Rush’s first truly definitive release, 2112 kickstarts a run that would vault the power trio to the top of the heap among Canada’s rock exports. Sporting an iconic sleeve and crystal- production values, the album has come to define Rush’s early sound, featuring traditional hard rock retooled with progressive precision, while lyricist Neil Peart’s mix of philosophy and fantasy would ignite the sci-fi dreams of pimply-faced rockers for years to come. The epic title suite covers the whole of side one, and credits it’s dystopian storyline to author Ayn Rand’s Anthem, whose individualist outlook would fuel the lyrical fire of many a Rush classic. The track tells it’s Saturday afternoon story of futuristic rebellion with an interwoven set of songs ranging from the complex “Overture” section and barnstorming “Temples of Syrinx,” through the delicate “Discovery,” tortured “Soliloquy” and tear-down-the-walls “Grand Finale.” The remainder of 2112 in no way pales in comparison to it’s flip side, boasting the fan favorite wacky-tabaccy ode “A Passage to Bangkok,” supernatural imagery of “The Twilight Zone,” and self-reliant rocker “Something For Nothing.” As the critics looked on in dumbfounded disbelief, the sounds of 2112 filled the bedrooms and basements of suburban exiles worldwide, who from then on would live in anticipation of the next time they could lay their comic book ink-stained fingers on a new Rush album. –Ben

Rush’s first truly definitive release, 2112 kickstarts a run that would vault the power trio to the top of the heap among Canada’s rock exports. Sporting an iconic sleeve and crystal- production values, the album has come to define Rush’s early sound, featuring traditional hard rock retooled with progressive precision, while lyricist Neil Peart’s mix of philosophy and fantasy would ignite the sci-fi dreams of pimply-faced rockers for years to come. The epic title suite covers the whole of side one, and credits it’s dystopian storyline to author Ayn Rand’s Anthem, whose individualist outlook would fuel the lyrical fire of many a Rush classic. The track tells it’s Saturday afternoon story of futuristic rebellion with an interwoven set of songs ranging from the complex “Overture” section and barnstorming “Temples of Syrinx,” through the delicate “Discovery,” tortured “Soliloquy” and tear-down-the-walls “Grand Finale.” The remainder of 2112 in no way pales in comparison to it’s flip side, boasting the fan favorite wacky-tabaccy ode “A Passage to Bangkok,” supernatural imagery of “The Twilight Zone,” and self-reliant rocker “Something For Nothing.” As the critics looked on in dumbfounded disbelief, the sounds of 2112 filled the bedrooms and basements of suburban exiles worldwide, who from then on would live in anticipation of the next time they could lay their comic book ink-stained fingers on a new Rush album. –Ben

Rock

Randy Newman “Little Criminals” (1977)

The more I listen to Randy Newman, the more I’m impressed. It’s not his voice, even though his nasally vocal has a pleasant, relaxing quality. It’s certainly not the music which on Little Criminals is particularly one paced with a soporific, dozy aspect. It’s not even the lyrics. They can be incisive, biting and sardonic but they also are simple and endearing with a homey feel. No, it’s none of that. What it is, is the subjects he choses to write about and the subtle twists he puts into the stories. Take the title track as a prime example. Start listening to “Little Criminals” and you have this picture of indigant locals determined to rid their town of a small-time drug dealer. But, as the song progresses, you suddenly realise his protagonists are themselves criminals worried about a newcomer taking away their business – or, even better, lowering the tone of the neighbourhood because they’re into armed robbery and consider that a higher calling than drug dealing. Brilliant! Or how about “Rider In The Rain” which subverts the myth of the lone cowboy wandering the plains by reminding us of the wife he’s abandoned and the fact he’s “raped and pillaged” his way to the place he is now. Or “In Germany Before The War” which conjures up a picture of a old guy shutting up his store every day to wander down to the banks of the Rhine to gaze out over the river. Only this guy is (I think) Peter Kurten, a real-life serial killer, preying on defenceless children. And all that’s without mentioning Newman’s dig at psychiatry in “Sigmund Freud’s Impersonation Of Albert Einstein In America” or how appearances can be deceptive with “Jolly Coppers On Parade”. And another example of how satire can backfire in “Small People” which a great many people took offence to because they believed Newman was deadly serious. Although, thinking about it, I suppose it wasn’t technically a backfire as the song became a massive hit! As you would expect there are a couple of tender love songs – “Kathleen (Catholicism Made Easy)” and “I’ll Be Home”. Plus the song “Baltimore” is particularly affecting as I visited the city very recently. I think there must have been a great deal of urban regeneration since that song was written because Newman’s Baltimore is a far bleaker and darker place than I saw. I don’t think Newman will ever release a classic album because of the way he writes. The uncertainty of the does he mean it? is he joking? is unsettling and uncomfortable and makes it impossible to like everything. But I’m equally convinced that, after hearing just two of his albums, there will always be something for me to enjoy on all his others. –Ian

