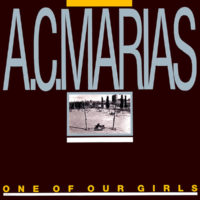

To appreciate 69, the debut album by the UK’s A.R. Kane, you have to shed your rock expectations and simply drift in the alien aura that Alex Ayuli and Rudy Tambala summoned from Buddha knows where. While early singles like “When You’re Sad” and “Lollita” relied on noisy surfeit (critics of the time somewhat accurately described them as “the black Jesus And Mary Chain”), most of 69 is downright spare, yet strangely moving. But does it rock? Not really.

That A.R. Kane subsequently were classified as “shoegaze” is not totally on point, either, although they did have elements of that genre. Actually, the duo were more diverse than their shoegaze contemporaries, delving into dub, Miles Davis’ late-’60s/early-/’70s jazz fusion, acid house, and sampladelic dance music (cf. M|A|R|R|S’ Pump Up The Volume).

As for 69, there’s a watery disorientation to much of it, an exploratory restlessness that recalls Tim Buckley’s Starsailor and Can’s Future Days. (Simon Dupree And The Big Sound/Gentle Giant member Ray Shulman produced and contributed bass; his role in this sonic triumph should not be underestimated.) Singer Ayuli’s voice here is a small, unmoored presence buffeted by breezes and gales of sound. It’s a voice deflated of all tension—a pure embodiment of bliss.

69‘s opening cut, “Crazy Blue,” catches you off-balance right away. A feather-light, quasi-jazz romp embroidered with shimmery halos of guitar, it totally goes against the grain of A.R. Kane’s previous recordings. “Suicide Kiss” starts almost funkily before it quickly dissolves in billows of guitar haze, while still maintaining a semblance of song structure. “Baby Milk Snatcher”—which originally appeared on 1988’s brilliant Up Home! EP—sounds like a meticulously carved masterpiece in the context of 69‘s general amorphousness.

“Dizzy,” “Sulliday,” “Spermwhale Trip Over,” and “The Sun Falls Into The Sea” are unprecedented (from a late-’80s perspective) sketches of souls in various states of exaltation. One must conjure ludicrous metaphors to describe these songs, and honestly, it’s too hot right now for me to do that. Go through moldering issues of British mag Melody Maker for examples.

Ultimately, 69 doesn’t douse me in the icy ecstasy that Up Home! does. However, in its own enigmatic way, 69 is a weird trip worth taking. A.R. Kane’s intentions were baffling, and that’s always a positive, in my book. Every foray they made surprised in rewarding ways. Thirty-six years after its release, 69 is still flummoxing heads and revealing new, fascinating facets. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.