Yes, I think this is even better than The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. The difference is while that record gets its strength from its total weirdness — it meanders in the best sense — this one has actual songs: great, great songs that will move you, make you laugh and make you think. “First Girl I Loved” alone is enough to get you seeking out this record, but add to that the prescient sarcasm of “Back In The 1960s” (which foresees the death of the hippie ideal before it had even begun), the Wind In The Willows on acid of “Little Cloud” and “The Hedgehog Song” (The Archbishop of Canterbury’s fave ISB number!) and the simply beautiful “Painting Box”. Plus I love the way Williamson sings. For those of you who wonder what “The Fool On The Hill” would have been liked if Lennon had written it. –Brad

Yes, I think this is even better than The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter. The difference is while that record gets its strength from its total weirdness — it meanders in the best sense — this one has actual songs: great, great songs that will move you, make you laugh and make you think. “First Girl I Loved” alone is enough to get you seeking out this record, but add to that the prescient sarcasm of “Back In The 1960s” (which foresees the death of the hippie ideal before it had even begun), the Wind In The Willows on acid of “Little Cloud” and “The Hedgehog Song” (The Archbishop of Canterbury’s fave ISB number!) and the simply beautiful “Painting Box”. Plus I love the way Williamson sings. For those of you who wonder what “The Fool On The Hill” would have been liked if Lennon had written it. –Brad

Jive Time Turntable

Terje Rypdal “Odyssey” (1975)

Producer Manfred Eicher’s ECM label has been a mixed bag over the years. Much of the output has been criticized for being homogenized, self-indulgent & dull as well as being praised for genius production, adventurous artists making groundbreaking recordings, with an inner fire underneath the slick recordings. Love it or hate it, there is a definite sound environment that Eicher has created, it’s simply known as the “ECM sound”. The use of space in music, as loud as silence, free improv without a million notes, composed chaos that whispers screams. When it works it is timeless & innovative, when it doesn’t, it can sound like elevator music that was thrown aside because it sounded too much like, well, elevator music.

Producer Manfred Eicher’s ECM label has been a mixed bag over the years. Much of the output has been criticized for being homogenized, self-indulgent & dull as well as being praised for genius production, adventurous artists making groundbreaking recordings, with an inner fire underneath the slick recordings. Love it or hate it, there is a definite sound environment that Eicher has created, it’s simply known as the “ECM sound”. The use of space in music, as loud as silence, free improv without a million notes, composed chaos that whispers screams. When it works it is timeless & innovative, when it doesn’t, it can sound like elevator music that was thrown aside because it sounded too much like, well, elevator music.

Odyssey is guitarist Terje Rypdal’s fourth record for ECM & it works. A double album of low-fi fusion intertwined with progressive rock string interludes, distorted organs, hissy snare fills, groovy bass lines , ethereal horns, & of course, Rypdal’s guitar playing, which sounds like a cross between Jimi Hendrix & an avant garde cello player. The melodies are dark, cold & funky as hell. Rypdal was definitely channeling Miles Davis’ “Bitches Brew” on this record but only softer, all the groove & dissonance, but less crowded, like someone whispering a hurricane in your ear. The record opens with “Darkness Falls”. Rypdal’s guitar screeching like an injured space bird along side organ stabs & chattering drums with the bass searching for a cohesive rhythm: a gentle panic within the group forms but slowly subsides as the sound fades & flows right into the second track, “Midnite”. Warm, pulsating bass & drums lock into each other & they begin to groove with Rypdal’s wah pedal over the top of moaning trombones & snaky organ lines in the background, holding it all together; quietly. Odyssey has it’s heavier moments as well- “Rolling Stone” a twenty-five minute rock-funk gem that sounds as if Sly Stone & crew ran into the boys from Black Sabbath & said, “Let’s jam”. “Over Birkerot” would be perfectly comfortable on a mid- seventies King Crimson record. It does bog down a bit with a couple of almost contemporary classical string/synthesizer drone marathons that can get a little sleepy, but there’s just enough smolder in there to keep the listener curious. The tracks heard on Odyssey still sound relevant. Manfred Eicher’s production stamp make these tunes sound as if they could be on any modern down-tempo electronic record from today. –ECM Tim

