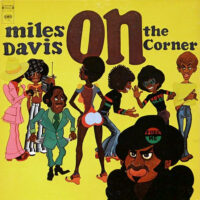

We recently lost the phenomenal jazz-fusion drummer Jack DeJohnette, and tribute must be paid. The man released many great solo LPs, engaged in countless interesting collabs, and sat in on many crucial sessions, but there may be no better way to honor him than to review Miles Davis’ On The Corner. It’s Miles’ peak and, by the way, my second favorite album of all time. (Rest assured, I will likely review one of Jack’s solo or group records in the near future.)

DeJohnette was one of three drummers playing on these sessions (all of which have been collected in a lavish, essential six-CD box set), including Billy Hart and Don Alias. Jack and his cohorts behind the kit—along with an array of percussionists, featuring tabla master Badal Roy and conga supremo Mtume—helped to make On The Corner a tornado of innovative rhythm. But it’s so much more than that, as well.

With On The Corner, Davis strove to appeal to the young Black Americans who dug Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, and Sly & the Family Stone. Yeah, that didn’t pan out. Insult to injury, the establishment jazz critics couldn’t handle it, either. They were vexed by one of the most rhythmically complex, atmospherically ominous, and brutally psychedelic works ever to get classified as “jazz.” In hindsight, you have to wonder how they blew it so badly.

The funny thing is, Davis was in the midst of a heavy Karlheinz Stockhausen phase before heading up the On The Corner sessions. How he thought that the German avant-garde composer’s abstruse electronic experiments would inspire him to construct accessible songs remains a mystery. Whereas earlier milestones such as In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew deftly blended jazz, rock, and funk, On The Corner alchemized those genres until they combusted into something otherworldly and unprecedented.

On The Corner‘s first four tracks bleed into one another, an infernal medley, of which every second is loaded with portent. The record starts in media res, just as the band’s reaching a boiling point of panther-stealthy funk. Sax and trumpet dart and flow over Roy’s humid tabla patter and an OCD-groove bass line by Michael Henderson that would put a perma-grin on Holger Czukay’s mug. John McLaughlin creates utterly filthy wah-wah guitar parts, hiccuping and growling with brute eloquence, and Miles matches that with his own wah’d counterpunches. This shit is too XXX-rated for blaxploitation-flick soundtracks. There’s a Cubist aspect to the way the instruments abut one another, a disorienting legerdemain with arrangements that attest to producer Teo Macero’s mastery in the editing suite—with counsel from Mr. Davis, of course. Even when the intensity slightly diminishes, the vibe remains tense, exuding a looming danger that’s downright thrilling, thanks in part to Khalil Balakrishna and Collin Walcott’s glowering sitar drones.

“Black Satin” is the standalone standout, a blazing precursor to the drum & bass genre about 20 years before the fact. The rhythm makes it feel as if the ground is shifting beneath your feet and the Earth is spinning off its axis, as the sound whirls in five dimensions. Trust me, you’ve never heard a more disorienting use of bell tree and handclaps in your life. Listen to “Black Satin” on headphones while tripping and journey to the mountains of madness. Sly & Robbie bravely covered this on Language Barrier, but even those geniuses couldn’t match the sorcery happening here.

On the second side, “One And One” finds Henderson producing one of the illest bass tones ever, like a duck quacking after swallowing a bullfrog. Roy’s tabla and Mtume’s conga madly percolate under Miles’ poignantly undulating trumpet, and those urgent bells tickle your medulla oblongata. Toss in some of DeJohnette’s demonic cymbal work and lethal snare slaps and revel in a band cooking some of the spiciest fusion stew your ears have ever tasted.

Smashed together at album’s end, “Helen Butte” and “Mr. Freedom X” are essentially vibrant mutations of the “One And One” and “Black Satin” themes. The torque on these rhythms generates crazy sparks, with Jack and Hart’s beats hitting like sweetest revenge. These tracks tilt beyond funk into a futuristic, alien music for unfathomable rituals and contortionist sexual encounters, played by musicians with superhuman reflexes and instincts. Either that or it’s all studio magic… Either way, Miles, Jack, and company—in fact, every single person who contributed to On The Corner—became immortals for manifesting this masterpiece. -Buckley Mayfield

Located in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood, Jive Time is always looking to buy your unwanted records (provided they are in good condition) or offer credit for trade. We also buy record collections.

Great review.

My best buddies and I were in our teens and had just discovered Miles Davis a year earlier, and now had absorbed his Bitches Brew, In A Silent Way, Jack Johnson and Live/Evil albums, when we finally got to see Miles live in October 1972. “On The Corner” hadn’t come out yet, but Miles had a new band to support it. It was shocking and disorienting to us! They opened with “Chieftain,” which of course never showed up on record until many years later (in the ‘Complete On The Corner Sessions’ box). When the On The Corner album came out, it was a further shock, since it hadn’t been represented very closely by the performance we’d seen, either.

We soon grew to love “On The Corner” though for its mind-altering depth and complexity (underneath the seemingly repetitive rhythm and riffs). Other joys of the album for me are the presence of two different guitarists (McLaughlin mostly on Side 1, and David Creamer mostly on Side 2), the return of Bennie Maupin on Side 2 (ruminating freely on bass clarinet as he had done throughout Bitches Brew), and the two different saxophonists (David Liebman on Side 1 and Carlos Garnett, who was in the live band we saw that day).

My only caveat about the greatness of this album is that Columbia dropped the ball on Miles Davis and his legion of fans, by not following up on the radical new direction by releasing some of the other material from the sessions of that period. For example, Big Fun, Big Fun/Holly-wuud, Turnaround and U-Turnaround would have scored hits, and would have helped listeners make more sense of the radically different material and group sound he featured in ’72-’73 (i.e., with the electric sitar and tabla, together with heavy funk and guitar-based groove).