Following a brief affair with heavy rock on the pair of Paris releases, Bob Welch puckers up and lands a solo soft rock triumph on French Kiss. While some of that guitar crunch remains, it and Welch’s trademark baked goods vocals are wrapped in silky disco strings and dance floor beats throughout the mesmerizing French Kiss. The LP finds Welch as a post-hippie playboy on the prowl through irrepressible entries like the alluring “Ebony Eyes,” “Hot Love, Cold World,” and the Fleetwood/McVie/Buckingham assisted infatuation of “Easy to Fall” and “Sentimental Lady,” originally cut for the Mac’s Bare Trees. Elsewhere the disco-rockin’ “Carolene,” funky “Outskirts,” vintage Welch space-drifter “Danchiva” and sunny Claifornia dreamin’ duo of “Lose my Heart” and “Lose Your Heart” only serve to solidify the album’s appeal – rare is the seventies softie that never dips in quality, all while delivering the lounge lizard magic in such spot-on fashion as on French Kiss. –Ben

Following a brief affair with heavy rock on the pair of Paris releases, Bob Welch puckers up and lands a solo soft rock triumph on French Kiss. While some of that guitar crunch remains, it and Welch’s trademark baked goods vocals are wrapped in silky disco strings and dance floor beats throughout the mesmerizing French Kiss. The LP finds Welch as a post-hippie playboy on the prowl through irrepressible entries like the alluring “Ebony Eyes,” “Hot Love, Cold World,” and the Fleetwood/McVie/Buckingham assisted infatuation of “Easy to Fall” and “Sentimental Lady,” originally cut for the Mac’s Bare Trees. Elsewhere the disco-rockin’ “Carolene,” funky “Outskirts,” vintage Welch space-drifter “Danchiva” and sunny Claifornia dreamin’ duo of “Lose my Heart” and “Lose Your Heart” only serve to solidify the album’s appeal – rare is the seventies softie that never dips in quality, all while delivering the lounge lizard magic in such spot-on fashion as on French Kiss. –Ben

Rock

Beyond the Gilded Palace:

A Guide to Country Rock’s Golden Age

Even though early rock and roll was deeply rooted in country music, the two were ideologically at odds from the start. This rift became more pronounced as the ’50s gave way to the ’60s, and by 1965 Nashville was more provincial than ever, seemingly impervious to the supernovas of musical activity in cities like London and LA. Nevertheless, rumblings of a sea change can be heard during this time period even in the music of Rock’s prime movers, the Beatles’ “Run For Your Life” on Rubber Soul just one example.

In 1966, less than a year after he had almost been booed offstage for playing an electric guitar at the Newport Folk Festival, Bob Dylan would travel to Nashville to cut a little record called Blonde On Blonde. Similarly, even on their early albums the Byrds and Buffalo Springfield wore their country influences on their sleeves, this mark of distinction becoming even more pronounced with each release. Something needed to give, and give it eventually did in the summer of 1968. Embracing traditional country & western (some argue to a fault), the Byrd’s landmark LP Sweetheart of the Rodeo announced the arrival of a new aesthetic. Released the following spring, Bob Dylan’s downhome Nashville Skyline upped the ante even more.

These records confused both the squares and the hippies when they came out, but not as much as when Gram Parsons and Chris Hillman defected from the Byrds to form the Flying Burrito Brothers. Parsons, most largely responsible for the Byrd’s dramatic switch to Country purism on “Sweetheart…”, needed a broader sonic canvas to explore his “Cosmic American Music”, and he would do just that on 1969′s The Gilded Palace of Sin. Its cover, depicting the long-haired Parsons in a marijuana leaf-patterned rhinestone suit, conveyed its mission statement almost as much as the music within. Unlike the Byrds’ and Dylan’s albums, The Gilded Palace of Sin took pieces from country and rock and reassembled them into something truly unique. Of the three releases in this “Country Rock Holy Trinity”, the Burrito’s album sold the most poorly, but its long-term impact exceeded that of its counterparts. Immediately after its release, musicians of all stripes took notice, and decades later the alt. country movement would be born when bands such as Uncle Tupelo and the Jayhawks returned to this well with a similar M.O. But the few years between the late ’60s and early ’70s represent what can only be called Country Rock’s Golden Age. Below are some more highlights:

1. Bradley’s Barn Beau Brummels (1968) This release by undervalued San Francisco folk rockers, which arrived in stores just a few short weeks after Sweetheart of the Rodeo, is in some ways more successful than its competition. Much of this can be attributed to Sal Valentino’s gritty vocals and the impeccable picking of some ace Nashville sessioneers.

