Melissa unleashed the dark majesty of Mercyful Fate on welcoming hordes of eager metalheads ready to set sail on a lake of fire, the band picking up where Priest left off with their late 70’s platters of pain and injecting an elevated sophistication and malevolence embodied in the angelic blasphemor wails of King Diamond. While the edge of Melissa’s sacrifical blade is slightly dulled by the tangled fortress “Satan’s Fall” on side two, the purity of purpose in classics like “Evil,” grave robbing “Curse of the Pharaohs,” and the pummeling “Black Funeral” let loose such torrents of spectral ferocity and hell-spawned riffage that Melissa stands as an all-consuming plethora of wicked delights. –Ben

Melissa unleashed the dark majesty of Mercyful Fate on welcoming hordes of eager metalheads ready to set sail on a lake of fire, the band picking up where Priest left off with their late 70’s platters of pain and injecting an elevated sophistication and malevolence embodied in the angelic blasphemor wails of King Diamond. While the edge of Melissa’s sacrifical blade is slightly dulled by the tangled fortress “Satan’s Fall” on side two, the purity of purpose in classics like “Evil,” grave robbing “Curse of the Pharaohs,” and the pummeling “Black Funeral” let loose such torrents of spectral ferocity and hell-spawned riffage that Melissa stands as an all-consuming plethora of wicked delights. –Ben

Jive Time Turntable

Ska and Reggae’s Missing Link:

A Guide to Rocksteady

Aside from reggae, ska was arguably Jamaica’s most important musical form, at least in terms of long-term cultural impact. Becoming ubiquitous all over the island at an astonishing speed in the early ’60s, ska grabbed hold of Jamaica’s musical consciousness like nothing had before. What’s more, despite its strange rhythms and heavily-Jamaican-accented vocals (when it wasn’t entirely instrumental), it crossed cultural boundaries almost effortlessly, making it catch on like mad in Britain and—to a lesser degree—the states.

Many Jamaican artists who eventually became international household names, among them Bob Marley and Jimmy Cliff, cut their teeth as performers during ska’s reign. In 1964, Millie Small scored an international smash hit with her skanked-up cover of “My Boy Lollipop”, and soon ska was everywhere. But by 1966, it was mysteriously vanishing in one place: Jamaica. A visit to a typical Kingston dance hall around that time would reveal that things were changing. Ska was becoming more melodic, more centered on the vocalist(s), and slower. Nobody knows for sure why this happened, but there are some theories. One suggests that during the summer of ’66, a brutal heatwave gripped Jamaica, forcing the musicians to slow things down on the dance floor so revelers wouldn’t collapse from heat exhaustion. Another postulates that the increasingly widespread availability of American soul records might have been a factor. (This would certainly make sense, as Stax and Motown influences can be heard all over the place on many Jamaican sides that were cut around this time.)

Whatever the cause, ska was metamorphosing into something completely different, so much so that it needed a new name; rocksteady seems to be the one that stuck. Rocksteady’s heyday was even more short-lived than its predecessor—-really only about two years-—and by the end of 1968, things were changing again. Recording technologies on the island were improving. Rastafarianism’s influence continued to spread, prompting a more socially conscious and politically-charged aesthetic. By the end of the decade, rocksteady was no longer, and reggae prevailed. But for many connoisseurs of modern Jamaican music, rocksteady represents its high point. It’s a form that’s rich and complex, yet raw, pure, and deeply soulful. It’s a truly unique product of its place and time, but one that transcends geography and culture, and which remains timeless. Here are five shining examples.

1. Prince Buster: Fabulous Greatest Hits (1980) – Though acquiring a popularity in the UK that at its peak rivaled the Beatles’s, Prince Buster never really established a large following in the US. Tracking down his one uneven RCA release from 1967 is a worthwhile endeavor, but this 1980 British comp is where all newcomers should start. All songs here were recorded in the mid to late ’60s, and many of them would serve as the blueprint for the 2 Tone movement that swept the UK a decade or so later.

1. Prince Buster: Fabulous Greatest Hits (1980) – Though acquiring a popularity in the UK that at its peak rivaled the Beatles’s, Prince Buster never really established a large following in the US. Tracking down his one uneven RCA release from 1967 is a worthwhile endeavor, but this 1980 British comp is where all newcomers should start. All songs here were recorded in the mid to late ’60s, and many of them would serve as the blueprint for the 2 Tone movement that swept the UK a decade or so later.

