his best stuff away, perhaps having the intuition (and humble nature) to know when a song was just right for someone else. No matter how many times they’re covered in a House Of Blues revue, Lee Dorsey’s versions of “Working In A Coalmine” and “Get Out Of My Life Woman” will always be the definitive ones. However, like any good man-behind-the-scenes, Toussaint managed to hold back some of his best material for himself. All of his solo albums from this period are more than worthwhile, but Southern Nights may be the crowning achievement of his solo oeuvre. The record employs some of the same tools that made his hand in The Meters and Dr. John’s output of the period so evident while side-stepping the confines of the typical soul-funk record, with laid-back, soul-baring deliveries that roll as much as they groove. He filters his vocals through what sounds like a Hammond Leslie on many of the tracks, contributing to the humid, swampy effect of the proceedings, and transporting us into the otherworldly night scene depicted on the cover. Glen Campbell popularized the title track, but Toussaint’s performance of it remains one of the more moving things ever committed to tape, and a convincing, sublime love letter to New Orleans and The South. The Meters Struttin’ (1970) It would be remiss (and nearly impossible) to write about New Orleans music in the ’70’s without mentioning The Meters own studio albums – though so much ink has already been devoted to this pursuit, we chose not to single one out here. They are the building blocks of all the aforementioned classic albums, and a bunch of other songs you’ve heard and loved without knowing why (it’s The Meters). Struttin’ is a highlight, but it’s hard to go wrong with any of their early ’70’s albums.

The Meters Struttin’ (1970) It would be remiss (and nearly impossible) to write about New Orleans music in the ’70’s without mentioning The Meters own studio albums – though so much ink has already been devoted to this pursuit, we chose not to single one out here. They are the building blocks of all the aforementioned classic albums, and a bunch of other songs you’ve heard and loved without knowing why (it’s The Meters). Struttin’ is a highlight, but it’s hard to go wrong with any of their early ’70’s albums.

The Dream Syndicate The Days of Wine and Roses (1982). Without a doubt the most commercially viable of the Paisley Underground fleet, the Dream Syndicate were the Trojan horse that snuck everyone else into the party. Not that most of their brethren would have anything approaching mainstream success, but many would land major label contracts and a degree of recognition, at least for a time. The Days of Wine and Roses has endured for good reason – it was, pound for pound, one of the more bulletproof releases from the Paisley scene, or any of the era in general. Of course it helped that they were doing something pretty far out-of-line with the times – reviving primitive guitar meltdowns and folk melodies in the age of New Romanticism and Eye Of The Tiger.

The Dream Syndicate The Days of Wine and Roses (1982). Without a doubt the most commercially viable of the Paisley Underground fleet, the Dream Syndicate were the Trojan horse that snuck everyone else into the party. Not that most of their brethren would have anything approaching mainstream success, but many would land major label contracts and a degree of recognition, at least for a time. The Days of Wine and Roses has endured for good reason – it was, pound for pound, one of the more bulletproof releases from the Paisley scene, or any of the era in general. Of course it helped that they were doing something pretty far out-of-line with the times – reviving primitive guitar meltdowns and folk melodies in the age of New Romanticism and Eye Of The Tiger. Rain Parade Emergency Third Rail Power Trip/Explosions In The Glass Palace (1983/1984). Although many of the Paisley Underground’s main players would manage to sustain careers in some form or other, The Rain Parade’s Steven Roback was perhaps the only figure who would go on to eclipse the success and popularity of his PU-era acts. Growing up in the age of Mazzy Star, it would be years before I realized Roback had been quietly refining his hazy whisper-core for a decade before the commercial breakthrough of “Fade Into You.” Hope Sandoval would first appear in later incarnations of Opal, but it was with Rain Parade that Roback began crafting his strain of hushed psychedelic pop that would become so influential years down the line. It’s no secret that a lot of pop music from this era did not age well, but Rain Parade’s modern take on the dark side of psychedelia manages to hold up well, even among their Paisley peers.