The more I listen to Randy Newman, the more I’m impressed. It’s not his voice, even though his nasally vocal has a pleasant, relaxing quality. It’s certainly not the music which on Little Criminals is particularly one paced with a soporific, dozy aspect. It’s not even the lyrics. They can be incisive, biting and sardonic but they also are simple and endearing with a homey feel. No, it’s none of that. What it is, is the subjects he choses to write about and the subtle twists he puts into the stories. Take the title track as a prime example. Start listening to “Little Criminals” and you have this picture of indigant locals determined to rid their town of a small-time drug dealer. But, as the song progresses, you suddenly realise his protagonists are themselves criminals worried about a newcomer taking away their business – or, even better, lowering the tone of the neighbourhood because they’re into armed robbery and consider that a higher calling than drug dealing. Brilliant! Or how about “Rider In The Rain” which subverts the myth of the lone cowboy wandering the plains by reminding us of the wife he’s abandoned and the fact he’s “raped and pillaged” his way to the place he is now. Or “In Germany Before The War” which conjures up a picture of a old guy shutting up his store every day to wander down to the banks of the Rhine to gaze out over the river. Only this guy is (I think) Peter Kurten, a real-life serial killer, preying on defenceless children. And all that’s without mentioning Newman’s dig at psychiatry in “Sigmund Freud’s Impersonation Of Albert Einstein In America” or how appearances can be deceptive with “Jolly Coppers On Parade”. And another example of how satire can backfire in “Small People” which a great many people took offence to because they believed Newman was deadly serious. Although, thinking about it, I suppose it wasn’t technically a backfire as the song became a massive hit! As you would expect there are a couple of tender love songs – “Kathleen (Catholicism Made Easy)” and “I’ll Be Home”. Plus the song “Baltimore” is particularly affecting as I visited the city very recently. I think there must have been a great deal of urban regeneration since that song was written because Newman’s Baltimore is a far bleaker and darker place than I saw. I don’t think Newman will ever release a classic album because of the way he writes. The uncertainty of the does he mean it? is he joking? is unsettling and uncomfortable and makes it impossible to like everything. But I’m equally convinced that, after hearing just two of his albums, there will always be something for me to enjoy on all his others. –Ian

Jellyfish “Bellybutton” (1990)

From The Beatles right through to the likes of The Lightning Seeds, Britain has a knack of producing bands who deliver a brand of pure, polished pop. The content may have dark or serious overtones but the melody and vocals carry a rare, unblemished character. When a band is lauded as new pop sensations in America don’t expect the same characteristics. In some respects our pop is their AOR whilst their pop arrives way over from left field. They Might Be Giants and Eels are good illustrations of this idiosyncrasy and Jellyfish can be added to that list. They may have more rounded edges than the others but, underneath, they are equally strange. Vocally the closest comparison to Jellyfish is Crowded House (Andy Sturmer even sounds like Neil Finn), but when it comes to lyrical content they are a mile apart. Absent fathers (“The Man I Used To Be”), prostitution (“The King Is Half Undressed”), marital abuse (“She Still Loves Him”), rampant consumerism and parental neglect (“All I Want Is Everything”) are all covered. It’s testimony to the skill of the band that, no matter how heavy the subject, the music retains a lightness of touch to stop proceedings becoming too maudlin. Special mention should also be given to “I Wanna Stay Home” and “Baby’s Coming Back” which, on their own, prove that Jellyfish was definitely a band that got away. –Ian

