Up to a point, there is no faulting the genius of the Damned, and Machine Gun Etiquette is the culmination of their (r)evolution. A debatable point, of course, as their Damned Damned Damned album could be considered their first, last AND greatest… BUT, Machine Gun finds the band expanding their cheeky short-loud-fast into something… well, grander! They expanded their song writing beyond what, at the time, had already become cliché 1-2-3-4 punk rock. Perhaps it was Captain Sensible’s (melodic) move to guitar? Maybe they were just getting (ahem) older? I don’t know for sure, but tracks like Plan 9 Channel 7, Love Song…even the faultless cover of MC5’s Looking At You, were some of the first punk songs I could call…(don’t laugh) beautiful! And the songs still hold up, I can put this on anytime and it makes me really happy. –Nipper

Up to a point, there is no faulting the genius of the Damned, and Machine Gun Etiquette is the culmination of their (r)evolution. A debatable point, of course, as their Damned Damned Damned album could be considered their first, last AND greatest… BUT, Machine Gun finds the band expanding their cheeky short-loud-fast into something… well, grander! They expanded their song writing beyond what, at the time, had already become cliché 1-2-3-4 punk rock. Perhaps it was Captain Sensible’s (melodic) move to guitar? Maybe they were just getting (ahem) older? I don’t know for sure, but tracks like Plan 9 Channel 7, Love Song…even the faultless cover of MC5’s Looking At You, were some of the first punk songs I could call…(don’t laugh) beautiful! And the songs still hold up, I can put this on anytime and it makes me really happy. –Nipper

Album Reviews

Thelonious Monk “Brilliant Corners” (1957)

With four of the five selections here being originals, Brilliant Corners displays the pianist’s obsession with knotty, jagged melodies that leap around in unpredictable ways, be it on the segmented, abrasive title track, the obviously bluesy “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” the ragged ballad “Pannonica,” which features Monk simultaneously playing a bell-like celeste and piano, and the bold bounce of “Bemsha Swing.” The sidemen, including Sonny Rollins, settle in to the compositions admirably, taking inspiration from Monk’s idiosyncratic approach, and there’s a sense of freedom in their solos despite the songs’ atypical nature. A great example of one of the most original voices in classic jazz. –Ben

With four of the five selections here being originals, Brilliant Corners displays the pianist’s obsession with knotty, jagged melodies that leap around in unpredictable ways, be it on the segmented, abrasive title track, the obviously bluesy “Ba-Lue Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are,” the ragged ballad “Pannonica,” which features Monk simultaneously playing a bell-like celeste and piano, and the bold bounce of “Bemsha Swing.” The sidemen, including Sonny Rollins, settle in to the compositions admirably, taking inspiration from Monk’s idiosyncratic approach, and there’s a sense of freedom in their solos despite the songs’ atypical nature. A great example of one of the most original voices in classic jazz. –Ben

Pink Floyd “Ummagumma” (1969)

A double album of sustained unsettling bizarreness that manages to outdo most psychedelia by building it up in a live setting and tearing it down in the studio, this is arguably Pink Floyd at their rawest: one part live freak-out, one part studio freak-out. It prefigures much of what we’ve come to know and love by way of so-called krautrock: the incorporation of avant-garde forms into the rock format. Somebody had to do this sort of thing, no? And they get points for sheer nerve. Still, I’m not sure how many normal people can actually sit through this from start to finish. Listeners who appreciate avant-garde music will likely find this crude and boring, while people who cling to song-form and melody will likely find this alienating and boring. Let’s try to straddle the fence and hear this as a far-reaching rock record, which it is.

The live album is primo psychedelic freak-out stuff, with a rendition of “Careful With That Axe, Eugene” that surpasses the studio version by eight miles, and three other tracks from their first two albums: “Astronomy Domine” is more abstract than its Barrett incarnation and a refreshing variation that exposes its eerier side; while the two from A Saucerful of Secrets make up for the lack of intricate production flourishes by forging a new frontier in spaced-out noise. All four renditions are exceptional, and this is a classic live album, never mind the minor quibbles about sound quality.