Rain Parade Emergency Third Rail Power Trip/Explosions In The Glass Palace (1983/1984). Although many of the Paisley Underground’s main players would manage to sustain careers in some form or other, The Rain Parade’s Steven Roback was perhaps the only figure who would go on to eclipse the success and popularity of his PU-era acts. Growing up in the age of Mazzy Star, it would be years before I realized Roback had been quietly refining his hazy whisper-core for a decade before the commercial breakthrough of “Fade Into You.” Hope Sandoval would first appear in later incarnations of Opal, but it was with Rain Parade that Roback began crafting his strain of hushed psychedelic pop that would become so influential years down the line. It’s no secret that a lot of pop music from this era did not age well, but Rain Parade’s modern take on the dark side of psychedelia manages to hold up well, even among their Paisley peers. True West Drifters (1984). One of the more overlooked bands in the PU orbit, True West approximated what The Church might have sounded like with a touch of the great plains (via the Central Valley) stirred in to taste. Though the early lineup (featuring songwriter Russ Tolman) didn’t last long, they would manage to squeeze out a couple of great EPs and this superlative full-length debut. While Tolman and many of his peers from the Paisley scene would go further down the wagon trail of Americana and Alt-Country/No-Depression, Drifters remains the perfect balance of crisp, sparkling songwriting, with a kiss of twang felt in the flourishes of the occasional plangent guitar lead and brooding lyricism. Fans of early Robyn Hitchcock or The Go-Betweens darker material should investigate post-haste.

True West Drifters (1984). One of the more overlooked bands in the PU orbit, True West approximated what The Church might have sounded like with a touch of the great plains (via the Central Valley) stirred in to taste. Though the early lineup (featuring songwriter Russ Tolman) didn’t last long, they would manage to squeeze out a couple of great EPs and this superlative full-length debut. While Tolman and many of his peers from the Paisley scene would go further down the wagon trail of Americana and Alt-Country/No-Depression, Drifters remains the perfect balance of crisp, sparkling songwriting, with a kiss of twang felt in the flourishes of the occasional plangent guitar lead and brooding lyricism. Fans of early Robyn Hitchcock or The Go-Betweens darker material should investigate post-haste. Game Theory Real Nighttime (1985). Scott Miller’s Game Theory were outliers in a scene already on the fringes. They came up in the same circuit, and shared bills and basic aesthetic choices with many of the Paisley school, but were closer to a traditional power pop band in execution. I know – the words “power pop” are a kiss of death for some of you out there, but don’t let that scare you off. Miller and his rotating cast of players churned out some of the most infectious albums of the era – songs stacked with hooks, each catchier than the one that preceded it. No one talks about it, but there’s no way Real Nighttime and The Big Shot Chronicles were not formative influences on The New Pornographers and their ilk.

Game Theory Real Nighttime (1985). Scott Miller’s Game Theory were outliers in a scene already on the fringes. They came up in the same circuit, and shared bills and basic aesthetic choices with many of the Paisley school, but were closer to a traditional power pop band in execution. I know – the words “power pop” are a kiss of death for some of you out there, but don’t let that scare you off. Miller and his rotating cast of players churned out some of the most infectious albums of the era – songs stacked with hooks, each catchier than the one that preceded it. No one talks about it, but there’s no way Real Nighttime and The Big Shot Chronicles were not formative influences on The New Pornographers and their ilk. Opal Early Recordings (1989). Although some of it came out under the Clay Allison moniker, most of this material didn’t see wide release until well after the departure of Kendra Smith, who, starting with The Dream Syndicate, appeared to be making a tradition out of quitting bands just when they were peaking. Though a lot of people swear by Happy Nightmare Baby (recorded later with Hope Sandoval), this material is perhaps the perfect literal embodiment of the enigmatic darkness that a term like “Paisley Underground” implies. The template for Mazzy Star is even more in evidence here, with Roback and Smith’s dark torch songs stretching out into extended, loose-limbed psych/folk jams without warning. If The Days Of Wine And Roses was a modern interpretation of White Light/White Heat’s pathos, Opal’s early movements were the equivalent of the third VU album – candlelit meditations of uninhibited beauty and longing.

