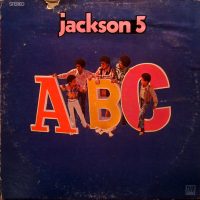

I am asking you to take seriously the second album by the Jackson 5. ABC peaked at #4 in the US albums chart, and it marked a significant advance for the Gary, Indiana song-and-dance boys, led by the irrepressible 11-year-old Michael. Even though “I Want You Back” hit big on the J5 debut LP, this was when it dawned on the world that he was destined for supernatural stardom. (Note: I’m not going to touch on Michael’s post J5 years and all the problematic baggage he accrued until his death in 2009. Rather, I’m going to focus on the abundantly raw and fresh talent of the pre-adolescent Jacko, for the sake of everybody’s mental health. If you want to read an unsparing analysis of Michael’s troubled life, check out Paul Morley’s devastating The Awfully Big Adventure: Michael Jackson In The Afterlife.)

You know the two #1 singles here—“The Love You Save” and the title track— by heart, and yet (if I may project) you still get a rush when you hear them 50-plus years later. They were written by The Corporation, a songwriting/production team headed by Berry Gordy and including Freddie Perren, Deke Richards, and Fonce Mizell, brother of Larry, another formidable songwriter/producer. These ringers were trying to fill the void left by supreme hit-makers Holland/Dozier/Holland, who’d departed from Motown in late 1967.

Whoever decided to start the album with “The Love You Save” deserves respect. The excitement meter slams to 11 from the first second as Michael’s voice cuts through the Funk Brothers’ session-pro bubblegum-funk/soul hullabaloo like a perfectly modulated clarion. The vocal interplay is fantastic; these are the best “woo”s, the best “bum da bum bum”s. It was likely rehearsed for grueling hours under the relentless tutelage of Berry Gordy and papa Joe Jackson. You can hear the prodigies’ voices pinging around the stereo field with quickness and stealth. From that breathless beginning, the LP descends into the lightweight, strings-laden ballad “One More Chance.” It verges on maudlin, but some nice, subtle guitar clangs in the margins. As for “ABC,” anyone who grew up on pop radio in the early ’70s and/or watched the Jackson 5 TV cartoon series can’t help feeling their heart inflate with euphoric helium from the first falsetto “ba ba ba BA BA.” The carefree, spring-legged funk of this pop perfection provides an endlessly renewable source of energy; ask Naughty By Nature and Ghostface Killah. Listening to “ABC,” you don’t even pause to think about how in the hell an 11-year-old from the Midwest’s stinkin’ armpit could know about love and how he could have the gonads to implore a girl to show him what she can do. Counterpoint: Love isn’t as easy as ABC… nor even as XYZ.

Let us now linger on “2-4-6-8,” the album’s underdog champion, written by the Northern soul star Gloria Jones and British songwriter Pam Sawyer, who also penned the Supremes’ “Love Child.” “2-4-6-8” is a lesser-known classic that’s actually more sublime than the two number ones. The guitars, bass, drums, handclaps, and vocal arrangement are all phenomenal; Jermaine steps up righteously when needed and the backing falsettos are on point. The melody and chorus (basically a cheerleader’s chant) should come off as corny, but are utterly inspirational, and the undulating funk rhythm acts as a sonic trampoline. When Michael shouts, “I may be a little fella/but my heart is as big as Texas/I have all the love a man can give/and maybe a little bit extra,” you might die from the cuteness. I once played this song 20 straight times, and I’ll probably do so again. It’s cheaper and more effective than any upper on the market.

After that peak, the highlights somewhat taper off. The Holland/Dozier/Holland tune “(Come Round Here) I’m The One You Need” is a headlong headrush of Motown Northern soul, but kind of boilerplate-y. Co-written by Stevie Wonder, the power ballad “Don’t Know Why I Love You” really pushes Michael to the extreme of his emotional range with regard to the mystery of love. Against the odds, the song convinces you that this little dude actually has experienced romantic turmoil. And how ballsy was it to attempt the heavy, dank funk of Funkadelic “I’ll Bet You”? The song’s actually better suited for the Temptations, but J5 gamely embody its grown-folks funkitude. The guitarist (damn Motown for the lack of credits) goes the fuck off with a fried solo that’s redolent of Dennis Coffey’s crispy tones. The album closes with “The Young Folks,” which the Jacksons’ mentors the Supremes originally did. It’s unintentionally funny to hear MJ trying to inhabit the persona of a spokesman for the young generation. Still, it’s a solid orchestral soul tune with a killer bass line and Michael emotes passionately with jutted jaw.

The prodigious Motown factory was humming along at an astonishing rate in 1970, and J5 certainly benefited from it. But the brothers also showed they could rise to the sky-high standards Gordy & co. demanded from their roster, even though they were too young to vote. I daresay that this is J5’s peak. Now let us know who played on it, Mr. Gordy. -Buckley Mayfield