The studio album is a little tougher to take, with four “suites,” each one contributed by one band member. It’s an impressive studio achievement and certainly a left-field rock experiment: psychedelic freak-out stuff with a more intellectual bent—meaning it’s not as interesting as the live album—though I’m sure it blew minds at the time of release. Richard Wright’s portion includes prepared piano and faux-free jazz and some moody mellotron parts complemented by chirping birds. It’s not bad. Roger Waters’ two contributions include a lengthy psych-folk ditty (with touches of Donovan) complemented by chirping birds and a babbling brook … and secondly a lengthy psych-folk rave-up that, as its title quite explicitly denotes, consists of nothing but human-simulated/studio-manipulated faux-rodent noises and an imitation of a drunken Scotsman. These are also not bad. David Gilmour’s piece is the most accessible, a suite that anticipates Meddle’s drifting atmosphere and even becomes songlike towards the end, with hints of King Crimson’s contemporaneous output. It’s probably the closest thing to the classic Floyd sound, and might appeal most to their rabid fans. Nick Mason’s percussion experiment is a kind of musique concrete for beginners, a mildly interesting tape-manipulated mood piece that wouldn’t be out of place as the soundtrack to some late-60s high school documentary about physics; it opens with a flute theme and slowly builds to a drum solo and then a multi-tracked drum duet before devolving back to its flute theme … it seems a little quaint nowadays but fits this lengthy record’s creepy vibe. And it’s not really bad, either.

All told, a much better album than it should be: a mindfuck for people who aren’t predisposed to having their minds frequently fucked, and definitely not among Floyd’s weakest releases…. Make of that what thou wilt. —Will

Public Enemy “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back” (1988)

There’s a reason why this album is consistently listed near the top of any list of great albums, hip-hop or otherwise. The layered production and album’s thematic cohesion represented a quantum leap over anything that had been released in hip-hop to that point. Yet, it doesn’t sound the slightest bit dated (like, for example The Chronic) because no one was able to emulate the Bomb Squad’s sound the way that G-Funk or RZA-style production were constantly bitten years later. The result is an album that was monumentally important at the time of its release, and still just as fresh and jaw-dropping nearly 20 years later.

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back is the definitive group statement from one of hip-hop’s greatest acts. Chuck D is a true force on the mic, but PE doesn’t get by on his skills alone, though they certainly could. Despite rhymes that convey his considerable intelligence, he has a presence on the microphone that has rarely been matched. Even if he wasted his flows on cookie-cutter battle raps, he could do so convincingly. Fortunately for us, that isn’t the case. Flava Flav, far from the caricature he is now, provides the perfect foil for Chuck. Abrasive and wild, he underscores all of Chuck D’s statements like an exclamation point. Meanwhile, Terminator X and the Bomb Squad propel the backing tracks into the stratosphere with a constant barrage of samples, scratches and funky beats. Constantly self-referencing, the music here is dense and complex, adding to the epic feel of the album (though it runs just under an hour). Not to mention, they have the best song titles in all of music: “Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos”, “Terminator X on the Edge of Panic”, etc.

I am usually a little wary of artists that are this overtly political, and I always thought that Ice Cube traveled too far down that road, for example. With PE, however, the politics only add to the urgency of the album. It doesn’t hurt that Chuck D is typically right on with his lyrics. It also doesn’t hurt that all of the themes touched on (drugs, war, police, the justice system, etc.) are always relevant.

To say that It Takes a Nation… is a good rap album with a couple of classic tracks would be a gross understatement of this album’s value. This is a masterwork, and nearly every other track has become a standard (“Rebel w/out a Pause”, “Bring the Noise”, “Night of the Living Baseheads”, “Don’t Believe the Hype”, “She Watch Channel Zero?!”…). No filler. The consistency is staggering. In fact, at first listen, the record can be a little intimidating, since there aren’t any concessions made in the effort to vary their output or spawn a hit single. Chuck D even anticipates that they won’t have commercial success in his line: “Radio stations/I question their blackness/They call themselves black/But we’ll see if they’ll play this.” Multiple listens reveal more and more of what Public Enemy has embedded into this startling effort. Any fan of hip-hop who doesn’t own this album needs to. As does any fan of music who has dismissed hip-hop as anything less than a vibrant art form. —Lucus