From The Beatles right through to the likes of The Lightning Seeds, Britain has a knack of producing bands who deliver a brand of pure, polished pop. The content may have dark or serious overtones but the melody and vocals carry a rare, unblemished character. When a band is lauded as new pop sensations in America don’t expect the same characteristics. In some respects our pop is their AOR whilst their pop arrives way over from left field. They Might Be Giants and Eels are good illustrations of this idiosyncrasy and Jellyfish can be added to that list. They may have more rounded edges than the others but, underneath, they are equally strange. Vocally the closest comparison to Jellyfish is Crowded House (Andy Sturmer even sounds like Neil Finn), but when it comes to lyrical content they are a mile apart. Absent fathers (“The Man I Used To Be”), prostitution (“The King Is Half Undressed”), marital abuse (“She Still Loves Him”), rampant consumerism and parental neglect (“All I Want Is Everything”) are all covered. It’s testimony to the skill of the band that, no matter how heavy the subject, the music retains a lightness of touch to stop proceedings becoming too maudlin. Special mention should also be given to “I Wanna Stay Home” and “Baby’s Coming Back” which, on their own, prove that Jellyfish was definitely a band that got away. –Ian

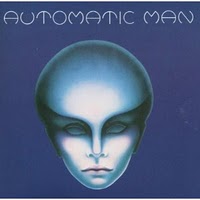

Automatic Man “Automatic Man” (1976)

There he is again. That Blue Space Alien staring out, empty-eyed from my LP collection. As if using telepathy, he beckons me to reach out for him, pull out his vinyl body and put him my turntable. It’s funny how after all these years since I first saw him in the record bins at Peaches Records in Ohio, he still has that effect on me. But I know the real lure of this LP is not the Alien, but the Space-Fusion Prog of the band, that brings me back to play that album. Automatic Man’s debut LP, in my opinion is on the best of the fusion/prog era, perhaps equaling Return To Forever’s classic Romantic Warrior.

There he is again. That Blue Space Alien staring out, empty-eyed from my LP collection. As if using telepathy, he beckons me to reach out for him, pull out his vinyl body and put him my turntable. It’s funny how after all these years since I first saw him in the record bins at Peaches Records in Ohio, he still has that effect on me. But I know the real lure of this LP is not the Alien, but the Space-Fusion Prog of the band, that brings me back to play that album. Automatic Man’s debut LP, in my opinion is on the best of the fusion/prog era, perhaps equaling Return To Forever’s classic Romantic Warrior.

Automatic Man was a super-group of sorts. The self-titled debut album featured a stellar lineup: Keyboard player and singer Bayete, whose voice eerily resembles Jimi Hendrix, played with Stanley Clark. S.F. Bay area musician Doni Harvey, ex-Gong, played bass. Pat Thrall, was a member of Stomu Yamashita’s band Go, was on guitar. Formerly of Santana, legendary percussionist Michael Shrieve blazed on drums.

This isn’t a loose jam session or self-indulgent doodling, this is an album driven by strong songwriting. The opening “Atlantis Rising/Comin’Through” displays a sound that manages to keep its footings firmly in the here and now, whilst simultaneously oozing an air of futuristic soundscapes that render it ripe for evoking mental imagery. Power number “My Pearl”, with its driving funk/synth vibe, demonstrate that Automatic Man had the chops to craft a pop single. Pat Thrall’s riffs even give you the impression that Hendrix has been transported back from the dead to appear, or even cloned! You got to check out Thrall’s the guitar solo on the title track. It’s got to be the best solo that no one has ever heard! The lush keyboard arrangements add a reverberating layer of an almost alien-like displacement to the overall sound of the proceedings. Meanwhile, breezier numbers such as “One ‘N One” and “Newspapers” exhibit a more other-worldly, cold sound, as if lying on a beach on Pluto (does Pluto have beaches?)