Buffalo Springfield “Buffalo Springfield Again” (1967)

Just a little over 30 minutes long, and it goes in about as many directions. Neil Young’s songs don’t seem to belong on the same record as those of Stills or Furay; actually, they don’t seem to belong in the same universe. Yet the record as a whole doesn’t seem messy at all, but powerful, even focused, by its diversity. I used to love the Young songs — even the psychedelic weirdness of “Broken Arrow” — but these days I find myself attracted to the Stills songs, which are some of his best. “Bluebird” in particular manages to seem both sleek and cryptic at the same time, and the Stills-Young guitar team is a wonder (take that, Yardbirds!). Really, the only clunker is the Dewey Martin-sung “Good Time Boy”, a fairly terrible Otis parody (but at least it adds soul to the band’s armory). Everything else works, even “Mr Soul”, on which Neil borrows a riff from the Rolling Stones. And not for the last time, either. –Brad

Just a little over 30 minutes long, and it goes in about as many directions. Neil Young’s songs don’t seem to belong on the same record as those of Stills or Furay; actually, they don’t seem to belong in the same universe. Yet the record as a whole doesn’t seem messy at all, but powerful, even focused, by its diversity. I used to love the Young songs — even the psychedelic weirdness of “Broken Arrow” — but these days I find myself attracted to the Stills songs, which are some of his best. “Bluebird” in particular manages to seem both sleek and cryptic at the same time, and the Stills-Young guitar team is a wonder (take that, Yardbirds!). Really, the only clunker is the Dewey Martin-sung “Good Time Boy”, a fairly terrible Otis parody (but at least it adds soul to the band’s armory). Everything else works, even “Mr Soul”, on which Neil borrows a riff from the Rolling Stones. And not for the last time, either. –Brad

Polskie Nagrania

Check out our guest post on our favorite image related blog, 50 Watts. The post features our personal collection of Polish record covers put out by Polskie Nagrania Muza.

Polskie Nagrania “Muza” (Polish Records ‘Muse’) is a major state-owned record label located in Warsaw. It was established in 1956 after the merger of the vinyl record factory “Muza” and the record house Polskie Nagrania (with the history of the latter traced to the Interbellum times). It has been producing a wide range of musical records from pop, rock, jazz, folk and classical.

These sleeves showcase the unique style of Polish graphic design in the mid century including a few poster design heavyweights like Jerzy Flisak and Rafal Olbinski. Visit the Gallery›

The Mahavishnu Orchestra “The Inner Mounting Flame” (1971)

Fusion has become a dirty word in most jazz circles these days, which have been thoroughly Marsalis-ised to the point of declaring that the only good jazz is acoustic jazz. And yes, there were a lot of crimes committed in the name of jazz-rock (I’d rather have my fingernails pulled out than have to listen to a Lenny White LP again) but a handful of classics did emerge from it. This is one. I’m tempted to say this is THE one, which wouldn’t be correct, but you do tend to get carried away listening to McLaughlin and the boys in full flight. As opposed to their subsequent albums, the emphasis here is on virtuoso playing that still comes from the heart. And the all-acoustic “A Lotus on Irish Streams” is quite simply one of the most beautiful pieces of music to come out of the 1970s. In some ways Birds of Fire is a better, more ambitious and fully-conceived album than this one, but it just misses out on the questing spirit and beauty that makes The Inner Mounting Flame such a compelling listening experience. –Brad