2. Desmond Dekker and the Aces Israelites (1969) “The Jamaican Smokey Robinson’s” single “Israelites” represents the only time when rocksteady cracked the US top 100. When it did, MCA rushed to cobble together this collection of songs, some of which by then were almost two years old. It’s still a fantastic showcase for some of Dekker’s best work. He’s at the top of his game here, and so is his backing band.

2. Desmond Dekker and the Aces Israelites (1969) “The Jamaican Smokey Robinson’s” single “Israelites” represents the only time when rocksteady cracked the US top 100. When it did, MCA rushed to cobble together this collection of songs, some of which by then were almost two years old. It’s still a fantastic showcase for some of Dekker’s best work. He’s at the top of his game here, and so is his backing band.

3. The Ethiopians Engine ’54: Let’s Ska and Rocksteady (1968) Rocksteady was the ideal vehicle for the vocal group, and as Jamaican vocal groups went, they didn’t get much better than the Ethiopians. Don’t let the “ska” in the title fool you; most of this is quintessential rocksteady, some of the best ever recorded.

3. The Ethiopians Engine ’54: Let’s Ska and Rocksteady (1968) Rocksteady was the ideal vehicle for the vocal group, and as Jamaican vocal groups went, they didn’t get much better than the Ethiopians. Don’t let the “ska” in the title fool you; most of this is quintessential rocksteady, some of the best ever recorded.

4. The Upsetters The Upsetter (1969) It’s difficult to figure out to whom this album should really be credited. One should know, however, that a young Lee “Scratch” Perry produced it, and whenever this eccentric mastermind is involved, things become, well… complicated. Featuring the work of a cadre of different musicians and vocalists, it’s a surprisingly cohesive late rocksteady record, one where the organ figures more prominently than the work of others at the time. It also hints at the dub revolution, of which Perry would be a prime architect a few years later.

4. The Upsetters The Upsetter (1969) It’s difficult to figure out to whom this album should really be credited. One should know, however, that a young Lee “Scratch” Perry produced it, and whenever this eccentric mastermind is involved, things become, well… complicated. Featuring the work of a cadre of different musicians and vocalists, it’s a surprisingly cohesive late rocksteady record, one where the organ figures more prominently than the work of others at the time. It also hints at the dub revolution, of which Perry would be a prime architect a few years later.

5. Various Artists Tighten Up: Volume 1 (1969) Music from Jamaica continued to capture the hearts and minds of young UK listeners in the late ’60s, but the record industry was slow to profit from its popularity. This Trojan Records “cash-in” comp. spawned a series that would become an institution and number well into the double digits before ending its run. Its first volume defined the musical tastes of the Skinhead movement (before it was co-opted by nationalist and racist thugs). Heavy on soul covers, a few of its tracks denote a distinct progression towards reggae, but most represent some last great moments from Rocksteady’s waning days.

5. Various Artists Tighten Up: Volume 1 (1969) Music from Jamaica continued to capture the hearts and minds of young UK listeners in the late ’60s, but the record industry was slow to profit from its popularity. This Trojan Records “cash-in” comp. spawned a series that would become an institution and number well into the double digits before ending its run. Its first volume defined the musical tastes of the Skinhead movement (before it was co-opted by nationalist and racist thugs). Heavy on soul covers, a few of its tracks denote a distinct progression towards reggae, but most represent some last great moments from Rocksteady’s waning days.

Further listening: Once the digging begins, one will be amazed by how so much great music came from such a small island in such a short period of time. The UK-based Trojan Records label remains the prime importer of rocksteady for a huge portion of the non-Jamaican world. The amount of compilations it has released over the years is overwhelming, but a good place to start is its budget-priced “threefer” box set series that it began churning out at the beginning of the 2000s. The Rocksteady Rarities and Skinhead comps are particular standouts, though there are plenty more (and some are available on vinyl). Also worth mentioning are Soul Jazz Records’ numerous comps that cover this period. Though they touch on other eras, 100% Dynamite and its many sequels and offshoots give a good overview of one of rocksteady’s most important producers, Sir Coxone Dodd. –Richard P

Are we forgetting your favorite rocksteady LP? We’d love to hear your comments:

Jive Time in Rolling Stone!

We were featured in Rolling Stone issue #308 as one of the Top 25 Record Stores in the USA, along with other Seattle shops Easy Street and Sonic Boom.

