Like a lot of early 70’s fusion, this is highly indebted to Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew-era work, combining elements of funk, jazz, and avant-garde with Herbie’s own love of electronic keyboards and primitive synthesizers, low on melodic content but high on atmosphere. His work would get progressively funkier as the years went on, but Mwandishi’s three lengthy tracks are concerned more with creating an otherworldy vibe aimed at your head more than your feet. “Ostinato” emerges out of a spacey haze and rides a funky bass riff for much of its duration, a vehicle for a lengthy electric piano solo and propelled by some exotic percussion. A mellow, sleepy backdrop with washes of echoed electric piano and trumpet flourishes carries “You Know When You’ll Get There,” maintaining a quiet mood, though the band occasionally comes together to play a brief melodic figure, while “Wandering Spirit Song” tempers a similar vibe with frequent bursts of free-form noise. Mwandishi comes recommended to anyone with a love of fusion in the days before it largely morphed into a funk/rock showcase for virtuoso soloing. –Ben

Like a lot of early 70’s fusion, this is highly indebted to Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew-era work, combining elements of funk, jazz, and avant-garde with Herbie’s own love of electronic keyboards and primitive synthesizers, low on melodic content but high on atmosphere. His work would get progressively funkier as the years went on, but Mwandishi’s three lengthy tracks are concerned more with creating an otherworldy vibe aimed at your head more than your feet. “Ostinato” emerges out of a spacey haze and rides a funky bass riff for much of its duration, a vehicle for a lengthy electric piano solo and propelled by some exotic percussion. A mellow, sleepy backdrop with washes of echoed electric piano and trumpet flourishes carries “You Know When You’ll Get There,” maintaining a quiet mood, though the band occasionally comes together to play a brief melodic figure, while “Wandering Spirit Song” tempers a similar vibe with frequent bursts of free-form noise. Mwandishi comes recommended to anyone with a love of fusion in the days before it largely morphed into a funk/rock showcase for virtuoso soloing. –Ben

Jazz

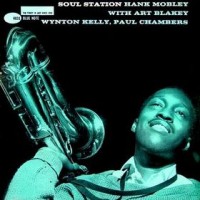

Hank Mobley “Soul Station” (1960)

Hank Mobley recorded this album fresh out of jail after being convicted for heroin posession. Maybe it was relief at finally being free, but the playing here is beautifully relaxed and poised, with a strong sense of flow. As a player, Mobley was sometimes ill-served by recording engineers, but he sounds superb here. And no complaints about the band! There’s nothing revolutionary here, which may lead you to underrate this record; I used to, but the more I get to know it, the better it sounds. —Brad

Keith Jarrett “Death and the Flower” (1974)

In the early 70s, Keith Jarrett formed two groups. One recorded for the German label, ECM, the other (as on this LP) for the traditional American Jazz label, Impulse. The Impulse team consisted of Paul Motian on drums, Dewey Redman on reeds, Charlie Haden on bass, Guilherme Franco on percussion and Jarrett on the grand piano. I prefer this group to the ECM band. In both bands, Jarrett never touched an electric keyboard. Everybody was into some kind of spiritual calling at that time; Jarrett is no exception as the album title and his “poem” on the cover show. Death And The Flower is an example of how Keith Jarrett helped shape the way Jazz was to sound in the future. A new “World Music” feel and the chamber music like intimacy make this an innovative LP. The music still sounds fresh and relevant. The first side of this album, recorded in ’74, is filled with the title track. It spends the first minutes to create an African atmosphere with percussion and flute. Then the double bass contributes a riff and eventually, the piano starts and after a searching phase, the beat carries the song to harmonic sequence of minor chords. As the song flows, each musician takes a chance to show his skills. Then, the song slows down just to pick up a new speed, and Keith provides an irresistible riff on the piano moving the band to a dense groove.