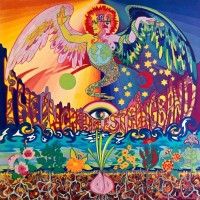

Incredible String Band “The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion” (1967)

The second ISB album, regarded by many as a peak moment in the evolution of the British psychedelic underground. Following the release of the band’s trio debut in the summer of 1966, Clive Palmer had split for Afghanistan, Robin Williamson had taken his girlfriend, Licorice McKechnie, to Morocco for an open-ended stay, and Mike Heron had opted to stay in Edinburgh. Heron returned to playing rock music, but in late 1966, Williamson came back from Marrakesh, bearing a wealth of strange North African musical instruments, and an equal number of compositional ideas.

Before long, the two had reformed the ISB as a duo, and they soon began woodshedding in a rural Scottish cottage. Joe Boyd, who had produced the first LP, had started a new club in London called the UFO, in partnership with John “Hoppy” Hopkins (the founder of The International Times). Boyd felt the scene was boiling over and was convinced the ISB had their part to play. He visited the pair, suggesting he become their manager and that they record a second album. The sessions for The 5000 Spirits Or The Layers Of The Onion happened at John Wood’s London studio in late spring 1967, and featured the lovely bass work of Danny Thompson (who had joined Pentangle two months earlier), the vocals of Licorice, and guest spots for “Hoppy”’s piano and Nazir Jairazbhoy’s sitar.

The album was released to great fanfare in July, 1967, just as the ISB was returning from an appearance at the Newport Folk Festival. With its uber-psych cover art by Dutch design firm The Fool (then being envied for their work with The Beatles), and classic songs (traditional folk, swathed in kaftans, incense and finger cymbals), 5000 Layers was truly a record for its time. Hailed by everyone from John Peel to Paul McCartney, the album went to Number One on the UK folk charts, and was an omnipresent accessory in every student garret. Four-plus decades on, it remains one of the all-time readymade classics of the ‘60s. —Forced Exposure

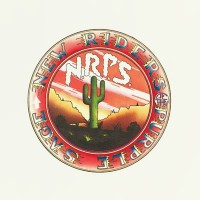

New Riders of the Purple Sage (1971)

New Riders of the Purple Sage is a strong debut, notable not only for the involvement of the legendary Jerry Garcia as pedal steel guitarist, but also for the great singing from John Dawson, the strong harmonies, David Nelson’s pickin’, and, perhaps most importantly, the catchy strong writing — there isn’t a weak song in the bunch.

Solidly in the county rock vein, this album is a whole different animal from Garcia’s work as a guitarist with the Grateful Dead or as a banjo player with Old and in the Way, so direct comparisons are difficult. Sure, the Dead played plenty of country material on American Beauty and Workingman’s Dead, but this does not sound like either of those albums, nor does it evoke the Byrds’ brand of country rock; it’s more akin to the Stones’ “Dead Flowers” (with which, appropriately enough, the current lineup of NRPS has opened many shows since their debut in 2006). I have heard their style called cosmic country, which would seem to fit in reference to the “far out” pedal steel style of both of the band’s prominent pedal steel guitarists, so it seems as good of a label as any.

Those who enjoy the mournful qualities of Jerry Garcia’s voice probably will enjoy John “Marmaduke” Dawson’s lead vocals here, and a listener’s reaction to the lead-off track, “I Don’t Know You”, will probably serve as a pretty good indicator as to whether or not they will like the rest of the album. “I Don’t Know You” features some fun interaction between Garcia and Nelson, and any fears that these tunes will be stretched beyond the boundaries of good taste are allayed by its radio-friendly brevity of two-and-a-half minutes.

