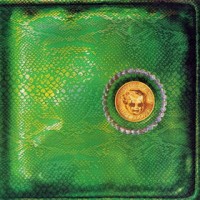

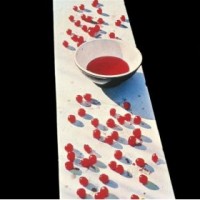

In comparison to much of the Queen back catalogue, this album has been ripped apart, criticised, and sometimes even ridiculed to the point that one begins to believe in the negativity and almost approaches this 1978 release with a view that it is going to stink however hard one tries to judge it objectively. O.K, it doesn’t contain any of the anthemic masterpieces one had become accustomed to. There is no “Bohemian Rhapsody”, “Somebody To Love”, ” We Are The Champions”, or “We Will Rock You”. Yes it does open with one of the most bizarre songs the band would ever record, the pseudo Arabesque “Mustapha”, which must have been a shock to regular fans.Yes one has to agree that their choice to stage an all nude female bicycle race at Wimbledon Racetrack and include a poster of the event with the album was not the most inspired promotonal strategy, particularly when one considers that The Womens Liberation Movement were at that time getting a certain amount of empathy for their vehement stand against Playboy, Miss World, and anything that showed women as objects for masculine amusement. Although the album would be released with the poster in the U.K, both Kmart and Sears in the States refused to handle “Jazz” with the poster, so American fans would only be able to purchase through Mail order. (It sounds like a Spinal Tap scene doesn’t it ?). The American press were particularly scathing, Rolling Stone reviewer Dave Marsh panned “Jazz”, and added “Queen may be the first truly Fascist Rock band”.

In comparison to much of the Queen back catalogue, this album has been ripped apart, criticised, and sometimes even ridiculed to the point that one begins to believe in the negativity and almost approaches this 1978 release with a view that it is going to stink however hard one tries to judge it objectively. O.K, it doesn’t contain any of the anthemic masterpieces one had become accustomed to. There is no “Bohemian Rhapsody”, “Somebody To Love”, ” We Are The Champions”, or “We Will Rock You”. Yes it does open with one of the most bizarre songs the band would ever record, the pseudo Arabesque “Mustapha”, which must have been a shock to regular fans.Yes one has to agree that their choice to stage an all nude female bicycle race at Wimbledon Racetrack and include a poster of the event with the album was not the most inspired promotonal strategy, particularly when one considers that The Womens Liberation Movement were at that time getting a certain amount of empathy for their vehement stand against Playboy, Miss World, and anything that showed women as objects for masculine amusement. Although the album would be released with the poster in the U.K, both Kmart and Sears in the States refused to handle “Jazz” with the poster, so American fans would only be able to purchase through Mail order. (It sounds like a Spinal Tap scene doesn’t it ?). The American press were particularly scathing, Rolling Stone reviewer Dave Marsh panned “Jazz”, and added “Queen may be the first truly Fascist Rock band”.

So..is “Jazz” really that bad ? Quite honestly, no it isn’t , it’s actually a good album. Ostensibly, it is the most diverse Queen album up to that period but much of the material is strong, entertaining, and one gets the impression that the band enjoyed “stretching themselves”, both musically and generically. The fun element of this recording comes through on songs like the macho Rocker “Fat Bottomed Girls”, the magnificent multi tracked Vocal arrangement on “Bicycle Race”, and the double entendre filled “Don’t Stop Me Now”, a whirling soaring Pop/Rock song on speed, and easily the best cut from the album. Freddie’s ballad “Jealousy” is gentle and sweetly performed and works well as does Brian May’s “Leaving Home Ain’t Easy”. The Roger Taylor songs are pretty bad (“Fun It”, clunky Disco Rock) and (“More Of That Jazz”, badly edited reprise music) and the John Deacon song “In Only Seven Days” seems like an act of appeasement so that all the band members can be recognised as song contributors.

“Jazz” really needs to be re-considered as a good album that was dumbed down by a Rock press who really didn’t understand that every top Rock band needs to diversify at some stage in their career, and although this isn’t Queen’s best work, it is at times both fun and entertaining. –Ben H