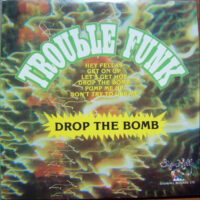

Do you like to party? Trouble Funk can help facilitate that. The Washington, DC ensemble are the standard-bearers of go-go, a strain of chunky, percussion-heavy funk and call-and-response rapped vocals that’s organically geared to activate bodies and stimulate libidos. When you need music that’s even more muscular and obsessively drilled than James Brown’s J.B.s, call on Trouble Funk.

The title track’s an apt entry point for Trouble Funk. “Drop The Bomb”‘s lyrics identify which crews Trouble Funk would like to obliterate with explosives. Now, that’s pretty mean and blunt, but we don’t go to TF for nuanced, insightful verses. You can find more food for thought in any random big city’s graffiti. (If the bombs are metaphors for TF’s songs, I take all of this back.) Rather, we listen to them for grooves that have infinite playback and sweat-inducing potential. And “Drop The Bomb” ranks as one of TF’s most inspirational jams in a catalog loaded with same. Extra credit for the wild synth tomfoolery streaking across the potent polyrhythms and general party sounds.

The album’s other smash, “Pump Me Up,” stands as one of the vaunted Sugar Hill label’s most iconic rap tracks. It’s been sampled at least 160 times (mostly for the amped, stuttered refrain of the title) and is by far their most streamed song on $p0t1fy. “Pump Me Up” leverages maximal funkiness with a killer subliminal bass line, elasticated synth bow bows, whistles, and robust hand-percussion embellishments. Hell, even UK drum & bass maverick Squarepusher lifted the rousing “pumppumppump me up” part for “Fat Controller.” The instrumental breaks must have caused mayhem wherever B-boys/girls gathered… and probably still do.

Beyond these best-known Trouble Funk cuts, the LP has three other crucial tunes. In “Hey Fellas,” call-and-response raps and vocals ping-pong over momentous horn charts, kinetic congas (or are they timbales?), clap-augmented funk beats, and synth bass hot and thicc enough to shatter Funkadelic’s “Flash Light.” It’s a pretty scorching way to start an album that intends to rile up revelers. “Get On Up” is absurdly lit funk for maximal strutting, with satisfying cowbell clonks and some of the hardest-hitting clapper beats and girthy bass purrs outside of a Roger Troutman studio session.

The album’s final track, “Don’t Try To Use Me,” is an ill-advised descent into baby-making balladry. Rare is the funk outfit who can write tolerable slow songs that don’t OD on schmaltz and saccharine. This inexcusable indulgence lasts for over six minutes, but, thankfully, it’s at the record’s end, so it’s easy to skip. This is the only dud on a platter that ranks among the greatest in the pure realm of mood elevation and ass-moving. As Trouble Funk shout, “You gotta shake that thang!” -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.