Those of us who happen to enjoy the Grateful Dead’s explorations only get one song substantially longer than five minutes on the entire album, so, again, although listeners may find some vocal, tonal, and instrumental common ground, this album does not sound like anything that the Grateful Dead have ever done. The one song where they do stretch out is the laid back “Dirty Business”, and we get to hear some raunchy pedal steel from Garcia there, just enough to satisfy my appetite for it. Other tunes, in particular “Henry”, “Louisiana Lady”, and “Glendale Train”, are such tight, fun singalongs that stretching them out with long jams would have seemed superfluous in this studio setting.

It’s great that Jerry hooked up with his longtime buddy David Nelson and the rest of the band to get this thing rolling with such a fine album, because, even after Jerry left this band to be replaced by the amazing Buddy Cage, the group played many great shows and recorded some strong tunes. I love this band, and, even with a slew of country rock and alt country bands cropping up over the years, to my awareness, none of them have ever really mined this same vein. —Len

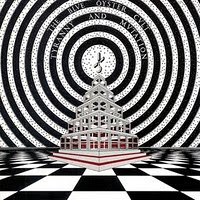

Blue Öyster Cult “Tyranny and Mutation” (1973)

With considerably more vivid production and a greater focus on riff and rhythm than on atmosphere—and even more cryptic lyrics—the second BOC LP is superior to their debut by a dark country mile. The self-mythologizing continues, even picking up where the first record left off, with a revisitation of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police as some kind of secret Fascist society on the ferocious garage-burner “The Red & the Black.” The decadence and debauchery that threaded through their eponymous is in even stronger evidence here, too, with tracks such as the bluesy “O.D.’d on Life Itself” and the fiery proto-punk of “Hot Rails to Hell,” which anticipates bands like the Damned (albeit with the screwed-down-tight musicianship that make BOC’s early records such a treat and the contemporaneous live shows legendary). The album gets stranger as it progresses, with talk of Diz Busters, a Baby Ice Dog, and one of the band’s most bizarre creations, that Mistress of the Salmon Salt, who, moreover, is a Quicklime Girl. Zany might be the best word to describe the content here: they were often referred to as the “American Black Sabbath,” but the appellation only fits to the extent that BOC are similarly dark in their themes and can bring the Heavy when it’s called for: otherwise, these guys are punkier (Patti Smith was a close connection and occasional co-writer at the time), at once more traditionalist and more experimental (think the chug-chugging of the incipient Detroit punk scene crossed with the theatrical arrangements of Killer-era Alice Cooper and you’re on the right track), and a whole lot funnier than Birmingham’s doom purveyors. –Will

With considerably more vivid production and a greater focus on riff and rhythm than on atmosphere—and even more cryptic lyrics—the second BOC LP is superior to their debut by a dark country mile. The self-mythologizing continues, even picking up where the first record left off, with a revisitation of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police as some kind of secret Fascist society on the ferocious garage-burner “The Red & the Black.” The decadence and debauchery that threaded through their eponymous is in even stronger evidence here, too, with tracks such as the bluesy “O.D.’d on Life Itself” and the fiery proto-punk of “Hot Rails to Hell,” which anticipates bands like the Damned (albeit with the screwed-down-tight musicianship that make BOC’s early records such a treat and the contemporaneous live shows legendary). The album gets stranger as it progresses, with talk of Diz Busters, a Baby Ice Dog, and one of the band’s most bizarre creations, that Mistress of the Salmon Salt, who, moreover, is a Quicklime Girl. Zany might be the best word to describe the content here: they were often referred to as the “American Black Sabbath,” but the appellation only fits to the extent that BOC are similarly dark in their themes and can bring the Heavy when it’s called for: otherwise, these guys are punkier (Patti Smith was a close connection and occasional co-writer at the time), at once more traditionalist and more experimental (think the chug-chugging of the incipient Detroit punk scene crossed with the theatrical arrangements of Killer-era Alice Cooper and you’re on the right track), and a whole lot funnier than Birmingham’s doom purveyors. –Will

The Gun Club “Fire of Love” (1981)