Prayer is a slow and quiet meditation showing how subtly this group plays. It’s amazing to hear how well each musician listens to what is going on. Jarrett’s improvisation demonstrates a strong influence of the classical tradition, notably Debussy, and at one point, he creates a minimalist pattern á la “Steve Reich”. The last song, Great Bird, recalls the Coltrane sound of his last years. Based on the theme (a falling sequence), there’s free collective improvisation. The band corresponds in dreamlike confidence. Death And The Flower, in a word, is recommendable, not just to Jarrett fans. –Yofriend

Pat Metheny & Ornette Coleman “Song X” (1986)

I love unlikely combinations in musical settings. I also love risks and artists who refuse to be pigeonholed. Nothing is more evident of this than on this improv workout from 1986: guitarist Pat Metheny and the innovative saxophonist/free jazz veteran Ornette Coleman’s Song X. Backed by two other Jazz legends, drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Charlie Haden, along with Coleman’s son, Denardo on Percussion, comes a free jazz gem that seemed to come from nowhere. Metheny shocked all of his defectors who loathe his smooth jazz tendencies on this record. At the time Song X was released, he was enjoying massive success with The Pat Metheny Group, filling venues and gaining extensive airplay with their highly accessible brand of fusion. Then comes this curve ball. He had always had an outspoken admiration for Ornette Coleman but the combination of the two in a musical setting still was a bit bizarre – but effective.

The interplay between Metheny and Coleman is unbelievably natural with Metheny playing abstract guitar lines perfectly intertwined with Coleman’s angular alto. Jack DeJohnette’s frantic (but cohesive) drumming is in fine form, he manages to squeeze everything out of his kit on this record, and then some. Bassist Charlie Haden is no stranger to this idiom (he’s been playing alongside Coleman since the late fifties) and sits in perfectly, providing a pulse all his own. Coleman’s son Denardo adds some esoteric percussion textures as well. It even stays innovative and fresh when Metheny picks up his dreaded guitar synth on one track. Song X isn’t just another set by a jazz super group, this record manages to do what all classic free jazz records have done before and after: be accessible, yet challenging, without being contrived. There is nothing trivial about this record. It’s a swinging set of avant-garde goodness by some of the best (and one with some new found street-cred) in the business. These guys dug playing on this session and you can feel the inspiration in the music. –ECM Tim

Quiet Chaos:

An Introduction to ECM Records

ECM Records is a jazz label founded in 1969 in Munich, Germany by producer/bassist Manfred Eicher. ECM (Edition of Contemporary Music) became known as a label that created a musical environment all its own. The recordings were sparse, minimalistic and relying on space as an accent to create what is now widely known as the “ECM sound”. Most of the recordings were rooted in jazz but combined with other genres. As well as blues, funk and rock, various forms of European folk, world music and contemporary classical music frequently found its way into the landscape. From the packaging, to the pristine production style, Eicher’s releases all are linked with a certain aesthetic that ties them together; he has definitely had a vision in mind. One reviewer from Coda Magazine described the music as “The most Beautiful Sound Next to Silence.” But not all critics shared the same opinion.

The music was, and still is, ostracized for being self-absorbed, cold, and lacking soul. Depending on the listeners taste, the label has also been credited (or accused) of ushering in the New Age era. A number of releases do indeed have these qualities that can drag down and can get a bit arid. But there are many recordings that hit the mark, where space fills the gaps and silence gains a voice, resulting in exciting and innovative art.

Manfred Eicher’s ECM has had a significant impact on the evolution of jazz and improvised music and how it is produced, performed and recorded. By using subtlety as a tool, and combining different styles, his musical stamp has managed to produce some exploratory, modern sounds that could easily suit a broad range of musical tastes. The label is still active and going strong today and Eicher is still applying his “less is more” approach to dozens of recordings each year.

Listed here are some releases that will hopefully dispel some of the negativity surrounding the label:

1. Gateway Gateway (1975) Guitar trio set featuring John Abercrombie on guitar, the great Jack DeJohnette behind the drums, and Dave Holland on bass. This record covers everything from post-bop swing to abstract, sonic explorations. This is a criminally underrated guitar trio record, if not one of the best releases from ECM.

1. Gateway Gateway (1975) Guitar trio set featuring John Abercrombie on guitar, the great Jack DeJohnette behind the drums, and Dave Holland on bass. This record covers everything from post-bop swing to abstract, sonic explorations. This is a criminally underrated guitar trio record, if not one of the best releases from ECM.

2. Chick Corea , Dave Holland, Barry Altschul ARC (1971) Chick Corea on piano with Dave Holland on bass and Barry Altschul on percussion – Any fans of the classic piano trio should study this record, both lyrical and dissonant; it bridges the gap between free improv and structure.

2. Chick Corea , Dave Holland, Barry Altschul ARC (1971) Chick Corea on piano with Dave Holland on bass and Barry Altschul on percussion – Any fans of the classic piano trio should study this record, both lyrical and dissonant; it bridges the gap between free improv and structure.

