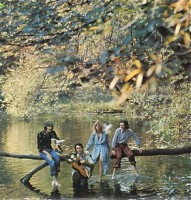

If you’re an Airplane fan, you want to give this one a try. Yes, this is the earliest album to use the “Jefferson Starship” name, but it’s not the first official Starship album, this is simply a Paul Kantner solo project in between Airplane albums (Volunteers, Bark) with an all-star cast of musicians helping out with the name Jefferson Starship (including several Airplane members like Grace Slick, Jack Casady, Joey Covington as well as three Dead members, Jerry Garcia, Bill Kreutzmann, and Mickey Hart, plus David Crosby and Graham Nash, and ex-Quicksilver Messenger member and future Airplane/Jefferson Starship member David Freiberg, plus Peter Kaukonen, Jorma’s brother). The Airplane at this point was in flux having just lost Marty Balin and Spencer Dryden, so this gave Kantner the idea for a solo project. Luckily the music has much more in common with the Airplane sound circa Volunteers, so if you’re fearing a precursor to the Red Octopus sound, don’t worry, Pete Sears and Craig Chaquico ain’t here! Not to mention no Papa John Creach. To me, Blows Against the Empire is one of the last great West Coast psych albums. 1970 was obviously difficult times for the counterculture, as it was pretty much on decline, no doubt helped by the Kent State shootings, so this album was basically about a bunch of hippies who hijack a starship to sail off to the stars because they no longer feel welcomed on Earth. The album was nominated for a sci-fi Hugo Award, but didn’t win. Strange that an album of recorded music would be nominated by such an award.

“The Baby Tree” is a silly little folk-number about babies growing on trees while “Let’s Go Together” sounds like a missing number from Volunteers. “A Child is Coming” is a nice pleasant acoustic number, which seemed to coincide to Grace Slick having a child that was to be born (China Kantner). “Hijack” is a totally wonderful epic number, where the band almost enters prog rock territory near the end with some wonderful use of piano. There’s a couple of short pieces that simulate the sounds of a starship taking off, oddly they remind me of such Krautrock groups of the time like Ash Ra Tempel or early Tangerine Dream. “Have You Seen the Stars Tonight” is the group exploring space rock with spacy psychedelic effects. It reminds me a tad of Crosby, Stills & Nash, but then Crosby and Nash do appear on this album. “Starship” sounds like how the Dead and Airplane might sound like if they teamed together as you hear a strong Dead/Airplane sound to this piece (not to mention Jerry Garcia giving his trademark lead guitars).

A totally wonderful, if often underrated album of West Coast psychedelia which I highly recommend. —Ben