More than any other white musicians in the latter half of the 20th century, the Gun Club embodied the true spirit of American blues music. Members of the musical intelligentsia like to point to 1960s as a period of revitalization for the blues, the decade in which major British Invasion rock groups like Cream and the Stones, having cut their teeth on the recordings of Robert Johnson and Skip James, paid tribute to their idols and introduced the quintessentially American art form to a new generation of enthusiastic young fans. In reality, however, the true legacy of the ’60s Brits, however great their music and sincere their adoration may have been, was to sanitize and whiten the blues, to minimize the ragged starkness and raw emotion and instead to emphasize technical proficiency and a sense professionalism that bordered on sterility (in the process giving rise to flashy guitar-wizardry-as-blues, exemplified by the likes of Robert Cray and Stevie Ray Vaughan). The result was a product more commercially accessible to the record-buying public (mostly white teenagers), but it was drained of the visceral power that had made the blues such an authentic and enduring form of cultural expression.

Ironically enough, it took the Gun Club, a bunch of white California punks, to recapture some of that lost essence. Coalescing in 1980 around lead vocalist and songwriter Jeffrey Lee Pierce, the Gun Club were, along with bands like X and the Flesh Eaters, a staple of the Los Angeles punk movement, a regional music scene that spawned some of the most intriguing, enigmatic, and downright weird music of punk’s golden age–stuff so garish and surreal it could only have come out of Hollywood. And the Gun Club were perhaps the greatest and weirdest of them all.

On their 1981 debut Fire of Love, Pierce and company strip away the veneer of politeness that had infected the blues since the ’60s and restore the raw intensity that one finds in the recordings of early country blues artists, demonstrating themselves to be the real heirs of the blues legacy that Eric Clapton and other polished veterans of the British Invasion tried to claim for themselves. Most music writers point out that the Gun Club were among the first groups to combine punk with blues, but such a simplistic description does the band a grave disservice. Incorporating punk, noisy garage rock, swampy Delta blues, and even gothic country and rockabilly, the Gun Club crafted a sound that is completely unique and almost impossible to describe. Though music writer Denise Sullivan takes an admirable stab at it by coining the phrase “tribal psychobilly blues,” even this fails to do justice to the band’s threatening swagger, to Jeffrey Lee Pierce’s sinister, demonic howls, and to the eerie, unsettling voodoo rhythms that throb and pulse like blood pounding deafeningly in your ears.

Pierce, whose depraved poeticism and shamanistic persona draw inevitable comparisons to the Lizard King himself, fully embraced the macabre subject matter so pervasive in early blues music–mysticism, murder, violence, and the occult–and penned some of the most startling, imaginative, and nightmarishly surreal lyrics in all of rock music. Every song on this album is outstanding, from the perverse country bounce of “Sex Beat,” the terrifying murder-sex ballad “Jack on Fire,” and the explosive punk assault of “She’s Like Heroin to Me,” to the frenetic energy of “For the Love of Ivy” (the album’s magnum opus) and the slashing slide guitar of “Preaching the Blues,” one of the most inspired reinterpretations of a Robert Johnson tune that I’ve ever heard.

Jack White hit the nail on the head when he claimed that Fire of Love should be “taught in schools.” Nothing before or since has ever sounded like this. Fire of Love is one of the greatest albums ever, a collection of recordings that sounds simultaneously fresh and timeless, that stands alone as a uniquely visionary work and also fits effortlessly into the populist tradition of American roots music. If the great Skip James had fronted a garage rock band before he died, I have a feeling that it would’ve sounded something like this. —Adam

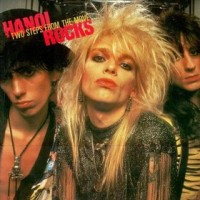

Hanoi Rocks “Two Steps From the Move” (1984)

Legendary glam rockers who originated in Finland and took the Sunset Strip scene by storm with this, their sixth album overall and first on a major worldwide label. Sadly it was the last album for drummer Razzle, who was famously killed in a car crash in which Motley Crue’s Vince Neil was driving. By 1985 the Rocks had split, but they came back a few years ago to tour and record again. This album showcases a band that were true pioneers of the LA hard rock sound, inspiring the likes of LA Guns and GNR.