Space references aside, this album really rocks. There is no filler on this LP and is truly a satisfying listen. If you see the Blue Alien, let him beam you aboard for the ride. –Ed

Mike Oldfield “Tubular” Bells (1973)

It’s difficult to asess the importance of “Tubular Bells” and indeed the career of Mike Oldfield without reference to two important figures who contributed to the success of the album, Richard Branson and William Friedkin. The 19 year old Oldfield had used valuable studio time funded by Branson, to record his debut, then titled “Opus 1”. Oldfield then hawked this work around the major record companies to complete rejection, and Branson, who at that time ran a mail order company, decided to form his own record company (Virgin), and release this (retitled “Tubular Bells”) as the inaugural record. William Friedkin was at this time Directing the ground breaking horror flick “The Exorcist”, and having heard “Tubular Bells” decided to use the opening eerie tinkling piano intro, decided to use it as the title music for the movie. And so, the die was cast and the album would go on to sell sixteen million copies worldwide, win Oldfield a Grammy award, and develop a new genre of music. It’s difficult to review “Tubular Bells” as a straight Popular, Classical or Rock recording. It contains all of these genres and more, classically structured, it’s a complex, startlingly unique, and undoubtedly valiant recording. At times the sound is beautifully symphonic, at other times hauntingly powerful. Oldfield uses over thirty different musical instruments and probably just as many percussive instruments, to create a plethora of differing interludes, some gentle, some sonically robust, all linked together by intricate tempo changes perfectly exemplified about twelve minutes into side one where a delicately intricate section is cleverly interrupted by rifferama guitar crash chords which fade into the next musical excursion. The album finishes with a traditional English folk tune which perfectly concludes a divinely satisfying album. Some Oldfield fans argue that “Hergest Ridge” and “Ommadawn” are better musical performances, but I stoutly defend “Tubular Bells” because of its bravery, complexity and utter originality. “Tubular Bells” remains a colossal achievement. –Ben H

It’s difficult to asess the importance of “Tubular Bells” and indeed the career of Mike Oldfield without reference to two important figures who contributed to the success of the album, Richard Branson and William Friedkin. The 19 year old Oldfield had used valuable studio time funded by Branson, to record his debut, then titled “Opus 1”. Oldfield then hawked this work around the major record companies to complete rejection, and Branson, who at that time ran a mail order company, decided to form his own record company (Virgin), and release this (retitled “Tubular Bells”) as the inaugural record. William Friedkin was at this time Directing the ground breaking horror flick “The Exorcist”, and having heard “Tubular Bells” decided to use the opening eerie tinkling piano intro, decided to use it as the title music for the movie. And so, the die was cast and the album would go on to sell sixteen million copies worldwide, win Oldfield a Grammy award, and develop a new genre of music. It’s difficult to review “Tubular Bells” as a straight Popular, Classical or Rock recording. It contains all of these genres and more, classically structured, it’s a complex, startlingly unique, and undoubtedly valiant recording. At times the sound is beautifully symphonic, at other times hauntingly powerful. Oldfield uses over thirty different musical instruments and probably just as many percussive instruments, to create a plethora of differing interludes, some gentle, some sonically robust, all linked together by intricate tempo changes perfectly exemplified about twelve minutes into side one where a delicately intricate section is cleverly interrupted by rifferama guitar crash chords which fade into the next musical excursion. The album finishes with a traditional English folk tune which perfectly concludes a divinely satisfying album. Some Oldfield fans argue that “Hergest Ridge” and “Ommadawn” are better musical performances, but I stoutly defend “Tubular Bells” because of its bravery, complexity and utter originality. “Tubular Bells” remains a colossal achievement. –Ben H

Devo “Are We Not Men?” (1978)

Imagine the scene. The house lights dim on an expectant crowd. It’s difficult to see through the darkness but the swish of heavy fabric announces the stage curtains being drawn back. The spots slowly rise on a stage shrouded in a huge sheet of black plastic which rises to cover the vague shape of a drum-kit. A bright beam of white light picks out movement from under the sheet and flashes off a number of blades which pierce the plastic and slash vicious tears into the black skin. Like a sci-fi caesarean Devo push themselves through, clutching instruments and dressed in vivid yellow boiler suits. It takes a little time to rip the sheet away from the drums before they launch into “Uncontrollable Urge”, but it’s still got to be one of the best entrances ever.