3. Julian Priester Love, Love (1973) An “electrocoustic” jazz/ funk session with tight horn arrangements, wah guitars, low-fi bass lines and eerie synth swells mingled with Latin flavored piano runs. This is a modern sounding, progressive record that still sounds fresh today-a Jive Time favorite.

3. Julian Priester Love, Love (1973) An “electrocoustic” jazz/ funk session with tight horn arrangements, wah guitars, low-fi bass lines and eerie synth swells mingled with Latin flavored piano runs. This is a modern sounding, progressive record that still sounds fresh today-a Jive Time favorite.

4. Nils Petter Molvær Solid Ether (2000) This is trumpet player Nils Petter Molvær’s second release by this project ; a stew of trumpet swirls, loops, guitars, and various electronics with programmed beats intertwined with live drums, along with gentle female vocal interludes. There’s also some sampling from DJ Strangefruit .

4. Nils Petter Molvær Solid Ether (2000) This is trumpet player Nils Petter Molvær’s second release by this project ; a stew of trumpet swirls, loops, guitars, and various electronics with programmed beats intertwined with live drums, along with gentle female vocal interludes. There’s also some sampling from DJ Strangefruit .

5. John Abercrombie Timeless (1975) Another trio record featuring John Abercrombie and Jack DeJohnette, only this time Jan Hammer on keyboards joins the fold. I had to include this spaced out fusion masterpiece. Frenetic drumming and fuzzed out guitar and organ washes create psychedelic soundscapes with funky breaks alongside tender acoustic guitar/piano duets. No Miami Vice theme here.

5. John Abercrombie Timeless (1975) Another trio record featuring John Abercrombie and Jack DeJohnette, only this time Jan Hammer on keyboards joins the fold. I had to include this spaced out fusion masterpiece. Frenetic drumming and fuzzed out guitar and organ washes create psychedelic soundscapes with funky breaks alongside tender acoustic guitar/piano duets. No Miami Vice theme here.

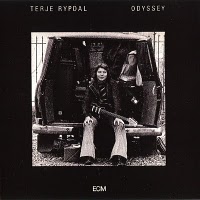

For further listening check out Ebhard Weber’s Colours of Chloë (1973); think Tortoise, Talk Talk and Him (not to be confused with the metal group of the same name). Fans of progressive rock and fusion such as early King Crimson and Miles Davis’ In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew should give guitarist Terje Rypdal’s first four ECM records a spin: Terje Rypdal (1971), What Comes After (1973), Whenever I seem to be Far Away (1974) and Odyssey (1975). More recent releases include Fender Rhodes/pianist Nik Bärtch’s quartet Ronin (2006) that focuses on groove and repetitive motifs creating tension as the music evolves. Drummer Thomas StrØnen and Saxophonist Ian Ballamy’s group Food’s Quiet Inlet (2010) craft a starkly beautiful, atmospheric blend of electronic and acoustic sounds, if you like live electronics and down tempo check this out. – ECM Tim

Are we forgetting your favorite ECM recording? We’d love to hear your comments:

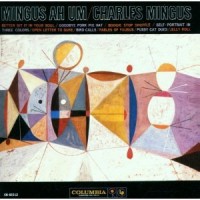

Charles Mingus “Mingus Ah Um” (1959)

Mingus Ah Um is almost absurdly energetic. The pure joy of “Better Git It in Your Soul” is some of the most exciting, exuberant jazz I’ve ever heard, with the gospel shouts and calls, and the monumental tempo. Ah Um reminds me of Raymond Scott, as this outpouring of manic sound that seems perpetually on the brink of chaos, but always tightly controlled. I feel like I lack the lexicon to write about jazz, but I know this is some invigorating, essential music that never flags and serves as an excellent riposte to anyone who has the temerity to say that jazz is boring and/or wanky. I do prefer the first side to the calmer second side (or the back half of the album, anyway I don’t own the LP), but it’s all pretty stunning. –Jared

Miles Davis “Get Up With It” (1970)

