Ah, what it must have been like to hear this in 1979. Avant garde pop with funk basslines and frenzied start-stop percussive overtones; a chanteuse that is menacing as often as she is playful (no wonder she was heralded by Patti Smith), this was one of the best first listens I’ve had of an album as of late.

It was recorded over a mere week and a half and consequentially, sounds compact, tense and nervous. There are no lyrical themes whatsoever – the wonderfully odd “Jim on the move” just consists of Lizzy mumbling the title over and over again, the morbid ‘Tumour’ accentuates Lizzy’s love for the minimal and experimental, one that’s exemplified in her later work – the more colourful, worldbeat influenced Mambo Nassau. Also present is the immaculate ‘Mission Impossible’ theme, and a stunning reworking of Arthur Brown’s “Fire” that should throw any preconceived notions of no-wave you have right out of the window.

Don’t get me wrong, the sound of the record is rooted in no-wave, but this defies categorization for the most part; it combines Lizzy’s art-funk leanings and combines it with a cinematic punk aesthetic that ends up being entirely her own. And no, this is not a a covers record – Lizzy’s own songs (most notably the club flavoured ‘Wawa’, the bass propelled “Aya Mood” and the infectious groove of ‘Torso Corso’) hold their own with anything else on the album.

All in all, this is one of the finest albums of the late 70’s NY underground scene. It is pop music striving to be progressive and radical; and succeeding. I was completely enamoured on the first few listens and only expect this to get better with time. Should appeal to all fans of Talking Heads, Blondie and ESG, though Lizzy sounds very little like any of them. —Rashed

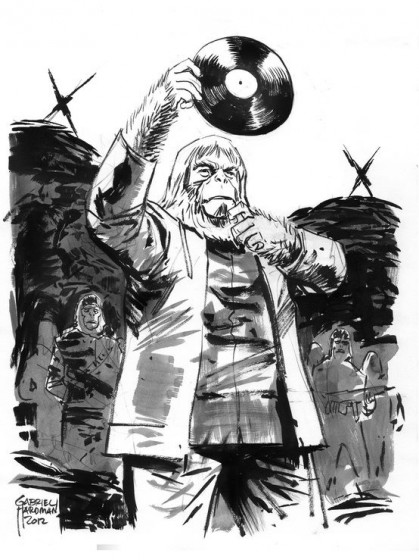

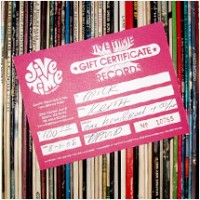

Win the hearts of your favorite vinyl junkie with a Jive Time gift certificate. Our certificates are available in any amount and available to purchase in our store,

Win the hearts of your favorite vinyl junkie with a Jive Time gift certificate. Our certificates are available in any amount and available to purchase in our store,