1. Bradley’s Barn Beau Brummels (1968) This release by undervalued San Francisco folk rockers, which arrived in stores just a few short weeks after Sweetheart of the Rodeo, is in some ways more successful than its competition. Much of this can be attributed to Sal Valentino’s gritty vocals and the impeccable picking of some ace Nashville sessioneers.

2. Goose Creek Symphony Established 1970 (1970) On their debut album, this Arizona outfit conveys a laid-back and goofy stoner vibe, which somewhat belies its virtuosic musicianship. Its side two opener, “Talk About Goose Creek and Other Important Places”, is one of country rock’s great psychedelic rave-ups.

2. Goose Creek Symphony Established 1970 (1970) On their debut album, this Arizona outfit conveys a laid-back and goofy stoner vibe, which somewhat belies its virtuosic musicianship. Its side two opener, “Talk About Goose Creek and Other Important Places”, is one of country rock’s great psychedelic rave-ups.

3. Grateful Dead American Beauty (1970) Which Grateful Dead album most typifies country rock is open to debate; clearly, it’s a toss-up between Workingman’s Dead and their next album, American Beauty. But in the end the latter achieves this distinction, if only by a slim margin. Featuring Jerry Garcia’s sparkling pedal steel guitar and some of the band’s best ever harmonies, the Dead would never sound this great in the studio again.

3. Grateful Dead American Beauty (1970) Which Grateful Dead album most typifies country rock is open to debate; clearly, it’s a toss-up between Workingman’s Dead and their next album, American Beauty. But in the end the latter achieves this distinction, if only by a slim margin. Featuring Jerry Garcia’s sparkling pedal steel guitar and some of the band’s best ever harmonies, the Dead would never sound this great in the studio again.

4. Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen Lost in the Ozone (1971) Looking back almost as much as it looked forward, this raucous album introduced elements of rockabilly and boogie-woogie into the country rock mix. Commander Cody would record some more great albums, but this remains his definitive statement.

4. Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen Lost in the Ozone (1971) Looking back almost as much as it looked forward, this raucous album introduced elements of rockabilly and boogie-woogie into the country rock mix. Commander Cody would record some more great albums, but this remains his definitive statement.

5. Michael Nesmith And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’ (1972) The Monkees’ hippest member recorded some of the best music in the country rock canon. But this minimalist outing, which features a rendition of “Different Drum” that’s superior to Linda Ronstadt’s version, is a true standout.

5. Michael Nesmith And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’ (1972) The Monkees’ hippest member recorded some of the best music in the country rock canon. But this minimalist outing, which features a rendition of “Different Drum” that’s superior to Linda Ronstadt’s version, is a true standout.

Further listening: Across the pond, Americana made its mark in 60′s Britain as well. For an idea of what what Country sounds like when it’s melded with Yardbirdsy blues, check out The Country Sect by The Downliners Sect; its 1965 release date makes it a record that was truly ahead of its time. Ray Davies was also taking notes when it came to Country, and his obsessions with it are most successfully explored on the Kinks’ last great album, 1971′s Muswell Hillbillies. Brinsley Schwarz, a band that counted Nick Lowe as an original member, were major underachievers in their day, but their take on country would come to define another genre, pub rock. Their second LP, Despite it All, is a small masterpiece. – Richard P

Are we forgetting anyone? We’d love to hear your comments:

ZZ Top – Tejas (1977)