Fusion has become a dirty word in most jazz circles these days, which have been thoroughly Marsalis-ised to the point of declaring that the only good jazz is acoustic jazz. And yes, there were a lot of crimes committed in the name of jazz-rock (I’d rather have my fingernails pulled out than have to listen to a Lenny White LP again) but a handful of classics did emerge from it. This is one. I’m tempted to say this is THE one, which wouldn’t be correct, but you do tend to get carried away listening to McLaughlin and the boys in full flight. As opposed to their subsequent albums, the emphasis here is on virtuoso playing that still comes from the heart. And the all-acoustic “A Lotus on Irish Streams” is quite simply one of the most beautiful pieces of music to come out of the 1970s. In some ways Birds of Fire is a better, more ambitious and fully-conceived album than this one, but it just misses out on the questing spirit and beauty that makes The Inner Mounting Flame such a compelling listening experience. –Brad

Muddy Waters “Electric Mud” (1968)

This may be the most polarizing album ever to come out of the Chess empire (unless that Rotary Connection Christmas album really drives you batty); it’s telling that they chose to release this on the more daring Cadet Concept subsidiary. It’s funny to think that this album was intended to update Muddy Waters’ image to appeal to the younger people and, 42 years on, that’s exactly what it did for me, who currently fits the original demographic they were after: I have no quarrel with traditional blues, I even enjoy it when the mood strikes me, but this is the only Muddy Waters album that I beat the proverbial door down to acquire. And this album is ferocious! There’s no session information given but I would have to imagine that it’s the usual Chess/Cadet session crew backing him up. The bass rumbles along louder than I’ve ever heard John Paul Jones’ or John Entwistle’s. The drums, in particular the bass drum, are louder than those in any psych group I can think of other than maybe the Move. The most surprising aspect may be that, despite the fact that Muddy reportedly hated this album with a passion, his electric guitar playing is phenonmenal. I suppose this is expected from a great bluseman, but he also knows how to use its new-found volume and distortion to great effect. He growls through each monster track, achieving what Jimi Hendrix was ly after in his formative days. As it is a late 60s Cadet Concept album, the ace in the hole is the arrangement, this time from the great Charles Stepney, in the midst of arranging the hell out of those Rotary Connection and Ramsey Lewis albums (the latter along with Richard Evans). Stepney actually displays quite a bit of restraint here, with his patented complex string and brass parts lurking way in the background, the exception being when “She’s Alright” brilliantly morphs it’s coda into the string-laden bridge from “My Girl”.

This may be the most polarizing album ever to come out of the Chess empire (unless that Rotary Connection Christmas album really drives you batty); it’s telling that they chose to release this on the more daring Cadet Concept subsidiary. It’s funny to think that this album was intended to update Muddy Waters’ image to appeal to the younger people and, 42 years on, that’s exactly what it did for me, who currently fits the original demographic they were after: I have no quarrel with traditional blues, I even enjoy it when the mood strikes me, but this is the only Muddy Waters album that I beat the proverbial door down to acquire. And this album is ferocious! There’s no session information given but I would have to imagine that it’s the usual Chess/Cadet session crew backing him up. The bass rumbles along louder than I’ve ever heard John Paul Jones’ or John Entwistle’s. The drums, in particular the bass drum, are louder than those in any psych group I can think of other than maybe the Move. The most surprising aspect may be that, despite the fact that Muddy reportedly hated this album with a passion, his electric guitar playing is phenonmenal. I suppose this is expected from a great bluseman, but he also knows how to use its new-found volume and distortion to great effect. He growls through each monster track, achieving what Jimi Hendrix was ly after in his formative days. As it is a late 60s Cadet Concept album, the ace in the hole is the arrangement, this time from the great Charles Stepney, in the midst of arranging the hell out of those Rotary Connection and Ramsey Lewis albums (the latter along with Richard Evans). Stepney actually displays quite a bit of restraint here, with his patented complex string and brass parts lurking way in the background, the exception being when “She’s Alright” brilliantly morphs it’s coda into the string-laden bridge from “My Girl”.

