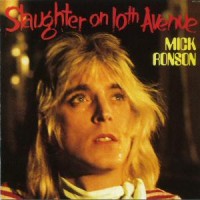

Slaughter on 10th Avenue isn’t the kind of solo effort you’d expect from [David Bowie’s] lead guitarist striking out on his own for the first time; rather, it attempts to present Ronson as a viable pop star in his own right, instead of merely giving him a forum to lay down impressive guitar solos. This is evident from the first song, a cover of Elvis Presley’s “Love Me Tender,” which starts out reverentially enough, but soon converts this gentle (or sappy depending on your taste) chestnut into an over-the-top Glam-Rock power ballad, complete with Ronson’s histrionic Bowie-esque vocals and dramatic Ziggy-style guitar work. It really should be a mess, but the song is so lovingly executed and sumptuously recorded that it simply works, and works well. Things get even more interesting on the Bowie & Ronson penned “Growing Up and I’m Fine,” which listeners will either love or hate depending on their tolerance for (or love of) Glam-Rock excess. A fey take-off on Springsteen, it’s the kind of song Bowie excelled at on albums such as Aladdin Sane, and though Ronson does a credible job on vocals, it’s impossible not to wonder what Bowie might have done with the song; nonetheless, it’s a great, glittery three-minute ride. And then there is “Music Is Lethal,” another Bowie-penned tune that starts out sounding a little like “The Port of Amsterdam,” but soon develops into a full-fledged Jacques Brel meets Scott Walker meets Bowie Glam-opera.

Overall, the production on Slaughter on 10th Avenue is consistently gorgeous and Ronno’s guitar-work is spectacular (as usual), and while this is indeed a strange album that ultimately pales in comparison to the Bowie albums it, in many ways, tries to mimic, it still manages to feel like an essential document of a brief but inspired moment when pop hooks and high art could be taken in a single dose. —LaLuna