1977s Tejas is a transition album for Texas rockers ZZ Top. It is the beginning of their step away from the Blues Rock that had brought them fame and a lot of record sales and towards the 1980s Electronic Blues that would eventually make them a worldwide phenomenon. There is more of the former Blues Rock than the latter Electronica here though. Tejas is almost as good a ZZ Top’s masterpiece Deguello, but is held back by some weaker tracks, something Deguello didn’t suffer from. Still there are some amazing songs here, notable the blazing, yet tongue in cheek Arrested for Driving While Blind, the countrified and rollicking She’s a Heartbreaker, and the achingly beautiful Asleep in the Desert. Overall Tejas is an important part of ZZ Top’s discography, and a very good album. –Karl

1977s Tejas is a transition album for Texas rockers ZZ Top. It is the beginning of their step away from the Blues Rock that had brought them fame and a lot of record sales and towards the 1980s Electronic Blues that would eventually make them a worldwide phenomenon. There is more of the former Blues Rock than the latter Electronica here though. Tejas is almost as good a ZZ Top’s masterpiece Deguello, but is held back by some weaker tracks, something Deguello didn’t suffer from. Still there are some amazing songs here, notable the blazing, yet tongue in cheek Arrested for Driving While Blind, the countrified and rollicking She’s a Heartbreaker, and the achingly beautiful Asleep in the Desert. Overall Tejas is an important part of ZZ Top’s discography, and a very good album. –Karl

Van Morrison “Astral Weeks” (1968)

“If I ventured in the slipstream, between the viaducts of your dream…” and so opens the poetic dream masterpiece, Van Morrison’s “Astral Weeks.” It’s one of those monuments to human emotion that has the power to carry the weight of your life with it. The funny thing is, I really wasn’t feeling Van for the longest time, always shelving him away in the “mom-rock” bin. Then all of a sudden something hit me and quickly snowballed into the realization of his genius. With Astral I find the strength lies in the fact that, although the production is both classical and traditional in instrumentation, the record comes across as highly psychedelic from the mysticism of the arrangements. It’s similar in that way to the first few Leonard Cohen records or Townes Van Zandt’s “Our Mother the Mountain,” And for being such a contender among quality poetic-psyche LP’s, it’s easily available and usually pretty cheap, so there’s no reason why you can’t check it out. –Alex

“If I ventured in the slipstream, between the viaducts of your dream…” and so opens the poetic dream masterpiece, Van Morrison’s “Astral Weeks.” It’s one of those monuments to human emotion that has the power to carry the weight of your life with it. The funny thing is, I really wasn’t feeling Van for the longest time, always shelving him away in the “mom-rock” bin. Then all of a sudden something hit me and quickly snowballed into the realization of his genius. With Astral I find the strength lies in the fact that, although the production is both classical and traditional in instrumentation, the record comes across as highly psychedelic from the mysticism of the arrangements. It’s similar in that way to the first few Leonard Cohen records or Townes Van Zandt’s “Our Mother the Mountain,” And for being such a contender among quality poetic-psyche LP’s, it’s easily available and usually pretty cheap, so there’s no reason why you can’t check it out. –Alex

Fleetwood Mac “Tusk” (1979)

I believe that the true power in this world is love. There’s obviously a strong universal relation to the longing of the soul. I also believe that Fleetwood Mac just might be the best musical representation of love. I could probably write about any Mac record, making similar points, TUSK just happens to be living on my turntable at the moment. It’s not a perfect album by any means, but when you dive deep into this band, it all hits the spot. TUSK is the double-LP follow up to their multi-platinum break up monster, Rumors. Of course there’s no way Tusk could ever have been nearly as much of a commercial success, but that’s what’s nice about it for me, there’s at least one full-length records worth of killer pop “anti” hits that still satisfy the listener in the same way, beautiful vocal coloring over lindsey buckingham’s percussive strumming and driven home by that wonderful snare crack that mick fleetwood perfected in the pop years. Plus this seems to be the point where Buckingham really took over the production and, for lack of a better term, went insane. So the arrangements are wacky as hell at some points and he must have played at least 50 different stringed instruments on it, but what’s love without craziness? Give this a chance if you haven’t already. For lovers only. –Alex