Most blues purists decry this, which I suppose is understandable, but you have to admit that this is as convincing a psychedelic-blues album as anything Cream or Led Zeppelin could hope to come up with. Still underrated by most critics, this is truly a left-field masterpiece. –Mike

The Stooges “Raw Power” (1973)

“The raw power of Iggy Pop predated punk.” An anonymous quote I heard from some time back that sums up the very essence of what Iggy and the Stooges were about. And with their 1973 release, Raw Power, their muscle is in full-flex-mode. Famously produced by, David Bowie, and the band in a state of disorder – the combining couple crafted an album that, not only became a trailblazer, but also set the tone for what would come next, punk. Because of this, Raw Power, was molded into the blueprint of how rock ‘n’ roll should always be: dark, dangerous, and full of filth. The out of ordinary sound for its time has still never been equaled, many imitators came and went, struggling with the crass intensity, but they were all failed attempts. Iggy made a point to declare conventionalism was out, and in its place — sleazy drug-fueled globs of noise. The Stooges remain one of my all-time favorite bands. And it has a lot to do with Raw Power. Some hipsters might declare, Raw Power, the weakest out of the holy trinity, due to its heavy praise, but there’s no denying its incendiary explosive strength. And on more than one occasion, I have been known to declare it my favorite album, ever. –Jason

“The raw power of Iggy Pop predated punk.” An anonymous quote I heard from some time back that sums up the very essence of what Iggy and the Stooges were about. And with their 1973 release, Raw Power, their muscle is in full-flex-mode. Famously produced by, David Bowie, and the band in a state of disorder – the combining couple crafted an album that, not only became a trailblazer, but also set the tone for what would come next, punk. Because of this, Raw Power, was molded into the blueprint of how rock ‘n’ roll should always be: dark, dangerous, and full of filth. The out of ordinary sound for its time has still never been equaled, many imitators came and went, struggling with the crass intensity, but they were all failed attempts. Iggy made a point to declare conventionalism was out, and in its place — sleazy drug-fueled globs of noise. The Stooges remain one of my all-time favorite bands. And it has a lot to do with Raw Power. Some hipsters might declare, Raw Power, the weakest out of the holy trinity, due to its heavy praise, but there’s no denying its incendiary explosive strength. And on more than one occasion, I have been known to declare it my favorite album, ever. –Jason

Caetano Veloso “Caetano Veloso” (1971)

Ironically enough, Caetano Veloso’s almost entirely English language album is one of the most misunderstood of his classic 60s/70s period amongst English-speaking audiences (first place goes to Araca Azul, but that one at least gives you fair warning of its polarizability by the Caetano-in-bikini cover). Recorded while in exile in London, the album marks a dramatic musical departure from his first 2 solo outings that he would continue to explore up through 1977 or thereabouts. I must confess I don’t know too many details of Caetano’s (or Gilberto Gil’s) exile in London. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity on the part of the British, though there was probably no reason why anyone there should’ve known who he was. Apparently some Traffic members were big fans, and even helped out on Gil’s sessions but if I were George Harrison or Twink or Jimmy Page or Bill Wyman or Jack Bruce or Marc Bolan or Mike Heron and someone told me that the leading light of Brazil’s new underground rock movement was in my midst, I would totally be over there asking if he wanted to go bowling or split an appetizer or something. Or if I was Jimmy Page, I would ask if I could steal his guitar line from “Irene”.

Ironically enough, Caetano Veloso’s almost entirely English language album is one of the most misunderstood of his classic 60s/70s period amongst English-speaking audiences (first place goes to Araca Azul, but that one at least gives you fair warning of its polarizability by the Caetano-in-bikini cover). Recorded while in exile in London, the album marks a dramatic musical departure from his first 2 solo outings that he would continue to explore up through 1977 or thereabouts. I must confess I don’t know too many details of Caetano’s (or Gilberto Gil’s) exile in London. It seems like a bit of a missed opportunity on the part of the British, though there was probably no reason why anyone there should’ve known who he was. Apparently some Traffic members were big fans, and even helped out on Gil’s sessions but if I were George Harrison or Twink or Jimmy Page or Bill Wyman or Jack Bruce or Marc Bolan or Mike Heron and someone told me that the leading light of Brazil’s new underground rock movement was in my midst, I would totally be over there asking if he wanted to go bowling or split an appetizer or something. Or if I was Jimmy Page, I would ask if I could steal his guitar line from “Irene”.

