The music world suffered a serious loss when Keith LeBlanc, the powerful and influential drummer for Grandmaster Flash & The Furious Five, Mark Stewart And The Maffia, and many others, passed away on April 4 at age 69. The eulogies for his work behind the kit were effusive and widespread. Understandable, as LeBlanc had lent his rhythmic prowess to two major movements in the 1980s, recording several sessions for artists on the pioneering hip-hop label Sugar Hill and for the innovative UK dub imprint On-U Sound.

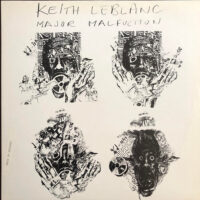

Beyond those important contributions, LeBlanc sat in on studio dates for popular artists such as R.E.M., Tina Turner, and Nine Inch Nails. He also maintained an interesting, uncompromising solo career, marked by the galvanizing 1986 debut LP, Major Malfunction. This followed the 1983 underground-club sensation “No Sell Out,” in which LeBlanc spliced snippets of fiery Malcolm X speeches into a rock-ribbed electro/hip-hop jam.

With On-U boss Adrian Sherwood at the controls for Major Malfunction, LeBlanc led a group featuring fellow Sugar Hill/Tackhead badasses Doug Wimbish (bass, guitar) and Skip McDonald (guitar, keyboards, engineer). (The title refers to the description of the Space Shuttle Challenger exploding shortly after liftoff in early 1986.) Finally free to do their own thing, LeBlanc and crew let loose with a sampladelic banger built more for the concrete bunker than for the dance floor.

“Get This” launches the record with sick keyboard warpage that’s like a virulent bug moving through an intestinal tract. Soon, LeBlanc’s huge beats pound through a disorienting miasma of disturbingly slurred vocals and fried guitar riffs. On the brutal industrial funk of “Major Malfunction,” LeBlanc threads samples of broadcasters, then-President Reagan talking about the tragedy mentioned in the previous paragraph, with bonus commentary from the Beat author William S. Burroughs, e.g., “Your planet has been invaded.” More jagged, pugilistic electro funk caroms forth on “Heaven On Earth.” “There ain’t no heaven on Earth nowhere,” growls an angry Black man amid sampled yells of the damned. Clearly, LeBlanc’s m.o. was to overwhelm the listener with spoken-word samples and equilibrium-subverting production techniques applied to militant, club-wrecking tracks.

Reputedly, “M.O.V.E.” was a Ministry song that LeBlanc repurposed for his own record; Keith had worked on that band’s 1986 LP, Twitch. It’s a rugged, polyrhythmic shuffle on which African Head Charge member Bonjo’s bongos really slap the track into overdrive. The funkiest and most psychedelic cut here, “Technology Works Dub” is laced with eerie chants and distorted whooshes, with a robotic voice intoning, “Technology works. Technology delivers. Technology is a modern quasi religion.” LeBlanc obviously was skewering the blind faith corporations put in tech while simultaneously using sonic gear designed with it to prove its value in other fields. The chaotic piece “You Drummers Listen Good” closes the album strangely, as a gravel-voiced preacher rants about young women falling for drummers, before it eases back into a slab of exotic funk rock.

The stilted quality of Major Malfunction‘s rhythms was endemic to a lot of vanguard electronic music and hip-hop in the ’80s. While working within those technological limitations, though, LeBlanc found a way to make his beats funky and timbrally exciting—they hit with the exaggerated THWACK of fists hitting faces in Hollywood blockbusters. There were good reasons why so many musicians—both experimental and mainstream—wanted him to supply beats. RIP, Keith LeBlanc. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.