I believe that the true power in this world is love. There’s obviously a strong universal relation to the longing of the soul. I also believe that Fleetwood Mac just might be the best musical representation of love. I could probably write about any Mac record, making similar points, TUSK just happens to be living on my turntable at the moment. It’s not a perfect album by any means, but when you dive deep into this band, it all hits the spot. TUSK is the double-LP follow up to their multi-platinum break up monster, Rumors. Of course there’s no way Tusk could ever have been nearly as much of a commercial success, but that’s what’s nice about it for me, there’s at least one full-length records worth of killer pop “anti” hits that still satisfy the listener in the same way, beautiful vocal coloring over lindsey buckingham’s percussive strumming and driven home by that wonderful snare crack that mick fleetwood perfected in the pop years. Plus this seems to be the point where Buckingham really took over the production and, for lack of a better term, went insane. So the arrangements are wacky as hell at some points and he must have played at least 50 different stringed instruments on it, but what’s love without craziness? Give this a chance if you haven’t already. For lovers only. –Alex

King Crimson “Red” (1974)

A caged beast of a record, and easily this group’s best, it strips away most of their obscurantist pretensions to serve up a guitar bass and drum assault that runs frequently into the red and is something to behold: Bruford’s drumming is jaw-dropping, while Fripp plays with a dark metallic intensity that suggests he’s one of rock’s wasted talents. I can even put up with John Wetton here, whose ferocious bass playing is more like a second (maybe third) lead instrument and whose singing has a kind of macho bravura that suits this music’s seething intensity. Still, the beast is caged. I’m always a little let down by the second side, which is what keeps Red from essentially essential status, with the wandering “Providence” (another crack at the improv-based excursions heard on the previous album) and the somewhat undercooked “Starless.” No, I’m not kidding: “Starless,” which many listeners seem to think is a masterpiece, could’ve used a little more work. I’m forever disappointed by the whole trajectory of this track, which at 12-some minutes would’ve benefited from a few more (the majestic ending should’ve been lengthier, to provide a kind of bookend equivalent to the sturm-und-drang of “Red;” it may be quibbling, but it’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to). So, instead of the Godzilla of prog-rock tracks, “Starless” is merely a woolly mammoth. This group never made the great record they should’ve made. This one’s the only one that comes close. And oh so close. –Will

A caged beast of a record, and easily this group’s best, it strips away most of their obscurantist pretensions to serve up a guitar bass and drum assault that runs frequently into the red and is something to behold: Bruford’s drumming is jaw-dropping, while Fripp plays with a dark metallic intensity that suggests he’s one of rock’s wasted talents. I can even put up with John Wetton here, whose ferocious bass playing is more like a second (maybe third) lead instrument and whose singing has a kind of macho bravura that suits this music’s seething intensity. Still, the beast is caged. I’m always a little let down by the second side, which is what keeps Red from essentially essential status, with the wandering “Providence” (another crack at the improv-based excursions heard on the previous album) and the somewhat undercooked “Starless.” No, I’m not kidding: “Starless,” which many listeners seem to think is a masterpiece, could’ve used a little more work. I’m forever disappointed by the whole trajectory of this track, which at 12-some minutes would’ve benefited from a few more (the majestic ending should’ve been lengthier, to provide a kind of bookend equivalent to the sturm-und-drang of “Red;” it may be quibbling, but it’s my party and I’ll cry if I want to). So, instead of the Godzilla of prog-rock tracks, “Starless” is merely a woolly mammoth. This group never made the great record they should’ve made. This one’s the only one that comes close. And oh so close. –Will

Tim Buckley “Starsailor” (1970)

Tim Buckley had already begun to alienate his folkie fanbase with “Lorca” a few months earlier– what the hell was up with this golden-voiced disciple of Fred Neil? Why would he release an album filled with meandering free jazz-like structures and vocal gymnastics that made it sound as though he was being disemboweled? Well, if they wuz bewildered by “Lorca,” “Starsailor” musta felt like a kick in the groin. Not only was it a continuation of the avant garde themes which in hindsight, he’d barely scratched, it was a full-on operetta revolving around the pit of anguish that burned in his guts; he also began to fully utilize the five and a half octave vocal range he had at his disposal.