Imagine the scene. The house lights dim on an expectant crowd. It’s difficult to see through the darkness but the swish of heavy fabric announces the stage curtains being drawn back. The spots slowly rise on a stage shrouded in a huge sheet of black plastic which rises to cover the vague shape of a drum-kit. A bright beam of white light picks out movement from under the sheet and flashes off a number of blades which pierce the plastic and slash vicious tears into the black skin. Like a sci-fi caesarean Devo push themselves through, clutching instruments and dressed in vivid yellow boiler suits. It takes a little time to rip the sheet away from the drums before they launch into “Uncontrollable Urge”, but it’s still got to be one of the best entrances ever.

Far more guitar-led than their later releases, Are We Not Men? Was considered radical upon its release in 1978. Much closer to the punk revolution than is realised, Devo savaged the American materialistic way of life and dared to suggest that humankind was de-evolving. From sex related psycho-babble (“Uncontrollable Urge”) to satellites falling from the sky (“Space Junk”), from consumerism (“Too Much Paranoias”) to genetics (“Mongoloid”), this is a very strange and, on one plain, deeply disturbing album. It remains a powerful indictment of the human condition. –Ian

Montrose “Montrose” (1973)

Arguably the greatest American hard rock album ever, Montrose’s 1973 debut is a stunning display of instrumental and vocal prowess. As the prototypical 4-piece – guitar/vocals/bass/drums – they recorded one of the all-time essential slabs of heavy rock. Ronnie Montrose makes a tremendous leap from in-demand session musician to bandleader and legit guitar hero, Sam Hagar (wasn’t even Sammy yet) sets the standard for American rock vocals, Bill “the Electric” Church lays down some amazingly fat basslines, and Denny Carmassi smacks his drums with intense precision and manly vigor.

Arguably the greatest American hard rock album ever, Montrose’s 1973 debut is a stunning display of instrumental and vocal prowess. As the prototypical 4-piece – guitar/vocals/bass/drums – they recorded one of the all-time essential slabs of heavy rock. Ronnie Montrose makes a tremendous leap from in-demand session musician to bandleader and legit guitar hero, Sam Hagar (wasn’t even Sammy yet) sets the standard for American rock vocals, Bill “the Electric” Church lays down some amazingly fat basslines, and Denny Carmassi smacks his drums with intense precision and manly vigor.

Montrose is a truly groundbreaking album, wildly influential on future generations of hard rock and metal bands. Incredibly tight, musically exciting, with relatively short songs (for the era) Montrose forged a new, bracingly kinetic sound, fresher than the competition. Eschewing the lengthy jamming of Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple, much less crushingly heavy than Black Sabbath, not needing the theatricality of Alice Cooper or Kiss or Queen, more talented and less over-reaching than Grand Funk, tighter than BTO or The Amboy Dukes, less overtly boogie/blues oriented and more streamlined than Foghat or the James Gang, less ponderous than Rush or Uriah Heep, less myopic than Mahoghany Rush, not at all scary like early BOC, more catchy than Cactus or Crow, harder rocking than the southern rock bands. Note: I honestly adore all (well, most) of the above-mentioned bands, I’m just using them for contrast.

Sammy Hager and Ronnie Montrose managed one more album together (1974’s fine Paper Money) before collapsing under the weight of the two competing gigantic egos, but the debut album is the real classic. Montrose has always had a permanent high spot on my top-ten “desert island disc” list. At least three songs on this album still make frequent rotation on most hard rock and classic rock stations, at least on the West Coast. Both Hagar and Ronnie Montrose admit it was a career peak. Say, how about a reunion album and tour while we’re dreaming? Crank it on up! —Darerock

Silver Apples “Silver Apples” (1968)

Considering that this kind of music was released in 1968 is amazing, but even more amazing is that it still kicks the ass of every other electro-pop-band, save perhaps Kraftwerk. The oscillators flow wildly, the drums lay mindnumbing beats and the lyrics, maybe hippie-esque considering the day, somehow seem ageless still. And it’s unbelievably catchy, like in a pop way. I could tell a funny tale about Syd Barrett finding a Close Encounters of the Third Kind-style alien mothership wrecked somewhere in the forest and going all circuit breaking on the mushrooms, but I won’t. Pioneering and reigning still. All hail the whirly-bird! –Tuukka