“Located in Seattle’s charming Fremont district, Jive Time is a modest-seeming local store whose holdings belie its size.” Read the entire article›

Winner: “Best Used Records”

Thank you Seattle! Jive Time Records won “Best Used Records” in the 2010 Seattle Weekly Best of Seattle.

Read the article›

Phil Manzanera/801 “801 Live” (1976)

Not your every day live album, 801 Live captures the supergroup featuring ex-Roxy Musicians Phil Manzanera and Brian Eno in one of their few performances. Featuring all the sonic detail, colorful guitar and synthesizer tones, and high-class musicianship you’d expect from such a lineup, another pleasant surprise here is the excellent recording, which almost sounds more like a studio album. A subtle, delicate style informs many of these performances, highlighting tracks from Eno and Manzanera’s early solo albums, the Quiet Sun album, and skewed reworkings of “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “You Really Got Me.” Brainy and electronic, but warm and human as well, 801 Live is an essential purchase for fans of the musicians involved, or seventies art-rock in general. –Ben

Not your every day live album, 801 Live captures the supergroup featuring ex-Roxy Musicians Phil Manzanera and Brian Eno in one of their few performances. Featuring all the sonic detail, colorful guitar and synthesizer tones, and high-class musicianship you’d expect from such a lineup, another pleasant surprise here is the excellent recording, which almost sounds more like a studio album. A subtle, delicate style informs many of these performances, highlighting tracks from Eno and Manzanera’s early solo albums, the Quiet Sun album, and skewed reworkings of “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “You Really Got Me.” Brainy and electronic, but warm and human as well, 801 Live is an essential purchase for fans of the musicians involved, or seventies art-rock in general. –Ben

Joni Mitchell “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” (1975)

And so, the dazzling beauty of Court and Spark carries on with The Hissing of Summer Lawns. Musically, it continues in a similar vein – an all-star lineup effortlessly shifting between Pop, Folk and Jazz, playing rich, multi-layered arrangements which never overpower Joni, whose main concern is always the song and its words. The lyrics have become more intimate, more melancholic on The Hissing of Summer Lawns and so has the music. Again, one or two songs don’t meet my undivided approval (Shadows and Light and The Jungle Line, even though the song marks the beginning of a lasting Pop format, the attempt to create a multicultural world music, ten years before Peter Gabriel, Sting and others), but the rest is again of celestial beauty. Even Joni, who would go on to record important albums until today, wasn’t able to match the artistic consistency and beauty of Court And Spark and The Hissing of Summer Lawns until many years later, with Turbulent Indigo and Travelogue. –Yofriend

And so, the dazzling beauty of Court and Spark carries on with The Hissing of Summer Lawns. Musically, it continues in a similar vein – an all-star lineup effortlessly shifting between Pop, Folk and Jazz, playing rich, multi-layered arrangements which never overpower Joni, whose main concern is always the song and its words. The lyrics have become more intimate, more melancholic on The Hissing of Summer Lawns and so has the music. Again, one or two songs don’t meet my undivided approval (Shadows and Light and The Jungle Line, even though the song marks the beginning of a lasting Pop format, the attempt to create a multicultural world music, ten years before Peter Gabriel, Sting and others), but the rest is again of celestial beauty. Even Joni, who would go on to record important albums until today, wasn’t able to match the artistic consistency and beauty of Court And Spark and The Hissing of Summer Lawns until many years later, with Turbulent Indigo and Travelogue. –Yofriend

The La’s “The La’s” (1990)

Even though John Power was an essential member of The La’s, I’m loathe to label the band the forerunner of Cast. There are some similarities in the homogeneous nature of the pop music but Power had little to do with writing anything for The La’s. The band was almost the private property of Lee Mavers who, if proof were needed of that fact, took it upon himself to destroy the only copy of the master tapes for the proposed second album because he was dissatisfied with the results. An action which ensured the self-destruction of the band. On the one hand the band’s demise was a cause for pity. The timeless nature of some of the songs, particularly “There She Goes”, hinted at them being around for some time to come. However, on the other hand, the perfectionist disposition of Mavers would probably result in interminable periods of time between albums during which the fickle music fan would have moved on to pastures new. Whilst the songs smack of a long Merseyside tradition for producing enduring pop, Mavers almost hypnotises the listener by repeating the same word or phonetic sounds throughout. The effect lulls you into a trance-like state and the music carries you with it. It really is quite an amazing album and one for which a follow-up would have been eagerly awaited. –Ian