Tim Buckley had already begun to alienate his folkie fanbase with “Lorca” a few months earlier– what the hell was up with this golden-voiced disciple of Fred Neil? Why would he release an album filled with meandering free jazz-like structures and vocal gymnastics that made it sound as though he was being disemboweled? Well, if they wuz bewildered by “Lorca,” “Starsailor” musta felt like a kick in the groin. Not only was it a continuation of the avant garde themes which in hindsight, he’d barely scratched, it was a full-on operetta revolving around the pit of anguish that burned in his guts; he also began to fully utilize the five and a half octave vocal range he had at his disposal.

I’m gonna hazard a guess that Buckley had been listening intently to Leon Thomas– particularly his work with Pharaoh Sanders on “Karma.” He liberally borrows Thomas’ conventional-croon-to-absurd-yodel on several tracks, most notably “Monterey,” a dissonant Voodoo Blues that conjures a vibe equal parts atavistic ritual and sleazy mating call. Bunk Gardner, late of the Mothers of Invention, provides some Ornette-esque sax squawk, further pushing the song into uncharted territory– at least for the early 1970’s zeitgeist. “Moulin Rouge” is a brief slice of Franco-Pop that coulda easily been recorded by Edith Piaf– I only mention it as it is one of the few cuts that provides a respite from the suffocating melancholy and bordering on psychedelic experimentation that makes up the rest of the LP. For instance, the ethereal title track is akin to smoking far too much DMT, only to discover that instead of encountering the promised elves hiding in the artificial netherworld, you find yourself surrounded by bloodthirsty, shapeless abominations far outside the realms of HP Lovecraft’s worst nightmares. Lee Underwood’s stellar guitar work also deserves a nod. His connection with Buckley borders on preternatural– be it the spare, mournful licks he uses to accompany Tim’s wounded wail on the oft-covered/butchered “Song to the Siren,” or the majestic, fleet-fingered riffs that double Buckley’s vocal on “Come Here Woman.”

If you’re new to the elder Buckley, this may not be the best place to start. I’d recommend “Dream Letter: Live in London” for virgins, as well as for fans of his offspring, a certain Jeff. –Jake P

Phil Manzanera/801 “801 Live” (1976)

Not your every day live album, 801 Live captures the supergroup featuring ex-Roxy Musicians Phil Manzanera and Brian Eno in one of their few performances. Featuring all the sonic detail, colorful guitar and synthesizer tones, and high-class musicianship you’d expect from such a lineup, another pleasant surprise here is the excellent recording, which almost sounds more like a studio album. A subtle, delicate style informs many of these performances, highlighting tracks from Eno and Manzanera’s early solo albums, the Quiet Sun album, and skewed reworkings of “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “You Really Got Me.” Brainy and electronic, but warm and human as well, 801 Live is an essential purchase for fans of the musicians involved, or seventies art-rock in general. –Ben

Not your every day live album, 801 Live captures the supergroup featuring ex-Roxy Musicians Phil Manzanera and Brian Eno in one of their few performances. Featuring all the sonic detail, colorful guitar and synthesizer tones, and high-class musicianship you’d expect from such a lineup, another pleasant surprise here is the excellent recording, which almost sounds more like a studio album. A subtle, delicate style informs many of these performances, highlighting tracks from Eno and Manzanera’s early solo albums, the Quiet Sun album, and skewed reworkings of “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “You Really Got Me.” Brainy and electronic, but warm and human as well, 801 Live is an essential purchase for fans of the musicians involved, or seventies art-rock in general. –Ben

Joni Mitchell “The Hissing of Summer Lawns” (1975)