Opal Early Recordings (1989). Although some of it came out under the Clay Allison moniker, most of this material didn’t see wide release until well after the departure of Kendra Smith, who, starting with The Dream Syndicate, appeared to be making a tradition out of quitting bands just when they were peaking. Though a lot of people swear by Happy Nightmare Baby (recorded later with Hope Sandoval), this material is perhaps the perfect literal embodiment of the enigmatic darkness that a term like “Paisley Underground” implies. The template for Mazzy Star is even more in evidence here, with Roback and Smith’s dark torch songs stretching out into extended, loose-limbed psych/folk jams without warning. If The Days Of Wine And Roses was a modern interpretation of White Light/White Heat’s pathos, Opal’s early movements were the equivalent of the third VU album – candlelit meditations of uninhibited beauty and longing.

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae.

Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse (1982). Gregory is a good gateway for people who don’t technically have a problem with Bob Marley, but are soured by the over-saturation of his image/music in popular culture. Gregory “The Cool Ruler” was blessed with pipes every bit as strong and expressive as Marley’s, with a natural gift for melody, and a voice smooth and sweet enough to buff out the scratches on your Minibus. Mr. Isaacs was pre-occupied with the fairer sex as much as themes of roots and culture, so it’s not all ganja anthems and Hail Selassie (although there is some of that). Much of his material revolves around classic lover’s themes, the bedrock of all pop music, and a potential lifeline for those looking for a little tunefulness and romance with their Reggae. Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music.

Rhythm & Sound With The Artists (Compilation, 2003). Rhythm & Sound are Berliners who got their start in the ’90’s making minimal, dubby Techno under the quietly influential Basic Channel moniker. Their Rhythm & Sound project surgically removes the 4/4 spine from their productions, swapping it out for Reggae’s ubiquitous backbeat, and stripping the music down to it’s barest essentials, leaving only the slightest suggestion of Reggae’s pulsating undercurrent. With The Artists sees them voicing their tracks with Reggae legends like the Love Joys and Cornel Campbell, effectively forging a bridge from Reggae’s past to it’s potential future. The results are a spectral, midnight burial dub that sounds unlike anything else in the body of Reggae or Electronic music. Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today.

Keith Hudson Flesh Of My Skin: Blood Of My Blood (1975). One of the more interesting and idiosyncratic figures in the genre’s history, Hudson was a former dentist who became something of a Reggae renaissance man – producing, playing, and singing in numerous iterations. In 1974 he released Flesh Of My Skin, Blood Of My Blood – one of the first deliberately conceived “albums” (i.e., not a collection of singles, etc) in Reggae history, and a concept album to boot. Known as the “Dark Prince Of Reggae,” Hudson had a raspy, off-pitch delivery, which works perfectly with the spooky, fog-cloaked production of this otherworldly work that occasionally recalls what Dr. John’s “Gris-Gris” would have sounded like if he’d been Jamaican, not just Creole. A landmark album that still sounds way ahead of it’s time today. Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision.

Augustus Pablo East Of The River Nile (1977). In my experience, the music of Augustus Pablo has proven to be a soothing balm to the ear of many a Reggae-dissonant. Something about the sound of the melodica, Pablo’s trademark instrument, succeeds in enchanting the wary listener into blissful submission. The alien sound of the melodica (an instrument not often heard in Reggae, or music period) floats over the mix like vapor, carrying the intrigue of the unfamiliar while triggering a faint nostalgia for Morricone-soundtracked Westerns. Pablo is best-known for his late-seventies melodica records, but was also a multi-talented musician and producer, playing on barrels of classic sessions and continuing to produce innovative work through the ’90’s. Pressure Sounds recently released a selection of his digital-era recordings, which comes highly recommended to anyone looking to delve deeper into his maverick vision. Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

Dadawah Peace And Love (1974). Dadawah’s “Peace And Love” is the crowning achievement of one Ras Michael, an artist who has released numerous recordings under the latter handle. Michael concentrates on the nyabinghi strain of Reggae – traditional Rastafarian spiritual music, roughly equivalent to Mississippi hill country Blues in it’s rawness and purity of vision. The unique sound of the Dadawah record arises from a stripped-down rhythmic core of hand-drum and bass, eschewing the standard drum kit and rhythm-guitar backbeat of Reggae. When guitar does creep into the mix, it’s in the form of improvised, bluesy interjections, never settling on a fixed melody or pattern. The album consists of four slow-building, hazed-out songs, often running into the 10-12 minute mark – all of it soaking in a vat of reverb. A deeply expansive and singular record that will melt the mind of anyone into Psychedelia, Krautrock, Primitive Blues, or even Spiritual Jazz.