Even though John Power was an essential member of The La’s, I’m loathe to label the band the forerunner of Cast. There are some similarities in the homogeneous nature of the pop music but Power had little to do with writing anything for The La’s. The band was almost the private property of Lee Mavers who, if proof were needed of that fact, took it upon himself to destroy the only copy of the master tapes for the proposed second album because he was dissatisfied with the results. An action which ensured the self-destruction of the band. On the one hand the band’s demise was a cause for pity. The timeless nature of some of the songs, particularly “There She Goes”, hinted at them being around for some time to come. However, on the other hand, the perfectionist disposition of Mavers would probably result in interminable periods of time between albums during which the fickle music fan would have moved on to pastures new. Whilst the songs smack of a long Merseyside tradition for producing enduring pop, Mavers almost hypnotises the listener by repeating the same word or phonetic sounds throughout. The effect lulls you into a trance-like state and the music carries you with it. It really is quite an amazing album and one for which a follow-up would have been eagerly awaited. –Ian

The Human League “Dare!” (1981)

When Ian Craig Marsh and Martyn Ware left the Human League following the release of the band’s second album “Travelogue”, one would have thought that the sole remaining member Philip Oakey would have either called it a day, or risked a solo career. When the music press revealed that he was re-assembling the new Human League with an unknown Bass player ( Ian Burden), a slide projector operator (Philip Adrian Wright), two girls he had met in Sheffield club with no musical experience whatsoever (Joanne Catherall and Susanne Sulley), and a guitarist from the long defunct Punk band The Rezillos (Jo Callis), many must have thought that Oakey had lost the plot, and the world was half expecting the next appointment to ba a fire eating lion tamer from Halifax. Virgin uneasily supported Oakey’s moves and recording started on the band’s 3rd album “Dare”, with The Stranglers producer Martin Rushent at the helm. Musically, Oakey wanted to retain the mechanical, industrial synthesised instrumentation and style, but introduce a Pop and Dance element to make the music a more viable proposition to the growing New Romantic following. He suceeds, and “Dare” is THE best Pop/Synth/New Romantic album of the era, a culmination of great Pop songs, dark vocals, and simple, crisp instrumentation, resulting in a number one album in the U.K. and a top 5 success in the States. There are many highlights, from the pure Pop duets “Don’t You Want Me” and “Open Your Heart”, the brilliant Dance numbers “Sound Of The Crowd” and “Love Action”, the upbeat “Things That Dreams Are Made Of”, and the paranoic “Darkness”. A masterpiece of it’s time, and Oakey would never be able to recapture this moment again. The album gave us an excitement that no one had come close to. –Ben H

When Ian Craig Marsh and Martyn Ware left the Human League following the release of the band’s second album “Travelogue”, one would have thought that the sole remaining member Philip Oakey would have either called it a day, or risked a solo career. When the music press revealed that he was re-assembling the new Human League with an unknown Bass player ( Ian Burden), a slide projector operator (Philip Adrian Wright), two girls he had met in Sheffield club with no musical experience whatsoever (Joanne Catherall and Susanne Sulley), and a guitarist from the long defunct Punk band The Rezillos (Jo Callis), many must have thought that Oakey had lost the plot, and the world was half expecting the next appointment to ba a fire eating lion tamer from Halifax. Virgin uneasily supported Oakey’s moves and recording started on the band’s 3rd album “Dare”, with The Stranglers producer Martin Rushent at the helm. Musically, Oakey wanted to retain the mechanical, industrial synthesised instrumentation and style, but introduce a Pop and Dance element to make the music a more viable proposition to the growing New Romantic following. He suceeds, and “Dare” is THE best Pop/Synth/New Romantic album of the era, a culmination of great Pop songs, dark vocals, and simple, crisp instrumentation, resulting in a number one album in the U.K. and a top 5 success in the States. There are many highlights, from the pure Pop duets “Don’t You Want Me” and “Open Your Heart”, the brilliant Dance numbers “Sound Of The Crowd” and “Love Action”, the upbeat “Things That Dreams Are Made Of”, and the paranoic “Darkness”. A masterpiece of it’s time, and Oakey would never be able to recapture this moment again. The album gave us an excitement that no one had come close to. –Ben H

Parliament “Funkentelechy vs. the Placebo Syndrome” (1977)