Considering that this kind of music was released in 1968 is amazing, but even more amazing is that it still kicks the ass of every other electro-pop-band, save perhaps Kraftwerk. The oscillators flow wildly, the drums lay mindnumbing beats and the lyrics, maybe hippie-esque considering the day, somehow seem ageless still. And it’s unbelievably catchy, like in a pop way. I could tell a funny tale about Syd Barrett finding a Close Encounters of the Third Kind-style alien mothership wrecked somewhere in the forest and going all circuit breaking on the mushrooms, but I won’t. Pioneering and reigning still. All hail the whirly-bird! –Tuukka

Replacements “Let It be” (1984)

For me this is far and away the best album The Replacements ever made. Some people say that they wish rock and roll was always imbued with the spirit that The Clash brought to it on “London Calling”. I could easily say the same thing about “Let it Be”. This is the perfect synthesis of rock aggression and songwriting finesse. A song like “Androgynous” probably wouldn’t move me so much if it had been more slickly produced. The raw beauty of these songs makes me believe in them. There have been a million songs written about adolescence but “Sixteen Blue” is one of the only ones that really feels like it. The painful yearning and confusion of being sixteen is captured perfectly in those crunching guitar chords and especially the guitar solo with which the song closes. Rather than offering release, the end of the song raises the unresolved tension higher and higher. It is full of beauty and sadness. And then we have the album closer, “Answering Machine”, with its fabulous, tight guitar playing, its earnest, pleading vocal and gorgeous melodicism. This is one of the best songs ever written about romantic obsession. Indeed this is one of the best rock songs period. In its rawness, energy and its dual loyalties to grunge and melody, in 1984 this album sounded like the future itself. –Javasean

For me this is far and away the best album The Replacements ever made. Some people say that they wish rock and roll was always imbued with the spirit that The Clash brought to it on “London Calling”. I could easily say the same thing about “Let it Be”. This is the perfect synthesis of rock aggression and songwriting finesse. A song like “Androgynous” probably wouldn’t move me so much if it had been more slickly produced. The raw beauty of these songs makes me believe in them. There have been a million songs written about adolescence but “Sixteen Blue” is one of the only ones that really feels like it. The painful yearning and confusion of being sixteen is captured perfectly in those crunching guitar chords and especially the guitar solo with which the song closes. Rather than offering release, the end of the song raises the unresolved tension higher and higher. It is full of beauty and sadness. And then we have the album closer, “Answering Machine”, with its fabulous, tight guitar playing, its earnest, pleading vocal and gorgeous melodicism. This is one of the best songs ever written about romantic obsession. Indeed this is one of the best rock songs period. In its rawness, energy and its dual loyalties to grunge and melody, in 1984 this album sounded like the future itself. –Javasean

Blood, Sweat & Tears “Child Is Father to the Man” (1968)

It’s easy to overlook the ubiquitous Blood, Sweat & Tears as their LPs seem to be present in almost every dollar bin in every city. Spend the buck! Their debut is an essential listen and features the unpredictable Al Kooper at the peak of his powers. The music is an eclectic fusion of progressive and psychedelic rock, blues and jazz. There are even elements of lounge music, and occasional orchestration added to the mix. The album features eight originals and four covers. The best covers are Randy Newman’s uplifting Just One Smile and Carole King’s So Much Love which closes the album. Most of the originals were composed by Al Kooper. His bizarre Overture opens, with it’s enticing orchestrated music joined by some manic laughing. Kooper’s I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know is an excellent jazzed-up blues song and Something Goin’ On is a great jam that was an essential part of late 60s progressive rock. Child Is Father to the Man is an excellent experimental rock album and an important part of any 60s pop collection. –Jim