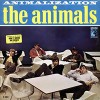

The Animals Animalization (1966) Aside from the Soft Machine (see below) Wilson produced very few British acts. Recorded as the original line-up was beginning to splinter, Wilson was still able to coax a brilliant performance out of Eric Burdon and his cohort. The raw bluesiness of their earlier work is still here, but with an added dimension of psychedelia, a style that Burdon would fully embrace in the next incarnation of the Animals and in his later solo work.

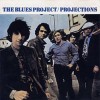

The Animals Animalization (1966) Aside from the Soft Machine (see below) Wilson produced very few British acts. Recorded as the original line-up was beginning to splinter, Wilson was still able to coax a brilliant performance out of Eric Burdon and his cohort. The raw bluesiness of their earlier work is still here, but with an added dimension of psychedelia, a style that Burdon would fully embrace in the next incarnation of the Animals and in his later solo work. The Blues Project Projections (1966) Though counting Al Kooper as a member, The Blues Project’s ambitious amalgam of folk, blues, and jazz initially hindered their efforts to achieve a musical identity. It took a person like Wilson to recognize the band’s eclectic influences and diverse skills and make them all flow together, and he did just that on this underrated album. One of their most popular songs, “Flute Thing” (a hit during the early days of underground FM radio) is here, but unfortunately, their other one, “No Time like the Right Time” (which eventually appeared on the original

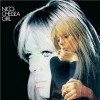

The Blues Project Projections (1966) Though counting Al Kooper as a member, The Blues Project’s ambitious amalgam of folk, blues, and jazz initially hindered their efforts to achieve a musical identity. It took a person like Wilson to recognize the band’s eclectic influences and diverse skills and make them all flow together, and he did just that on this underrated album. One of their most popular songs, “Flute Thing” (a hit during the early days of underground FM radio) is here, but unfortunately, their other one, “No Time like the Right Time” (which eventually appeared on the original  Nico Chelsea Girl (1967) Wilson worked with members of the Velvet Underground (see below) before, but Chelsea Girl is quite different than anything else he did with them or anyone else. The level of backing talent on the record is astounding; Lou Reed, John Cale, and Jackson Browne all sat in on the sessions. Yet the musical accompaniment is sparse and anonymous, the perfect foil for Nico’s ghostly delivery of its dark subject matter (drugs, betrayal, death). Chelsea Girls marks one of the few times when Wilson artistically intervened, insisting that strings and flute be added to some of the songs. Nico despised and disowned the finished product. Still,

Nico Chelsea Girl (1967) Wilson worked with members of the Velvet Underground (see below) before, but Chelsea Girl is quite different than anything else he did with them or anyone else. The level of backing talent on the record is astounding; Lou Reed, John Cale, and Jackson Browne all sat in on the sessions. Yet the musical accompaniment is sparse and anonymous, the perfect foil for Nico’s ghostly delivery of its dark subject matter (drugs, betrayal, death). Chelsea Girls marks one of the few times when Wilson artistically intervened, insisting that strings and flute be added to some of the songs. Nico despised and disowned the finished product. Still,  The Velvet Underground White Light White Heat (1968) Debate rages over Wilson’s level of involvement with the first Velvet Underground record. Though Andy Warhol was given full credit for production duties (most likely for financial reasons,) Wilson is said to have produced at least four of its tracks and to have supervised the final mix-down of the whole thing. Whatever the case, he was brought back as full-on producer for this sophomore effort, the most challenging and uncompromising in the band’s catalog. Having worked with the Velvets before, Wilson probably knew it best to leave them to their own devices. Besides, he had other things going on anyway. Guitarist Sterling Morrison once recounted that Wilson, ever the lady’s man, spent most of the studio time entertaining a rotating roster of beautiful women. Say what you will about such a managerial strategy, but it’s doubtful that the raging sonic beast that is “Sister Ray” would have been unleashed upon an unsuspecting public had someone else taken the helm.