One aspect of Veloso’s exile period is quite : he did NOT like it. The cover is amazing. Caetano looks like he’s 50, he’s cold, and you just told him a mildly offensive joke. One would assume this album is as bleak as Pink Moon but the first couple of songs might surprise you. “A Little More Blue” opens with a laidback, meandering acoustic figure that sounds a bit mellow but certainly not conducive to soul-bearing. The lyrics are about events that have made him sad, even though at the present moment “I feel a little more blue than then”. Along the way he peppers in references to his own exile and some truly vivid lyrics (“her dead mouth with red lipstick smiled”). An odd, dichotomous opener. “London, London” is for me the standout. And, oddly enough, it’s the jauntiest track, replete with playful flute like Donovan’s 67-era acoustic sides. It’s one of the most exquisitely beautiful songs I’ve ever heard concerning alienation, loneliness, and, above all, homesickness. In this respect, it can be seen as the post-traumatic counterpart to the desperate “Lost in the Paradise” from his previous album. And while I hold that song to be one of the best songs ever written, period, “London, London” offers the beautifully resigned flipside of that coin. And all this from a song whose refrain is “My eyes go looking for flying saucers in the skies”. Things start to get a bit darker with the more-produced “Maria Bethania”, a plea to his sister. “If You Hold a Stone” is an expanded, highly repetitve reworking of “Marinheiro So” from the previous album. I’m not going to pretend to know what he’s talking about here (even though it’s in English and he repeats it like 30 times) but I could listen to it all day long. The last song “Asa Branca” is the only Portuguese-language track on the album and as such it’s an emotionally powerful return to relatively familiar territory for Caetano. The song, written by Luiz Gonzaga and Humberto Teixeira, is about a native farmer (presumably) of Northeastern Brazil having to leave the land and his wife during one of the droughts that often occur in that part of the country because he is unable to make a living. At the end he promises to return. Amazingly, if you really try to live inside this album, you don’t really need to know Portugese to understand what this song is saying. A haunting, ethereal way to end perhaps the most personal album in Veloso’s storied career.

This album is notable for several reason. Firstly, it marks a dramatic change in musical direction for Veloso. I’ve never heard an album with a greater sense of space. There is a lot of silence on this album and it itself is utilized almost as an additional instrument, a “symphony of silence” (mental copyright) if you will. His first solo album was lush and sprightly and full of subtle sonic experimentation. His second album made the sonic experimentation much more explicit and combined this with a panoramic feeling that made that album at times feel tense and murky (not a bad thing in this case). This album does a dramatic about-face with its spare, acoustic lines, occasional bass-and-drum backing, and lyric-centric approach. This formula would reach full fruition on Transa and continue up until 1977’s African-influenced Bicho. The second notable aspect of this album is how well Veloso’s poetry translates into English. That’s no mean feat. Gil’s more awkward English makes his equivalent album difficult to decipher emotionally but Caetano’s only slightly accented English is perfectly suited to his prose that, though economical, are undeniably evocative and effective at relating emotional depth. Certainly not a place to start for Caetano Veloso, but you should try to find yourself here if you are willing to acquire more than 3 of his albums. –Mike

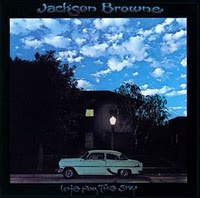

Jackson Browne “Late for the Sky” (1974)

One of those artifacts that sort of sum up the 1970s for me, along with the films Annie Hall, Nashville and Three Women. Like those movies, Late for the Sky deals with the aftermath of a romance in dreamy, almost surreal style. If you’re looking for rock, look elsewhere; but if you lean to the Nick Drake/Tim Buckley end of the singer-songwriter spectrum and you’ve been put off by Browne’s reputation for cloying navel-gazing, then put your prejudices aside and listen to this record. –Brad