Without a doubt, one of the greatest albums of them all, a double set only comparable to the likes of the Stooges’ “Funhouse” in its darkness, intensity and raw, funky sexuality. Now for starters let’s get something straight: I loathe “fusion”, and to even CONSIDER putting Miles’ music of the ’70s in that category – a genre filled with lilly-livered chumps like Return To Forever and the Yellow Jackets – is a great disservice to Miles and his music. From 1969 to ’75, Mr. Davis pioneered and created his own unique sounds, a mixture of hard funk, psychedelic rock, avant-garde electronics and free jazz, that has never been equalled in regards to its sonics or its “vibe”. There is NOTHING that can touch the raised-middle-finger jab in the guts felt when one puts on discs like “Dark Magus”, “Live Evil”, “Agharta”, “Big Fun” or “On The Corner”. The feelings of utter loathing and despair, the overwhelming EMOTION of these discs can be too much, yet nothing can prepare you for 1974’s “Get Up With It”, a disc of such wildness and total lack of any commercial forethought (and thank the heavens for that) that it was granted pretty much instant deletion upon release and has mainly only been available from Japan for the last 25 years.

Without a doubt, one of the greatest albums of them all, a double set only comparable to the likes of the Stooges’ “Funhouse” in its darkness, intensity and raw, funky sexuality. Now for starters let’s get something straight: I loathe “fusion”, and to even CONSIDER putting Miles’ music of the ’70s in that category – a genre filled with lilly-livered chumps like Return To Forever and the Yellow Jackets – is a great disservice to Miles and his music. From 1969 to ’75, Mr. Davis pioneered and created his own unique sounds, a mixture of hard funk, psychedelic rock, avant-garde electronics and free jazz, that has never been equalled in regards to its sonics or its “vibe”. There is NOTHING that can touch the raised-middle-finger jab in the guts felt when one puts on discs like “Dark Magus”, “Live Evil”, “Agharta”, “Big Fun” or “On The Corner”. The feelings of utter loathing and despair, the overwhelming EMOTION of these discs can be too much, yet nothing can prepare you for 1974’s “Get Up With It”, a disc of such wildness and total lack of any commercial forethought (and thank the heavens for that) that it was granted pretty much instant deletion upon release and has mainly only been available from Japan for the last 25 years.

Start with the cover: a big, slightly unflattering, grainy photo of The Man. It’s the sight of a man against the world, battling for his own identity. Hit the first track, “He Loved Him Madly” (a tribute to Duke Ellington), a 32-minute ambient piece only broken up occasionally by Peter Cosey’s mumbling guitar lines. It’s one of the saddest damn songs you’ll ever hear, and you can bet yer booty that if it was made by a bunch of white guys in Berlin ca. ’71, every Krautrock freak in town would be hailing it as a classic. Next track “Maiysha” is a schizophrenic one. For ten minutes in merely putters along like a lite Latin number, interrupted sporadically by Miles’ Sun Ra-like organ, then it stops, gets into a hard groove and proceeds to move along to Peter Cosey’s awesome guitar screeches for another five minutes. Hot. “Honky Tonk” is up next, a brief interlude of stop-start rhythms and noisy organ crunch. It prepares you for the next track the unstoppable “Rated X”, THE peak of Miles’ – or maybe anyone’s – sonic capabilities. Part hyperdive breakbeat rhthyms, part uber-funk, and nine parts pure noise, there is no other sound on earth as MOVING as this song. Get up with it. Disc two starts with “Calypso Frelimo”, another 32-minute piece that starts where “Rated X” finishes off. Ecstatic peaks of dark psychedelic jamming, aided by Miles’ wah-wah’d trumpet, gel and compete. “Red China Blues” is a brief number that kicks it in a Chess-Records-meets-Ornette way, and the 15-minute+ “Mtume” once again takes you for a ride with its collision of Cosey’s guitar (a highly under-rated player in a field with the likes of Sonny Sharrock) and about half a dozen percussionists. Finishing is “Billy Preston”, more chilling mid-range avant-funk to close the set. “Get Up With It” is the perfect summation of what was filling Miles’ head at the time: the avant electronics of Stockhausen, the cyclical funk of James Brown, the wailing psych guitar of Hendrix, the improvised freeness of Ornette Coleman and as The Man himself put it, “a deep African thing”. Many words have been written on Miles’ music of this period, but to really GET it, you have to LISTEN to it. Not a word is spoken on GUWI, yet it speaks volumes on its creator’s alienation and sense of despair. As far as so-called “out-rock” goes, this is about as “out” as you could get, and certainly about as purely “psychedelic” as music has ever gotten, so do the done thing and get with it. –Dave