The Velvet Underground White Light White Heat (1968) Debate rages over Wilson’s level of involvement with the first Velvet Underground record. Though Andy Warhol was given full credit for production duties (most likely for financial reasons,) Wilson is said to have produced at least four of its tracks and to have supervised the final mix-down of the whole thing. Whatever the case, he was brought back as full-on producer for this sophomore effort, the most challenging and uncompromising in the band’s catalog. Having worked with the Velvets before, Wilson probably knew it best to leave them to their own devices. Besides, he had other things going on anyway. Guitarist Sterling Morrison once recounted that Wilson, ever the lady’s man, spent most of the studio time entertaining a rotating roster of beautiful women. Say what you will about such a managerial strategy, but it’s doubtful that the raging sonic beast that is “Sister Ray” would have been unleashed upon an unsuspecting public had someone else taken the helm. The Soft Machine The Soft Machine (1968) Recorded while on tour in the states (supporting Jimi Hendrix), The Soft Machine’s debut was one of the first high-profile rock albums to blatantly fuse jazz with psychedelia. From start to finish, this proto-prog opus is a frenetic whirlwind of Robert Wyatt’s evocative vocals and dexterous drumming, Kevin Ayers’ rubbery basswork, and the truly unique emanations of Mike Ratlidge’s distorted Holiday Deluxe organ. The songs transition seamlessly into one another, pausing only at the end of side one, a sequencing practice that would become common in the age of the Concept Album but almost unheard of at this time for any rock band. Wilson’s jazz background was surely an asset to the proceedings. But once again, his personal life seemed to play the true role in the album’s construction. Ayers recalled Wilson being on the phone with one of his girlfriends more often than him giving musical guidance to the band.

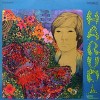

The Soft Machine The Soft Machine (1968) Recorded while on tour in the states (supporting Jimi Hendrix), The Soft Machine’s debut was one of the first high-profile rock albums to blatantly fuse jazz with psychedelia. From start to finish, this proto-prog opus is a frenetic whirlwind of Robert Wyatt’s evocative vocals and dexterous drumming, Kevin Ayers’ rubbery basswork, and the truly unique emanations of Mike Ratlidge’s distorted Holiday Deluxe organ. The songs transition seamlessly into one another, pausing only at the end of side one, a sequencing practice that would become common in the age of the Concept Album but almost unheard of at this time for any rock band. Wilson’s jazz background was surely an asset to the proceedings. But once again, his personal life seemed to play the true role in the album’s construction. Ayers recalled Wilson being on the phone with one of his girlfriends more often than him giving musical guidance to the band. Harumi Harumi (1968) – Harumi was an enigmatic Japanese singer/songwriter, about which little is known today. While briefly based in New York in the late ‘60s, he cut this album. It’s received very little press over the years, and it remains an obscurity even to hardcore psych fans. Why a project like this—a completely unknown singer with a thick Japanese accent performing experimental music (on a double-album no less!)—was green-lighted by a major American record label will remain an even bigger mystery. But without a doubt, only someone like Tom Wilson could have made it happen. Parts of it, particularly the poppier material on the first disc, are brilliant, a lysergic fusion of rock, jazz, and eastern folk. The material on disc 2 can be tedious, particularly the god-awful twenty minute spoken-word piece, “Twice Told Tales of the Pomegranate Forest ”. Still, the album’s relentless risk-taking and experimentalism make it one of the most bizarre records of its era, and considering the producer who was involved here that’s really saying something!

Harumi Harumi (1968) – Harumi was an enigmatic Japanese singer/songwriter, about which little is known today. While briefly based in New York in the late ‘60s, he cut this album. It’s received very little press over the years, and it remains an obscurity even to hardcore psych fans. Why a project like this—a completely unknown singer with a thick Japanese accent performing experimental music (on a double-album no less!)—was green-lighted by a major American record label will remain an even bigger mystery. But without a doubt, only someone like Tom Wilson could have made it happen. Parts of it, particularly the poppier material on the first disc, are brilliant, a lysergic fusion of rock, jazz, and eastern folk. The material on disc 2 can be tedious, particularly the god-awful twenty minute spoken-word piece, “Twice Told Tales of the Pomegranate Forest ”. Still, the album’s relentless risk-taking and experimentalism make it one of the most bizarre records of its era, and considering the producer who was involved here that’s really saying something!