One of those artifacts that sort of sum up the 1970s for me, along with the films Annie Hall, Nashville and Three Women. Like those movies, Late for the Sky deals with the aftermath of a romance in dreamy, almost surreal style. If you’re looking for rock, look elsewhere; but if you lean to the Nick Drake/Tim Buckley end of the singer-songwriter spectrum and you’ve been put off by Browne’s reputation for cloying navel-gazing, then put your prejudices aside and listen to this record. –Brad

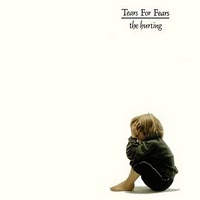

Tears For Fears “The Hurting” (1983)

Even though I was well past the teenage angst phase when The Hurting was released it still managed to strike a mighty big chord. If you thought that electronic pop was nothing more than lightweight froth, then this album will come as something of a shock. This is as close as music gets to defining the nightmare that is adolescence. It is amazingly depressing yet musically uplifting. The melancholic atmosphere is palpable especially on gruesome downer tracks like “Watch Me Bleed” and “Start Of The Breakdown” which are perfect fodder for manic-depressives. For my money this is the only Tears For Fears album worth owning. Here they revel in an unrefined talent combined with a pristine sound which would later be soiled by over production on the likes of Songs From The Big Chair. All the songs on The Hurting have been penned by Roland Orzabal and I read somewhere that the album is a reflection of his troubled childhood. So, while I could relate to this from a teenage perspective, Orzabal was suffering through this at a much younger age – which gives the album an even more harrowing edge. As he says “memories fade but the scars still linger”. –Ian

Even though I was well past the teenage angst phase when The Hurting was released it still managed to strike a mighty big chord. If you thought that electronic pop was nothing more than lightweight froth, then this album will come as something of a shock. This is as close as music gets to defining the nightmare that is adolescence. It is amazingly depressing yet musically uplifting. The melancholic atmosphere is palpable especially on gruesome downer tracks like “Watch Me Bleed” and “Start Of The Breakdown” which are perfect fodder for manic-depressives. For my money this is the only Tears For Fears album worth owning. Here they revel in an unrefined talent combined with a pristine sound which would later be soiled by over production on the likes of Songs From The Big Chair. All the songs on The Hurting have been penned by Roland Orzabal and I read somewhere that the album is a reflection of his troubled childhood. So, while I could relate to this from a teenage perspective, Orzabal was suffering through this at a much younger age – which gives the album an even more harrowing edge. As he says “memories fade but the scars still linger”. –Ian

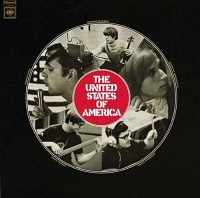

The United States of America (1968)

I first discovered this LP in a Capitol Hill thrift store in the mid-90’s, when it was still fairly easy to find such LP’s in thrift stores. Thumbing through the Broadway musical soundtracks and Herb Alpert LP’s, I came across a battered copy of this curiosity. Its cover suggested a bunch of M.I.T. graduate students performing research on how to be in a rock band, and the musical credits listed on the back were even more perplexing. The bassist played a fretless; there was no guitarist but there was an electric violin player. (And just what the hell was a “ring modulator” anyway?) I couldn’t tell how old the record was, but the hairstyles and packaging suggested about 1968 (I turned out to be right). The $3 sticker was enough incentive, so I bought it. Playing it when I got home, my reaction to its aural content was that of even more bafflement. It was a strange and shifting cacophony from start to finish: calliopes, pounding drums, tape loops, haunting ballads about clouds and deceased revolutionaries, Gregorian chants, chamber strings, Zappaesque satire, Salvation Army brass bands, and a barrage of otherworldly electronic bleeps and warbles. At first I wanted to throw it across the room, but within a few days it was all I was listening to and all I would listen to for the next month. We all know about these records, records that we happen upon by accident and which we initially don’t understand but which end up changing the very core of our being and defining our musical tastes. For these records, “love it or hate it” isn’t an apt descriptor. Like organ transplants, they are either violently rejected or they become a part of us. For me, The United States of America’s sole LP is one such record. –Richard