George Clinton was unstoppable. The previous album The Clones Of Dr. Funkenstein was good, but this LP is unbelievable. Bob Gun opens the album with danceable Funk. Then, Sir Nose d’Voidoffunk: aside from being ultra-funky and the “lyrics” mad beyond control, the music here may be the most advanced and far-reaching of all Parliament tracks. Just listen to Bernie Worrell’s synth wizardry and his abstract comments on the acoustic piano, Clinton’s Sir Nose travesty, the girls’ background vocals, the brass arrangement, the fat bass – at a running time of more than ten minutes, this song is a miracle! Other highlights: Funkentelechy (also over ten minutes long) and the hit, Flash Light . –Yofriend

George Clinton was unstoppable. The previous album The Clones Of Dr. Funkenstein was good, but this LP is unbelievable. Bob Gun opens the album with danceable Funk. Then, Sir Nose d’Voidoffunk: aside from being ultra-funky and the “lyrics” mad beyond control, the music here may be the most advanced and far-reaching of all Parliament tracks. Just listen to Bernie Worrell’s synth wizardry and his abstract comments on the acoustic piano, Clinton’s Sir Nose travesty, the girls’ background vocals, the brass arrangement, the fat bass – at a running time of more than ten minutes, this song is a miracle! Other highlights: Funkentelechy (also over ten minutes long) and the hit, Flash Light . –Yofriend

The Velvet Underground “1969: The Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed” (1974)

“Good evening, we’re the Velvet Underground…” It’s a far cry from another intro uttered that same year: “Ladies and gentleman, the greatest rock and roll band in the world…” Lou Reed’s intro is obviously more understated and, coming from a notoriously prickly New Yorker, surprisingly cordial. And it goes on for awhile… After asking the audience if they would prefer a one-long-set or two-set performance, we get a recap of a Dallas Cowboys game. Almost a full minute and a half has passed when, out of nowhere, Reed casually states, “This is a song called I’m Waiting for My Man”. The band then wastes no time locking into an historic, rock-solid groove.

“Good evening, we’re the Velvet Underground…” It’s a far cry from another intro uttered that same year: “Ladies and gentleman, the greatest rock and roll band in the world…” Lou Reed’s intro is obviously more understated and, coming from a notoriously prickly New Yorker, surprisingly cordial. And it goes on for awhile… After asking the audience if they would prefer a one-long-set or two-set performance, we get a recap of a Dallas Cowboys game. Almost a full minute and a half has passed when, out of nowhere, Reed casually states, “This is a song called I’m Waiting for My Man”. The band then wastes no time locking into an historic, rock-solid groove.

1969: The Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed has always been a VU fan favorite, but it’s overshadowed by the band’s iconic studio catalog. Misguided marketing and lame packaging are also to blame for its somewhat limited cult status. Released in 1974, during the most lucrative period of Lou Reed’s solo career, Mercury’s insistence on using his name in the title implied that other members of the VU were little more than his backing band, which couldn’t be further from the truth. The inner gatefold spread is also misleading, depicting an earlier and different (in both sound and appearance) incarnation of the band. Finally there’s the cover itself, which, in the immortal words of Patti Smith, “eats shit”. Despite this indifferent misrepresentation, this record is the first and last word in any discussion about the Velvet Underground as a live act. Almost all of the band’s classics are here, given new life—sometimes even bettered—by Reed’s remarkably expressive vocals (one pines for the days when he actually sang), Sterling Morrison’s precision guitar work, Mo Tucker’s majestically simplistic drumming, and the melodic bass-playing of the most under-appreciated VU member, Doug Yule. Surprisingly large amounts of live VU performances were recorded, but this collection—the bulk of which was culled from a multi-night engagement at a tiny club in Dallas—has the best sound quality of any that have survived. It’s a different sound than the sharp and crackly production of the 1967 “Banana” LP: bluesier, and with a bottom that rattles the windows and shakes the floors. It’s the sound of a band that’s been honing its craft in divey clubs and ballrooms across the US for over a year, and which, during the last few months of the ’60s, delivers the best live rock and roll show on either side of the Mississippi. –Richard P

XTC “English Settlement” (1982)

What on earth was I thinking of? After English Settlement I gave up on XTC for 20 years! There’s simply no excuse. I knew the first time I heard English Settlement I was listening to a classic and yet I still let my interest lapse. This is probably one of the most perfectly crafted double albums by any English band, notwithstanding Exile On Main Street and London Calling. It contains such complex, intricate constructions the word “song” seems too restrictive a word to describe their function. Like an absorbing novel, a spectacular movie or a sumptuous meal, this album can be enjoyed on many levels. There was an abridged version of English Settlement released at the same time as this double and I’m aware that many prefer it, feeling it cuts out the filler. I’ve never heard it and I never want to. Listening to English Settlement today, I can’t think of a single track I’d want to get rid of. It would be like choosing a favourite from among my kids.