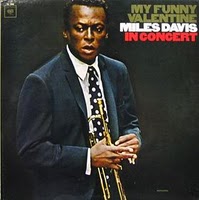

Miles Davis “My Funny Valentine” (1965)

Never has there been such a perfect example of the difference between what we might call the Apollonian and Dionysian (if we were utterly pretentious). In February 1964, Miles Davis and his then band — Tony Williams on drums, Ron Carter on bass, Herbie Hancock on piano and George Coleman on sax — played a concert at New York’s Philharmonic Hall that was subsequently split for release on two LPs. The fast numbers went on Four and More, a fun little album but no great shakes; there’s plenty of power, but not much else. The ballads, though, wound up here, and the end result is one of the most beautiful and moving jazz records I own. It’s stunningly delicate; the five musicians play with almost ESP-like sensitivity to each other. Listen, though, to Miles; he has rarely played with such lyricism, such emotion. “Stella by Starlight” in particular sounds like a direct connection to a place far deeper than any he has gone before. Naked, and necessary. –Brad

Never has there been such a perfect example of the difference between what we might call the Apollonian and Dionysian (if we were utterly pretentious). In February 1964, Miles Davis and his then band — Tony Williams on drums, Ron Carter on bass, Herbie Hancock on piano and George Coleman on sax — played a concert at New York’s Philharmonic Hall that was subsequently split for release on two LPs. The fast numbers went on Four and More, a fun little album but no great shakes; there’s plenty of power, but not much else. The ballads, though, wound up here, and the end result is one of the most beautiful and moving jazz records I own. It’s stunningly delicate; the five musicians play with almost ESP-like sensitivity to each other. Listen, though, to Miles; he has rarely played with such lyricism, such emotion. “Stella by Starlight” in particular sounds like a direct connection to a place far deeper than any he has gone before. Naked, and necessary. –Brad

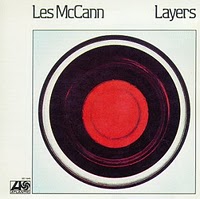

Les McCann “Layers” (1974)

Think of the work of the following artists in the early seventies: Tonto’s Expanding Head Band, The Mizell Brothers, Lonnie Liston Smith, Stevie Wonder, George Duke, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis. If you like their work, you’ll like – love – this album. Aside from an electric bass and three percussionists, this is the epitome of a keyboard album. By overdubbing (this was the first album recorded in 32-track format), McCann employs ARP synths, clavinet, Fender-Rhodes e-piano, and piano to simulate horns, woodwinds, and whatnot. On the basis of funky grooves, he creates a reflective atmosphere that’s both nostalgic and futuristic. The album is structured like a suite, with the tunes fading into each other. The result is something that could be called Prog-Jazz. McCann created a visionary sound when he recorded this album in ’72. Layers is a groundbreaking Fusion album from the early seventies when fusion was not yet something to be ashamed of. The record belongs to the best of that genre. –Yofriend

Think of the work of the following artists in the early seventies: Tonto’s Expanding Head Band, The Mizell Brothers, Lonnie Liston Smith, Stevie Wonder, George Duke, Herbie Hancock, Miles Davis. If you like their work, you’ll like – love – this album. Aside from an electric bass and three percussionists, this is the epitome of a keyboard album. By overdubbing (this was the first album recorded in 32-track format), McCann employs ARP synths, clavinet, Fender-Rhodes e-piano, and piano to simulate horns, woodwinds, and whatnot. On the basis of funky grooves, he creates a reflective atmosphere that’s both nostalgic and futuristic. The album is structured like a suite, with the tunes fading into each other. The result is something that could be called Prog-Jazz. McCann created a visionary sound when he recorded this album in ’72. Layers is a groundbreaking Fusion album from the early seventies when fusion was not yet something to be ashamed of. The record belongs to the best of that genre. –Yofriend

Charlie Parker & Dizzy Gillespie “Bird and Diz”

This is hardly a typical recording, but I have to say that this is my favorite jazz album ever recorded. It’s the only recording to have Thelonious Monk playing together with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, which in itself is pretty amazing. Although their styles are so distinct, they do play quite well together. Hearing them playing together is almost surreal. It’s hard for me to describe how and why I like this album. I think the main reason that I like it is that it’s so strange and so normal at the same time. The tunes exemplify this…two catchy blues (Bloomdido and Mohawk), a laid-back song to the same chord changes as “Stompin at the Savoy” (Relaxin’ with Lee), a slowish and rather bizarre rhythm-changes tune (An Oscar for Treadwell), leap frog which is just ridiculously fast, and rather cheerful…and then…my melancholy baby. And of course…bizarre stuff happens to the harmonies and rhythms when you put these musicians together. One moment it sounds so old-fashioned, the next moment totally modern. I love it all the way! –Alex