I first discovered this LP in a Capitol Hill thrift store in the mid-90’s, when it was still fairly easy to find such LP’s in thrift stores. Thumbing through the Broadway musical soundtracks and Herb Alpert LP’s, I came across a battered copy of this curiosity. Its cover suggested a bunch of M.I.T. graduate students performing research on how to be in a rock band, and the musical credits listed on the back were even more perplexing. The bassist played a fretless; there was no guitarist but there was an electric violin player. (And just what the hell was a “ring modulator” anyway?) I couldn’t tell how old the record was, but the hairstyles and packaging suggested about 1968 (I turned out to be right). The $3 sticker was enough incentive, so I bought it. Playing it when I got home, my reaction to its aural content was that of even more bafflement. It was a strange and shifting cacophony from start to finish: calliopes, pounding drums, tape loops, haunting ballads about clouds and deceased revolutionaries, Gregorian chants, chamber strings, Zappaesque satire, Salvation Army brass bands, and a barrage of otherworldly electronic bleeps and warbles. At first I wanted to throw it across the room, but within a few days it was all I was listening to and all I would listen to for the next month. We all know about these records, records that we happen upon by accident and which we initially don’t understand but which end up changing the very core of our being and defining our musical tastes. For these records, “love it or hate it” isn’t an apt descriptor. Like organ transplants, they are either violently rejected or they become a part of us. For me, The United States of America’s sole LP is one such record. –Richard

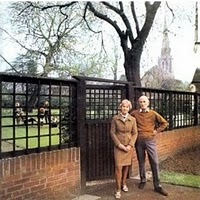

Fairport Convention “Unhalfbricking” (1969)

While Liege And Lief may very well be a more revolutionary and influential album than Unhalfbricking, I’m sure I’m not alone in thinking the latter even better than the former. As both their last album as “England’s Answer To Jefferson Airplane” and their first to move decisively towards traditional folk (and to feature Dave Swarbrick), it straddles both camps effortlessly. Of course both Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny contribute two excellent songs each, of which my favourite has always been the jazzy “Autopsy” (what a wonderful drummer Martin Lamble was!). Of course, “Who Knows Where The Time Goes” isn’t exactly a throwaway either. There’s no less than three Bob Dylan tracks, all of them unreleased by Bob in 1969, including the very moving “Percy’s Song”, featuring ex-Fairporter Ian Matthews on harmony vocals. (While this song had been recorded while he was still in the band, it began a tradition of ex-members making cameo appearances on new Fairport records that has made them see less like a band and more like a family.) The stunner, though, has to be the wonderful performance of the traditional song “A Sailor’s Life”, reputedly recorded in one take. I’ll take this one over all of Liege And Lief, thanks. Unlike some of Fairport’s other records, this one hasn’t aged a bit, and there’s absolutely no filler tracks. –Brad

While Liege And Lief may very well be a more revolutionary and influential album than Unhalfbricking, I’m sure I’m not alone in thinking the latter even better than the former. As both their last album as “England’s Answer To Jefferson Airplane” and their first to move decisively towards traditional folk (and to feature Dave Swarbrick), it straddles both camps effortlessly. Of course both Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny contribute two excellent songs each, of which my favourite has always been the jazzy “Autopsy” (what a wonderful drummer Martin Lamble was!). Of course, “Who Knows Where The Time Goes” isn’t exactly a throwaway either. There’s no less than three Bob Dylan tracks, all of them unreleased by Bob in 1969, including the very moving “Percy’s Song”, featuring ex-Fairporter Ian Matthews on harmony vocals. (While this song had been recorded while he was still in the band, it began a tradition of ex-members making cameo appearances on new Fairport records that has made them see less like a band and more like a family.) The stunner, though, has to be the wonderful performance of the traditional song “A Sailor’s Life”, reputedly recorded in one take. I’ll take this one over all of Liege And Lief, thanks. Unlike some of Fairport’s other records, this one hasn’t aged a bit, and there’s absolutely no filler tracks. –Brad