It’s easy to overlook the ubiquitous Blood, Sweat & Tears as their LPs seem to be present in almost every dollar bin in every city. Spend the buck! Their debut is an essential listen and features the unpredictable Al Kooper at the peak of his powers. The music is an eclectic fusion of progressive and psychedelic rock, blues and jazz. There are even elements of lounge music, and occasional orchestration added to the mix. The album features eight originals and four covers. The best covers are Randy Newman’s uplifting Just One Smile and Carole King’s So Much Love which closes the album. Most of the originals were composed by Al Kooper. His bizarre Overture opens, with it’s enticing orchestrated music joined by some manic laughing. Kooper’s I Love You More Than You’ll Ever Know is an excellent jazzed-up blues song and Something Goin’ On is a great jam that was an essential part of late 60s progressive rock. Child Is Father to the Man is an excellent experimental rock album and an important part of any 60s pop collection. –Jim

Kiss “Kiss” (1974)

Before the merchandising, neon spandex, and nostalgia circuit, KISS were just another hard rock band with stars in/on their eyes. Kiss, the debut, is loaded with future klassics that display the Stanley/Simmons partnership’s knack for grafting pop hooks to bludgeoning riffs, sporting the likes of “Deuce,” “Strutter,” “Nothin’ to Lose,” and immortal hooker drama “Black Diamond,” a vocal-shy Ace checking in with urban intoxication anthem “Cold Gin,” and an overlooked gem in the simple charm of “Let Me Know.” While the less said about the “Kissin’ Time” cover grafted on to later pressings, the better, and ignoring the fact that a certain sluggishness drags some of these recordings down compared to their Alive! revamps, Kiss remains an auspicious debut. –Ben

Before the merchandising, neon spandex, and nostalgia circuit, KISS were just another hard rock band with stars in/on their eyes. Kiss, the debut, is loaded with future klassics that display the Stanley/Simmons partnership’s knack for grafting pop hooks to bludgeoning riffs, sporting the likes of “Deuce,” “Strutter,” “Nothin’ to Lose,” and immortal hooker drama “Black Diamond,” a vocal-shy Ace checking in with urban intoxication anthem “Cold Gin,” and an overlooked gem in the simple charm of “Let Me Know.” While the less said about the “Kissin’ Time” cover grafted on to later pressings, the better, and ignoring the fact that a certain sluggishness drags some of these recordings down compared to their Alive! revamps, Kiss remains an auspicious debut. –Ben

The Fixx “Reach the Beach” (1983)

I remember seeing The Fixx on MTV when I was 13, there was always this dark sophistication surrounding them. Their sophomore album, Reach the Beach lives up to those first impressions. This record was quite a success for them with the hits “Saved by Zero”, a complex tune with a hopeless optimism that seems to clash with the melody & “One thing Leads to Another”, an almost dance track about deceit in relationships. The rest of the record follows suit with clean, chorus drenched guitar licks, snappy bass slaps, dissonant keyboards & those wonderful synthesized drums we all loved from the eighties. Cy Curnin’s vocals croon like The Cure’s Robert Smith trying to imitate Duran Duran’s Simon Le Bon, in fact, the music could be described in the same way, new wave funkiness with a sense of melancholy underneath it all- like trying to dance when your sad. Slightly cynical lyrics with upbeat, yet complex arrangements spare this record from being another eighties novelty, the contradictions keep it real. –ECM Tim

I remember seeing The Fixx on MTV when I was 13, there was always this dark sophistication surrounding them. Their sophomore album, Reach the Beach lives up to those first impressions. This record was quite a success for them with the hits “Saved by Zero”, a complex tune with a hopeless optimism that seems to clash with the melody & “One thing Leads to Another”, an almost dance track about deceit in relationships. The rest of the record follows suit with clean, chorus drenched guitar licks, snappy bass slaps, dissonant keyboards & those wonderful synthesized drums we all loved from the eighties. Cy Curnin’s vocals croon like The Cure’s Robert Smith trying to imitate Duran Duran’s Simon Le Bon, in fact, the music could be described in the same way, new wave funkiness with a sense of melancholy underneath it all- like trying to dance when your sad. Slightly cynical lyrics with upbeat, yet complex arrangements spare this record from being another eighties novelty, the contradictions keep it real. –ECM Tim