This is hardly a typical recording, but I have to say that this is my favorite jazz album ever recorded. It’s the only recording to have Thelonious Monk playing together with Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, which in itself is pretty amazing. Although their styles are so distinct, they do play quite well together. Hearing them playing together is almost surreal. It’s hard for me to describe how and why I like this album. I think the main reason that I like it is that it’s so strange and so normal at the same time. The tunes exemplify this…two catchy blues (Bloomdido and Mohawk), a laid-back song to the same chord changes as “Stompin at the Savoy” (Relaxin’ with Lee), a slowish and rather bizarre rhythm-changes tune (An Oscar for Treadwell), leap frog which is just ridiculously fast, and rather cheerful…and then…my melancholy baby. And of course…bizarre stuff happens to the harmonies and rhythms when you put these musicians together. One moment it sounds so old-fashioned, the next moment totally modern. I love it all the way! –Alex

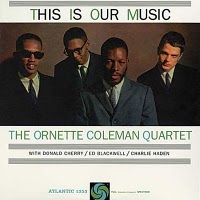

Ornette Coleman “This Is Our Music” (1961)

It was over 30 years ago that I bought my first Ornette Coleman album, Free Jazz, from the second-hand record shop: it was love at first sight (first hear?). Love is inexplicable, at least to those in love, but the sound of Coleman’s alto had an immediate effect on me, an emotional connection, that continues until today. It is the early Atlantic recordings that remain at the heart of my love for Coleman. I have only been listening to This Is Our Music for the past couple of months (I feel no need to rush a love affair), but, other than Free jazz, it has become my favorite of the Coleman-Atlantic albums (but I don’t feel I have to be bound by that judgement in the future). I have heard it said that compared to other figures of the 1960s jazz avant garde Coleman now seems very tame: I think that is true, at least as far as he doesn’t howl and shout in way that threatened to blow away all our assumptions of what music should be, but then the other avant garde sax players tended to fall in behind Coltrane, in their stance of difference they tended to sound the same, while Coleman remains unique. He has created his own musical world, one I find as vivid and friendly as an Impressionist painting, and it is a world that has no successful copies. The one musician who shared this vision was Don Cherry and he is the Engels to Coleman’s Marx, the Watson to his Holmes, the Robin to his Batman – he is the lesser figure, the one who takes his imaginative world from his dominating companion, but maybe he brings Coleman closer, creating a bridge between him and us. Charlie Haden is the anchor for this music, for most of this album playing an idiosyncratic hard bop bass, it has the lines that stabilize the music. The exception is Beauty Is a Strange Thing where, playing with a bow, he allows the music to drift away like a cloud without any edges. Ed Blackwell is a unique drummer (and I much prefer him to Billy Higgins’ work on the earlier Atlantic-Coleman albums) – he is the gentlest of drummers, not giving the music the rhythmic propulsion we expect a drummer to provide, but rather a rhythmic voice responding to and answering the horns. Writing about other Coleman-Atlantic albums I have said that their great limitation is that all the tracks tend to be a bit the same – here there are two numbers that stand out for their difference: the slow and hovering Beauty Is a Rare Thing and the reinvention of Embraceable You. The latter is the only Ornette Coleman version of a standard I know – it is as though Gershwin’s melody has been replanted in a totally alien soil and it has grown in an unforeseeable way, still recognisably having the same shape, but also disturbingly different. –Nick

