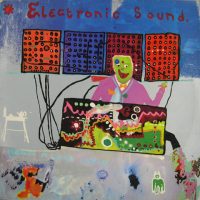

It was only five months ago when I reviewed Taj Mahal Travellers’ August 1974 in this space, and sadly, on October 12, that group’s leader, Takehisa Kosugi, passed away at age 80. So, this seems like an opportune time to review the violinist/composer’s best-known solo work, Catch-Wave.

Consisting of two sidelong tracks, Catch-Wave is not a million kilometers from what Taj Mahal Travellers were doing. To recap: In my review, I wrote, “These Travellers sacralize your mind with an array of string instruments, mystical chants, bell-tree shakes, and Doppler-effected electronics that are as disorienting as they are transcendent.” Here, Kosugi improvises solo on violin and electronics to similar trance-inducing effect.

In the 26-minute “Mano-Dharma ’74,” Kosugi manifests a fantastically desolate and gently fried sound that falls somewhere among rarefied realms of Terry Riley’s “Poppy Nogoods All Night Flight,” Fripp/Eno’s “Swastika Girls,” and Bernard Herrmann’s Psycho soundtrack. The fibrillations and oscillations wax and wane with hallucinogenic force and logic while a steadfast drone woo-whoas in the middle distance. After a while, you begin to think of this track not so much as music as it is the alien babbling of a mysterious organism that’s eluded scientific study. This is very bizarre psychedelic minimalism, and I love it.

“Wave Code #E-1” clocks in at a mere 22 minutes, and features Kosugi’s deep, ominous voicings, in addition to a modulating drone that almost sounds like Tuvan throat-singing. Heard from one angle, it may seem like Kosugi is merely fucking around with the cavern of his thorax, like a child in front of the rotating blades of an air-conditioner. Heard from another angle, though, this piece comes off like the Doppler Effected groans of a woozy and weaving deity hell-bent on scaring the bejesus out of you. Somehow, this cut is even stranger than the very weird A-side… and I love it.

Besides helming Taj Mahal Travellers, Kosugi played in Group Ongaku, was part of the Fluxus movement, and acted as music director for Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 1995-2011. He was one out-there cat, and he created some timeless music, of which Catch-Wave is a prime example. Rest easy, master musician.

[Note: The excellent Superior Viaduct label is reissuing Catch-Wave on Nov. 9] -Buckley Mayfield