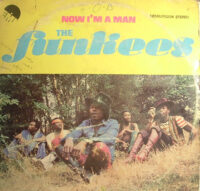

Their name may be slightly cringe, but the Funkees rank as one of the best Nigerian groups from that Western African country’s 1970s musical heyday. Formed by guitarist Harry Mosco at the conclusion of Nigeria’s 1969 civil war, the Funkees initially were a cover band, interpreting songs by artists such as the Beatles, Fela Kuti, Aretha Franklin, Rolling Stones, and Elvis Presley. In 1973, the Funnkees moved to London and used that opportunity to open for popular groups such as Kool & The Gang, Osibisa, and Fatback Band.

The Funkees’ 1974 debut album, Point Of No Return, abounds with gritty Afrobeat cuts animated by Mosco and Jake Sollo’s flinty guitar riffs and the robust polyrhythmic attack by drummer Chyke Madu and percussionist Sonny Akpabio that surely made Fela sweat in approval. (Trivia: Akpabio later played in Eddie Grant’s post-Equals 1980s band.)

With 1976’s Now I’m A Man, the Funkees leaned more heavily into their funk-rock inclinations. You can hear this shift toward a sound more friendly to Western ears with the opening title track. It begins in mellow, Latin shuffle mode, like a blissed-out Santana, but Sollo’s (or Mosco’s) wah-wah guitar squelches increase the funkadelic factor. Mohammed Ahidjo’s warm, proud vocals really draw you in to this self-empowerment jam. I love to open DJ sets with this song, as it instantly conjures positive vibes.

The humid afro-funk trudge of “Korfisa” is sexy as hell while the slinky, self-explanatory “Dance With Me” is the sort of nonchalantly funky entreaty to get on the good foot on which !!! have based a large chunk of their output. “Mimbo” features the sort of sparse, percussion-heavy groove that would segue well into undulant cuts by Konk or Liquid Liquid—a very good thing. With its refrain of “everybody get together,” infectious call-and-response vocals, and fiery guitar/organ interplay, “Salam” is a buoyant, optimistic dance track that rolls and roils with an unstoppable force. This could still work on 2023 dance floors.

“Time” acts as sort of a reprise of “Now I’m A Man,” but with different lyrics and lighter overall feel. The instrumental “303” ventures into prog territory, with its circuitous piano motifs, surprising tempo changes, complex counterpoint between the curlicuing bass and pointillistic guitar calligraphy. It’s the Funkees at their most mind-bendingly virtuosic. The album’s only dud is the unengaging ballad, “Patience.”

In 2016, the Austrian label Presch Media GmbH reissued Now I’m A Man—albeit with no liner notes or any credits whatsoever, which is scandalous. Unfortunately, prices on Discogs for this edition have skyrocketed to as high as $100. Perhaps another reissue done with more care for historical context is in order. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.