It was over 30 years ago that I bought my first Ornette Coleman album, Free Jazz, from the second-hand record shop: it was love at first sight (first hear?). Love is inexplicable, at least to those in love, but the sound of Coleman’s alto had an immediate effect on me, an emotional connection, that continues until today. It is the early Atlantic recordings that remain at the heart of my love for Coleman. I have only been listening to This Is Our Music for the past couple of months (I feel no need to rush a love affair), but, other than Free jazz, it has become my favorite of the Coleman-Atlantic albums (but I don’t feel I have to be bound by that judgement in the future). I have heard it said that compared to other figures of the 1960s jazz avant garde Coleman now seems very tame: I think that is true, at least as far as he doesn’t howl and shout in way that threatened to blow away all our assumptions of what music should be, but then the other avant garde sax players tended to fall in behind Coltrane, in their stance of difference they tended to sound the same, while Coleman remains unique. He has created his own musical world, one I find as vivid and friendly as an Impressionist painting, and it is a world that has no successful copies. The one musician who shared this vision was Don Cherry and he is the Engels to Coleman’s Marx, the Watson to his Holmes, the Robin to his Batman – he is the lesser figure, the one who takes his imaginative world from his dominating companion, but maybe he brings Coleman closer, creating a bridge between him and us. Charlie Haden is the anchor for this music, for most of this album playing an idiosyncratic hard bop bass, it has the lines that stabilize the music. The exception is Beauty Is a Strange Thing where, playing with a bow, he allows the music to drift away like a cloud without any edges. Ed Blackwell is a unique drummer (and I much prefer him to Billy Higgins’ work on the earlier Atlantic-Coleman albums) – he is the gentlest of drummers, not giving the music the rhythmic propulsion we expect a drummer to provide, but rather a rhythmic voice responding to and answering the horns. Writing about other Coleman-Atlantic albums I have said that their great limitation is that all the tracks tend to be a bit the same – here there are two numbers that stand out for their difference: the slow and hovering Beauty Is a Rare Thing and the reinvention of Embraceable You. The latter is the only Ornette Coleman version of a standard I know – it is as though Gershwin’s melody has been replanted in a totally alien soil and it has grown in an unforeseeable way, still recognisably having the same shape, but also disturbingly different. –Nick

Terje Rypdal “Odyssey” (1975)

Producer Manfred Eicher’s ECM label has been a mixed bag over the years. Much of the output has been criticized for being homogenized, self-indulgent & dull as well as being praised for genius production, adventurous artists making groundbreaking recordings, with an inner fire underneath the slick recordings. Love it or hate it, there is a definite sound environment that Eicher has created, it’s simply known as the “ECM sound”. The use of space in music, as loud as silence, free improv without a million notes, composed chaos that whispers screams. When it works it is timeless & innovative, when it doesn’t, it can sound like elevator music that was thrown aside because it sounded too much like, well, elevator music.

Producer Manfred Eicher’s ECM label has been a mixed bag over the years. Much of the output has been criticized for being homogenized, self-indulgent & dull as well as being praised for genius production, adventurous artists making groundbreaking recordings, with an inner fire underneath the slick recordings. Love it or hate it, there is a definite sound environment that Eicher has created, it’s simply known as the “ECM sound”. The use of space in music, as loud as silence, free improv without a million notes, composed chaos that whispers screams. When it works it is timeless & innovative, when it doesn’t, it can sound like elevator music that was thrown aside because it sounded too much like, well, elevator music.

Odyssey is guitarist Terje Rypdal’s fourth record for ECM & it works. A double album of low-fi fusion intertwined with progressive rock string interludes, distorted organs, hissy snare fills, groovy bass lines , ethereal horns, & of course, Rypdal’s guitar playing, which sounds like a cross between Jimi Hendrix & an avant garde cello player. The melodies are dark, cold & funky as hell. Rypdal was definitely channeling Miles Davis’ “Bitches Brew” on this record but only softer, all the groove & dissonance, but less crowded, like someone whispering a hurricane in your ear. The record opens with “Darkness Falls”. Rypdal’s guitar screeching like an injured space bird along side organ stabs & chattering drums with the bass searching for a cohesive rhythm: a gentle panic within the group forms but slowly subsides as the sound fades & flows right into the second track, “Midnite”. Warm, pulsating bass & drums lock into each other & they begin to groove with Rypdal’s wah pedal over the top of moaning trombones & snaky organ lines in the background, holding it all together; quietly. Odyssey has it’s heavier moments as well- “Rolling Stone” a twenty-five minute rock-funk gem that sounds as if Sly Stone & crew ran into the boys from Black Sabbath & said, “Let’s jam”. “Over Birkerot” would be perfectly comfortable on a mid- seventies King Crimson record. It does bog down a bit with a couple of almost contemporary classical string/synthesizer drone marathons that can get a little sleepy, but there’s just enough smolder in there to keep the listener curious. The tracks heard on Odyssey still sound relevant. Manfred Eicher’s production stamp make these tunes sound as if they could be on any modern down-tempo electronic record from today. –ECM Tim