Highly recommended! —Fletchanator

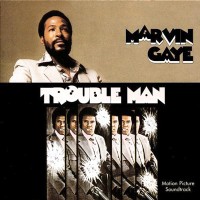

Marvin Gaye “Trouble Man” (1972)

The title track is reason enough to own this great LP. It’s a jazzy, strutting, ethereal masterpiece of music that hasn’t aged a day in 40 years (don’t those cymbals and echoing snare-drum wafting in over the piano on the intro just give you the chills?) and stands as a major landmark in both movie music and the career of Marvin Gaye.

The rest of this soundtrack is just that, beautiful ‘sound’. The instrumentals that comprise this collection incorporate elements of jazz, soul, classical and pop, to stunning effect. While the movie itself hasn’t exactly endured very well, the accompanying music is timeless. Mr. Gaye had yet another classic on his hands. —Willie

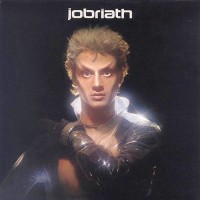

Jobriath “Creatures of the Street” (1974)

Jobriath’s self-titled 1973 debut received positive notices, but the ensuing publicity hype all but sunk the artist’s critical reputation. He’d delivered the musical goods, but his manager’s hype machine and a failed-to-materialized grand tour of European opera houses hung over this follow-up like a rain cloud. The notoriety that greeted the first openly gay rock star’s debut had turned to scorn and apathy, resulting in little notice of a sophomore album that featured some wonderfully crafted, dramatic glam-rock. It probably didn’t help that Jobriath’s manager stuck his name in the credits as “Jerry Brandt Presents Jobraith in Creatures of the Street,” and suggested the album was a romantic comedy.

Co-producing once more with engineer Eddie Kramer, Jobriath’s second album’s broadens his reach with additional orchestrations and showy production touches. He continues to sing in a high register, retaining a tonal resemblance to Mick Jagger and Mott the Hoople’s Ian Hunter, but here he adds gospel and classical elements to both the vocal arrangements and his piano playing. Despite suggestions that this was a concept album, the concept remains obscure. Still, much of the album sounds as if it were a cast album to a stage musical with rock-opera pretensions. “Street Corner Love” is rendered as mannered show rock, and the stagey “Dietrich/Fondyke” combines a full orchestral arrangement, piano flourishes and a female chorus into a dramatic splash of film nostalgia. The funky “Good Times” sounds as if its tribal-rock vibe was lifted from “Hair” – a period play in which Jobriath had performed a few years earlier.

More inventively, the grittily-titled “Scumbag” is rendered as the sort of music hall country-folk the Kinks recorded in the early 1970s, and Jobriath’s orchestration for “What a Pretty” is impressively threatening. Only a few songs, “Ooh La La” and “Sister Sue,” break free of the theatricality to stand on their own as glam-rock. There are many similarities to Jobriath’s debut here, but the overall result is more fragmented and contains few nods to radio-ready compositions. After promotional fiascos consumed Jobriath’s debut, there seemed to be no interest in commercial pretensions on what would be his swansong. Dropped by both his manager and label, he retreated from the music industry, reappearing a few years later as a lounge singer named “Cole Berlin,” and passing away largely unnoticed in 1983. With the reissue of his two Elektra albums, modern-day listeners can hear his music in place of his hype, and the music – particularly the debut album – is worth hearing. —hyperbolium

Ride “Nowhere” (1990)

At first listen, this album seemed simply good to average in my mind. Then, I found myself listening to this disc unfailingly for three straight days as the rush of spacey guitars and foggy vocals slowly burned their way into my psyche. While the album begins with the fairly straight-ahead “Seagull,” the rest of the tunes shimmy into a cascade of entrancing sound that completely (if not subliminally) sneak into the listener’s consciousness.

The dream-like elements are all in place: dense, rapturous, guitars, strategically placed and often delicate drums, tight rhythmic pulses, and distant, angelic vocals. Hypnotic in every sense, tracks such as “In a Different Place,” and “Vapour Trail” wash over you like a cool blue wave. Do yourself a favor and take this ride. —Erik