Ironically enough, Caetano Veloso’s almost entirely English language album is one of the most misunderstood of his classic 60s/70s period amongst English-speaking audiences (first place goes to Araca Azul, but that one at least gives you fair warning of its polarizability by the Caetano-in-bikini cover). Recorded while in exile in London, the album marks a dramatic musical departure from his first 2 solo outings that he would continue to explore up through 1977 or thereabouts. I must confess I don’t know too many details of Caetano’s (or Gilberto Gil’s) exile in London. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity on the part of the British, though there was probably no reason why anyone there should’ve known who he was. Apparently some Traffic members were big fans, and even helped out on Gil’s sessions but if I were George Harrison or Twink or Jimmy Page or Bill Wyman or Jack Bruce or Marc Bolan or Mike Heron and someone told me that the leading light of Brazil’s new underground rock movement was in my midst, I would totally be over there asking if he wanted to go bowling or split an appetizer or something. Or if I was Jimmy Page, I would ask if I could steal his guitar line from “Irene”.

Ironically enough, Caetano Veloso’s almost entirely English language album is one of the most misunderstood of his classic 60s/70s period amongst English-speaking audiences (first place goes to Araca Azul, but that one at least gives you fair warning of its polarizability by the Caetano-in-bikini cover). Recorded while in exile in London, the album marks a dramatic musical departure from his first 2 solo outings that he would continue to explore up through 1977 or thereabouts. I must confess I don’t know too many details of Caetano’s (or Gilberto Gil’s) exile in London. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity on the part of the British, though there was probably no reason why anyone there should’ve known who he was. Apparently some Traffic members were big fans, and even helped out on Gil’s sessions but if I were George Harrison or Twink or Jimmy Page or Bill Wyman or Jack Bruce or Marc Bolan or Mike Heron and someone told me that the leading light of Brazil’s new underground rock movement was in my midst, I would totally be over there asking if he wanted to go bowling or split an appetizer or something. Or if I was Jimmy Page, I would ask if I could steal his guitar line from “Irene”.

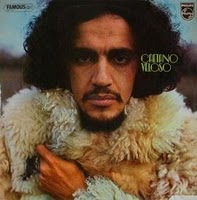

One aspect of Veloso’s exile period is quite : he did NOT like it. The cover is amazing. Caetano looks like he’s 50, he’s cold, and you just told him a mildly offensive joke. One would assume this album is as bleak as Pink Moon but the first couple of songs might surprise you. “A Little More Blue” opens with a laidback, meandering acoustic figure that sounds a bit mellow but certainly not conducive to soul-bearing. The lyrics are about events that have made him sad, even though at the present moment “I feel a little more blue than then”. Along the way he peppers in references to his own exile and some truly vivid lyrics (“her dead mouth with red lipstick smiled”). An odd, dichotomous opener. “London, London” is for me the standout. And, oddly enough, it’s the jauntiest track, replete with playful flute like Donovan’s 67-era acoustic sides. It’s one of the most exquisitely beautiful songs I’ve ever heard concerning alienation, loneliness, and, above all, homesickness. In this respect, it can be seen as the post-traumatic counterpart to the desperate “Lost in the Paradise” from his previous album. And while I hold that song to be one of the best songs ever written, period, “London, London” offers the beautifully resigned flipside of that coin. And all this from a song whose refrain is “My eyes go looking for flying saucers in the skies”. Things start to get a bit darker with the more-produced “Maria Bethania”, a plea to his sister. “If You Hold a Stone” is an expanded, highly repetitve reworking of “Marinheiro So” from the previous album. I’m not going to pretend to know what he’s talking about here (even though it’s in English and he repeats it like 30 times) but I could listen to it all day long. The last song “Asa Branca” is the only Portuguese-language track on the album and as such it’s an emotionally powerful return to relatively familiar territory for Caetano. The song, written by Luiz Gonzaga and Humberto Teixeira, is about a native farmer (presumably) of Northeastern Brazil having to leave the land and his wife during one of the droughts that often occur in that part of the country because he is unable to make a living. At the end he promises to return. Amazingly, if you really try to live inside this album, you don’t really need to know Portugese to understand what this song is saying. A haunting, ethereal way to end perhaps the most personal album in Veloso’s storied career.

This album is notable for several reason. Firstly, it marks a dramatic change in musical direction for Veloso. I’ve never heard an album with a greater sense of space. There is a lot of silence on this album and it itself is utilized almost as an additional instrument, a “symphony of silence” (mental copyright) if you will. His first solo album was lush and sprightly and full of subtle sonic experimentation. His second album made the sonic experimentation much more explicit and combined this with a panoramic feeling that made that album at times feel tense and murky (not a bad thing in this case). This album does a dramatic about-face with its spare, acoustic lines, occasional bass-and-drum backing, and lyric-centric approach. This formula would reach full fruition on Transa and continue up until 1977’s African-influenced Bicho. The second notable aspect of this album is how well Veloso’s poetry translates into English. That’s no mean feat. Gil’s more awkward English makes his equivalent album difficult to decipher emotionally but Caetano’s only slightly accented English is perfectly suited to his prose that, though economical, are undeniably evocative and effective at relating emotional depth. Certainly not a place to start for Caetano Veloso, but you should try to find yourself here if you are willing to acquire more than 3 of his albums. –Mike