And so, the dazzling beauty of Court and Spark carries on with The Hissing of Summer Lawns. Musically, it continues in a similar vein – an all-star lineup effortlessly shifting between Pop, Folk and Jazz, playing rich, multi-layered arrangements which never overpower Joni, whose main concern is always the song and its words. The lyrics have become more intimate, more melancholic on The Hissing of Summer Lawns and so has the music. Again, one or two songs don’t meet my undivided approval (Shadows and Light and The Jungle Line, even though the song marks the beginning of a lasting Pop format, the attempt to create a multicultural world music, ten years before Peter Gabriel, Sting and others), but the rest is again of celestial beauty. Even Joni, who would go on to record important albums until today, wasn’t able to match the artistic consistency and beauty of Court And Spark and The Hissing of Summer Lawns until many years later, with Turbulent Indigo and Travelogue. –Yofriend

And so, the dazzling beauty of Court and Spark carries on with The Hissing of Summer Lawns. Musically, it continues in a similar vein – an all-star lineup effortlessly shifting between Pop, Folk and Jazz, playing rich, multi-layered arrangements which never overpower Joni, whose main concern is always the song and its words. The lyrics have become more intimate, more melancholic on The Hissing of Summer Lawns and so has the music. Again, one or two songs don’t meet my undivided approval (Shadows and Light and The Jungle Line, even though the song marks the beginning of a lasting Pop format, the attempt to create a multicultural world music, ten years before Peter Gabriel, Sting and others), but the rest is again of celestial beauty. Even Joni, who would go on to record important albums until today, wasn’t able to match the artistic consistency and beauty of Court And Spark and The Hissing of Summer Lawns until many years later, with Turbulent Indigo and Travelogue. –Yofriend

The Velvet Underground “1969: The Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed” (1974)

“Good evening, we’re the Velvet Underground…” It’s a far cry from another intro uttered that same year: “Ladies and gentleman, the greatest rock and roll band in the world…” Lou Reed’s intro is obviously more understated and, coming from a notoriously prickly New Yorker, surprisingly cordial. And it goes on for awhile… After asking the audience if they would prefer a one-long-set or two-set performance, we get a recap of a Dallas Cowboys game. Almost a full minute and a half has passed when, out of nowhere, Reed casually states, “This is a song called I’m Waiting for My Man”. The band then wastes no time locking into an historic, rock-solid groove.

“Good evening, we’re the Velvet Underground…” It’s a far cry from another intro uttered that same year: “Ladies and gentleman, the greatest rock and roll band in the world…” Lou Reed’s intro is obviously more understated and, coming from a notoriously prickly New Yorker, surprisingly cordial. And it goes on for awhile… After asking the audience if they would prefer a one-long-set or two-set performance, we get a recap of a Dallas Cowboys game. Almost a full minute and a half has passed when, out of nowhere, Reed casually states, “This is a song called I’m Waiting for My Man”. The band then wastes no time locking into an historic, rock-solid groove.

1969: The Velvet Underground Live with Lou Reed has always been a VU fan favorite, but it’s overshadowed by the band’s iconic studio catalog. Misguided marketing and lame packaging are also to blame for its somewhat limited cult status. Released in 1974, during the most lucrative period of Lou Reed’s solo career, Mercury’s insistence on using his name in the title implied that other members of the VU were little more than his backing band, which couldn’t be further from the truth. The inner gatefold spread is also misleading, depicting an earlier and different (in both sound and appearance) incarnation of the band. Finally there’s the cover itself, which, in the immortal words of Patti Smith, “eats shit”. Despite this indifferent misrepresentation, this record is the first and last word in any discussion about the Velvet Underground as a live act. Almost all of the band’s classics are here, given new life—sometimes even bettered—by Reed’s remarkably expressive vocals (one pines for the days when he actually sang), Sterling Morrison’s precision guitar work, Mo Tucker’s majestically simplistic drumming, and the melodic bass-playing of the most under-appreciated VU member, Doug Yule. Surprisingly large amounts of live VU performances were recorded, but this collection—the bulk of which was culled from a multi-night engagement at a tiny club in Dallas—has the best sound quality of any that have survived. It’s a different sound than the sharp and crackly production of the 1967 “Banana” LP: bluesier, and with a bottom that rattles the windows and shakes the floors. It’s the sound of a band that’s been honing its craft in divey clubs and ballrooms across the US for over a year, and which, during the last few months of the ’60s, delivers the best live rock and roll show on either side of the Mississippi. –Richard P