What on earth was I thinking of? After English Settlement I gave up on XTC for 20 years! There’s simply no excuse. I knew the first time I heard English Settlement I was listening to a classic and yet I still let my interest lapse. This is probably one of the most perfectly crafted double albums by any English band, notwithstanding Exile On Main Street and London Calling. It contains such complex, intricate constructions the word “song” seems too restrictive a word to describe their function. Like an absorbing novel, a spectacular movie or a sumptuous meal, this album can be enjoyed on many levels. There was an abridged version of English Settlement released at the same time as this double and I’m aware that many prefer it, feeling it cuts out the filler. I’ve never heard it and I never want to. Listening to English Settlement today, I can’t think of a single track I’d want to get rid of. It would be like choosing a favourite from among my kids.

Considering how perfect this album is I’ve always felt that it was around the release of English Settlement that it all started going wrong for XTC. An overstressed and exhausted Andy Partridge was overtaken by stage-fright and suffered a breakdown soon after the album’s release. As a result the album passed relatively unnoticed. How huge could this band have been if given the opportunity to publicise and tour English Settlement? How huge could this band have been if Partridge had ever been able to overcome his fear? Tragic really.

Even though Colin Moulding contributes the ska rhythms of “English Roundabout”, the twisted “Fly On The Wall” and the excellent “Ball And Chain”, English Settlement really is Partridge’s album. “Senses Working Overtime” would provide the band with their only top ten single. “All Of A Sudden (It’s Too Late)” is simply sublime. “Yacht Dance” is a mix of pure pop and English folk and Dave Gregory’s Spanish guitar is a revelation and the flamenco rhythms continue to ripple through anti-gun rant “Melt The Guns”. “It’s Nearly Africa” brings the sounds of that continent into XTC’s quaintly weird world and “Snowman” takes what is well-worn subject matter for a song – a crumbling relationship – and comes at it from an unusual perspective.

English Settlement is a fabulous album but, amazingly, still isn’t the high point for XTC but, as an example of the quintessential English band playing the quintessential English eccentrics, it’s difficult to beat. –Ian

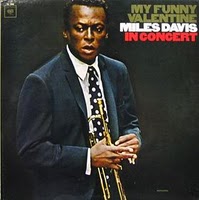

Miles Davis “My Funny Valentine” (1965)

Never has there been such a perfect example of the difference between what we might call the Apollonian and Dionysian (if we were utterly pretentious). In February 1964, Miles Davis and his then band — Tony Williams on drums, Ron Carter on bass, Herbie Hancock on piano and George Coleman on sax — played a concert at New York’s Philharmonic Hall that was subsequently split for release on two LPs. The fast numbers went on Four and More, a fun little album but no great shakes; there’s plenty of power, but not much else. The ballads, though, wound up here, and the end result is one of the most beautiful and moving jazz records I own. It’s stunningly delicate; the five musicians play with almost ESP-like sensitivity to each other. Listen, though, to Miles; he has rarely played with such lyricism, such emotion. “Stella by Starlight” in particular sounds like a direct connection to a place far deeper than any he has gone before. Naked, and necessary. –Brad

Never has there been such a perfect example of the difference between what we might call the Apollonian and Dionysian (if we were utterly pretentious). In February 1964, Miles Davis and his then band — Tony Williams on drums, Ron Carter on bass, Herbie Hancock on piano and George Coleman on sax — played a concert at New York’s Philharmonic Hall that was subsequently split for release on two LPs. The fast numbers went on Four and More, a fun little album but no great shakes; there’s plenty of power, but not much else. The ballads, though, wound up here, and the end result is one of the most beautiful and moving jazz records I own. It’s stunningly delicate; the five musicians play with almost ESP-like sensitivity to each other. Listen, though, to Miles; he has rarely played with such lyricism, such emotion. “Stella by Starlight” in particular sounds like a direct connection to a place far deeper than any he has gone before. Naked, and necessary. –Brad