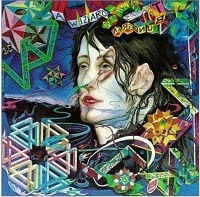

Spirit was (and still is) sadly one of the most overlooked bands from the psychedelic era – perhaps it was the fact that the music was more akin to Soft Machine and other jazz-oriented bands of the day during the era when country/rock (the Dead, Flying Burrito Brothers, Poco, etc) began to dominate California rock… whatever the reason, Spirit deserves greater attention and praise than it has received.

While they DID score a surprise hit in 1968 with “I Got a Line on You,” it is without question the 1970 concept lp “The 12 Dreams of Dr.Sardonicus” that will forever define the band. The songs, like the talent in the band, are enormous and special, spanning the gamut from the jazzy blues of the wonderful “Mr. Skin” (tribute to drummer Cassidy) to the out and out psychedelia of the gorgeous “Love has Found a Way,” to the surrealism of “Animal Zoo.”

“12 Dreams” remains one of the most consistent listens that I own from late 60’s/early 70’s rock n roll. This is due most to the brilliant musicianship of Jay Ferguson, John Locke, Mark Andes, Ed Cassidy, and Randy California. The wonderful interplay between these men is top-rate, with California’s brilliance on the guitar meshing perfectly with stepfather Cassidy’s jazzy drumming (he was drummer for the Rising Sons, featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder). The songs, as I mentioned earlier, are brilliant and flow wonderfully. The combination of the two equals an album that I can’t put down for very long.

Fans of late 60’s rock know about Spirit. The time has come for the rest of the world to do the same. One of the most underrated and brilliant lps ever made. Period. —Steve