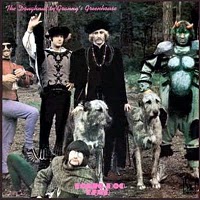

The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band “The Doughnut in Granny’s Greenhouse” (1968)

The great lost psychedelic album. On their second album the Bonzos knock off the trad jazz parodies and pair their surreal lyrics and wild imaginations with rock music to match. Neil Innes still gets to sing the catchiest songs — “Beautiful Zelda”, for instance, examines the perils of dating a space alien — but Vivian Stanshall beats him with what could be the band’s mission statement, “My Pink Half Of The Drainpipe”. Plus there’s the amazing Love parody “We Are Normal” (“and we dig Bert Weedon!”). The summit, though, is the too awesome for words “Rhinocratic Oaths”, which, with its cheery narration (“You should get out more, Percy, or you’ll start acting like a dog, ha ha … He was later arrested near a lamp-post”) reveals the Bonzo’s ultimate truth: that there is nothing so lunatic as what passes for everyday life. (Hey, that Dada/Doo-Dah wasn’t in their name for nothing.) If you have any spark of imagination or individuality, you must get this record. –Brad

The great lost psychedelic album. On their second album the Bonzos knock off the trad jazz parodies and pair their surreal lyrics and wild imaginations with rock music to match. Neil Innes still gets to sing the catchiest songs — “Beautiful Zelda”, for instance, examines the perils of dating a space alien — but Vivian Stanshall beats him with what could be the band’s mission statement, “My Pink Half Of The Drainpipe”. Plus there’s the amazing Love parody “We Are Normal” (“and we dig Bert Weedon!”). The summit, though, is the too awesome for words “Rhinocratic Oaths”, which, with its cheery narration (“You should get out more, Percy, or you’ll start acting like a dog, ha ha … He was later arrested near a lamp-post”) reveals the Bonzo’s ultimate truth: that there is nothing so lunatic as what passes for everyday life. (Hey, that Dada/Doo-Dah wasn’t in their name for nothing.) If you have any spark of imagination or individuality, you must get this record. –Brad

J.J. Cale “Troubadour” (1976)

J.J. Cale’s fourth album Troubadour is a mixed stew of everything from country, jazz, arena rock, blues, folk to funk; and that’s just in the first song. He manages to whisper like Nick Drake, growl like John Lee Hooker and wine like Dylan…did I mention he’s an extremely adept guitar player as well? Cale’s songs have been covered by many artists, the most famous being “Cocaine” by Eric Clapton, but here we have the original; stripped down, but somehow fuller, with funky jabs and clumsy power chords. There’s also some simple love songs as well, “Hey Baby” never gets too corny with jazzy horn phrases intertwining with country style chicken-pickin.’ “Travelin’ Light” is an intense study of the driving song with guitars and vibes throughout, pulsing like highway lines in the corner of your eye. This record is about the groove, while brilliant arrangements and clever instrumentation provide the texture, making everything unclassifiable. –ECM Tim

J.J. Cale’s fourth album Troubadour is a mixed stew of everything from country, jazz, arena rock, blues, folk to funk; and that’s just in the first song. He manages to whisper like Nick Drake, growl like John Lee Hooker and wine like Dylan…did I mention he’s an extremely adept guitar player as well? Cale’s songs have been covered by many artists, the most famous being “Cocaine” by Eric Clapton, but here we have the original; stripped down, but somehow fuller, with funky jabs and clumsy power chords. There’s also some simple love songs as well, “Hey Baby” never gets too corny with jazzy horn phrases intertwining with country style chicken-pickin.’ “Travelin’ Light” is an intense study of the driving song with guitars and vibes throughout, pulsing like highway lines in the corner of your eye. This record is about the groove, while brilliant arrangements and clever instrumentation provide the texture, making everything unclassifiable. –ECM Tim